by Laura Villareal

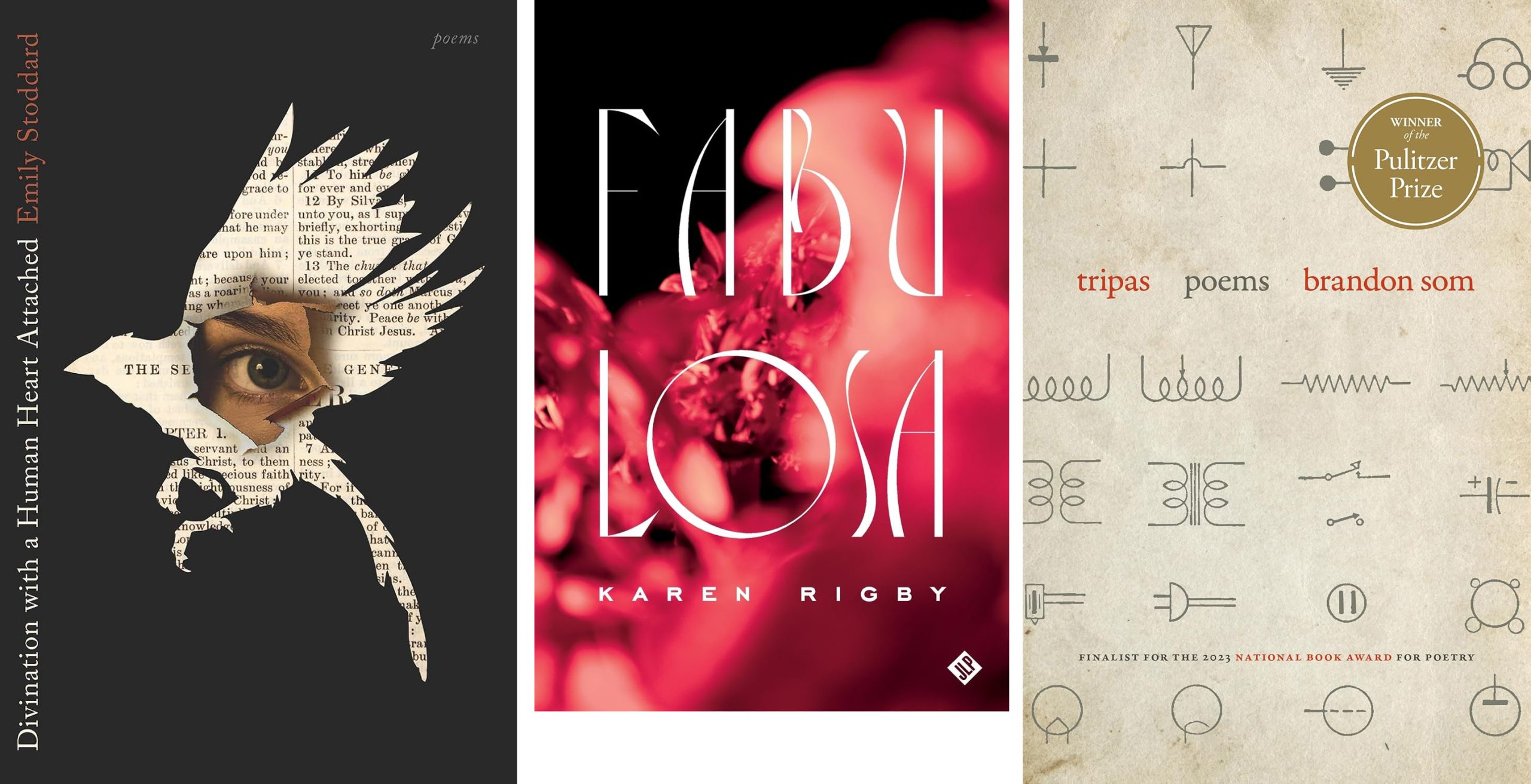

Divination With a Human Heart Attached, by Emily Stoddard. Game Over Books, 72 pp., $18.

Fabulosa by Karen Rigby. Jackleg Press, 62 pp., $18.

Tripas by Brandon Som. The University of Georgia Press, 93 pp., $19.95.

I’ve been a bit restless in my reading these past few years. I’ve found myself increasingly interested in poets who build precise language systems, especially if they’re able to take familiar language and examine it in a way that illuminates the peculiarity of its particularity. There’s something about being reminded that there’s still more to know about my daily life—that there are surprises, connections, and relationships between words I hadn’t considered. There’s so much in my immediate world I can’t readily name. If you are like me you may end up Googling things like “anatomy of an orange,” “life cycle of a Mexican Bean Beetle,” or “parts of door lockset” in order to speak precisely and find words like “strike plate,” “pupa,” or “flavedo.” Modernity has made much in our world convenient, easy, thought-free. Some language seems to be lost due to the waning of specific jobs in the modern world, like tailoring. The three collections I’ve chosen satisfy my desire for specificity. They lean into the peculiar particular and press on the pulse of language that reminds us that there is more wonder to be found in our world.

I

I went to Catholic school from elementary school through high school. In elementary school we went to the chapel to attend Adoration once a month. We spent an hour of silence in which we prayed the rosary, read the Bible, and squirmed in the absence of chatter, as children inevitably do. This quiet time of prayer and reflection was likely more for our teacher’s sanity than our immortal souls, but I think it taught me to be comfortable in silence. Adoration, otherwise known as Eucharistic Adoration, is a worship ritual conducted in the presence of the Eucharist displayed in the monstrance; it’s done as a way to view and worship Christ embodied in the Eucharistic Host. A Host is a thin wafer, the alleged body of Christ. The monstrance is a golden vessel, often shaped like sunlight or a celestial burst placed on the altar. Monstrance derives from the Latin monstrare meaning “to show.” As I remember the language of Catholic tradition, the words feel strange and mystical. I’m so far removed from religion that the language is peculiar and particular, but what was once ordinary in my childhood is now aflame with renewed curiosity. For those of us who were raised in a religion, our poems often continue to house iconography, fragments of prayers, and pieces of ritual. It’s inescapable.

Such is the case with Emily Stoddard’s debut Divination with a Human Heart Attached, a book that summons a natural world entangled in mysticism, religion, and saints. Ordinary images transform into the extraordinary in Stoddard’s well-crafted poems.The book opens with the lines “The trouble is / everything calls to me.” And it’s evident that Stoddard finds beckoning strangeness in everything. In the first poem, “More & More,” she elaborates:

The wolf is a recurring motif, perhaps a nod to biblical references like Matthew 10:16, which says “Behold, I am sending you out as sheep in the midst of wolves, so be wise as serpents and innocent as doves.” The idea of not turning away echoes back to the book’s epigraph, “They say the magpie refused shelter / in the ark, chose to stay outside / and watch / the waters rise.”

Both the wolf and the magpie return in “Magpie Says”. Written after Sharon Olds’ poem “Satan Says,” much of the poem mirrors Olds’ syntax and structure. Magpies, like many birds, have a lot of superstitions and lore surrounding them. “One for Sorrow, Two for Joy” takes its title from the first two lines of an old nursery rhyme about magpies, and Stoddard titles other poems after the lines that follow, up to the last: “Thirteen beware it’s the devil himself.” Though there is no consensus on whether magpies are good or ill fortune, the epigraph of section two and section three in the booksuggest the speakers’ leanings on the matter. The second reads, “They say the magpie was the only bird / who chose not to sing or dress / in mourning / at the crucifixion” and the third says, “They say the devil left a drop of blood under / the magpie’s tongue. They say the magpie has a long / memory for faces, remembers the good ones apart / from the bad, can recognize her own / in the mirror.” It’s clever how the poet has used the section epigraphs as an embedded narrative. A thread that runs through the book is the story under the story which we see unfold in several poems including “Magpie Says.”

Though the syntax and structure of Stoddard’s poem mirrors Olds’ what is beneath feels tied to the church rather than the family. Stoddard writes,

The christogram’s X pinning the speaker and the fact that she’s “locked in a little oak confessional” seem to suggest the speaker feels trapped within religion. At the same time, Stoddard evokes the confessional recitation “forgive me, it has been so long since my last confession / and I do not know how to begin.” Then the magpie provides unsettling language for the speaker to confess and break out. It’s almost as if the magpie is the speaker’s unconscious, forcing the speaker to give name to the tension within them.

What’s most clear is that the speaker feels as though “the church is a broken body” and “the brother is a wolf in a tabernacle.” A tabernacle is the box that houses the Eucharist, which is believed to house the spirit of Jesus, so the fact that the brother (it’s uncertain whether familial or religious brother) is a wolf inside means there has been a critical disruption or invasion into the sacred space. These ideas are reinforced later in the poem:

Religious abuse and trauma are more evident in these lines, most notably in “And the church closes / tight her eyes.” The magpie up close to the speaker’s face, allowing her to see better, and resembling grief is a powerful gesture towards confronting what has happened. Like the magpie in the first epigraph who watches the flood waters rise, the speaker of “Magpie Says” bears witness.

“Here, amen is not amen,” the poem that closes Divination with a Human Heart Attached, gorgeously affirms the necessity of witness:

Aside from fragments of religion like those found in “Magpie Says,” Stoddard’s poems frequently explore plant life. One of the recurring plants is Datura, a poisonous and psychoactive plant, which goes by many names including devil’s snare, jimson weed, and thorn-apple. In folklore, Datura was believed to be used by witches for brews and medicines. There’s a fine line between religion and superstition—both depend on belief in the divine and the mystic, defined by ritual, and uplifted by the stories we tell about them.

In “I might have been a botanist,” the speaker considers what would have happened if they had been allowed to learn about “the reproductive / habits of flora and fauna” rather than being “sent to the chapel / to kneel.” The poem leans into scientific names for plant parts: “anther,” “stigma,” “filament,” “xylem,” and “phloem.” The specificity enriches the poem, showing how knowledge makes “the forbidden more ripe.” The speaker learns to distinguish the “purple stalk” of the invasive, non-native loosestrife, and rips it out before it chokes the native and medicinal bee balm, ironweed, and boneset.

Divination with a Human Heart Attached is an outstanding and rich debut. Stoddard’s attention to storytelling, order, and symbology results in a book that gains new meaning and depth with every reading. With a debut like this, Stoddard is likely a poet whose work will be celebrated for many years to come.

II

As the luxurious title Fabulosa suggests, Karen Rigby’s second poetry collection entices and entertains in its cinematic lyricism. The poems feel like old Hollywood, adorned in satin and suede. They’re like watching the Met Gala’s red carpet, never knowing what delight will appear after the last. The opening poem, “Why My Poems Arrive Wearing Black Gloves,” is a particularly confident ars poetica. Rigby writes:

A poem recounting the critique of her first book in a collection that doubles down on that book’s aesthetic is a provocative choice. Warranted self-assuredness in the writing world is rare, but Rigby knows her poems aren’t just glitz and it’s admirable to see her lean into her singular aesthetic. Rigby’s voice is beguiling, a bit hypnotic in its playful extravagance. Notably here, by her turning the camera on herself and then on the reader she clarifies our relationship to the work. It’s a clever invitation to not just stay on the surface of the poem, but to enter into the frame, which she further emphasizes in the lines “no one’s reading / this poem to picture my life.” It’s true, we read poems because we hope we find something to mirror back ourselves and to surprise or console us. “A poem is a diamond heist” and that feels true in Fabulosa because it seems that Rigby’s poems can only shine and shine.

Fashion and the language of tailoring play a significant role in the collection, adding to the opulence of the book’s image system. In an era of fast fashion, the language of tailoring has been lost as most people opt for ready-to-wear pieces over the bespoke and tailored garments of previous eras. Companies now even tout washable silk, a fabric that was unthinkable to machine-wash in years past. For the most part, apart from clothes enthusiasts, people may be able to distinguish quality by feel but are likely not able to name various weaves of cotton: poplin, end-on-end, twill, oxford, and so on. Capitalism estranges us from the process that create in the product. And even so, there is a resurgence of interest in clothes, particularly menswear. Notable fashion writer Derek Guy, who tweets fashion critiques of celebrity and politician’s attire, and culture writer W. David Marx have gained mainstream notoriety. I like to joke that the second-hand menswear market is singlehandedly keeping eBay afloat, but there are plenty of other second-hand clothing websites like Grailed and Marrkt that monopolize on our desire for designer clothes. Christian Dior imparted the following wisdom in his book The Little Dictionary of Fashion: A Guide to Dress Sense for Every Woman, “Don’t buy much but make sure that what you buy is good.” This is all to contextualize what makes Rigby’s linguistic encapsulation of language and fashion so irresistible.

In “The Bar Suit” Rigby revels in the language of design:

The famous “Bar” Suit was part of Christian Dior’s “New Look” collection which he launched after World War II in 1947. The iconic jacket is so beloved that it has been reinvented each season ever since. The highly feminine “wasp-waist” that Rigby describes as “silk civility a flag for romance” was truly that—a signal of the war’s end the beginning of clothes made merely for beauty’s sake— after years of structured, utilitarian, masculine clothes. Rigby delights in the “boning and yardage,” the “study of minimalist color,” and the styling of the outfit completed by “luxe hat and heels.” Her appreciation of the art innate in design combined with the specific details of the “Bar” Suit evoke the joy of the tactile. The scratch and softness of wool. The rigidity of boning contrasting with the flexibility of the cloth around it.

The poem then turns, as all good ekphrastic poems do, to something at the poem’s core. “The Bar Suit” continues,

The tension from contrasting manmade beauty like that of the “Bar” Suit and acknowledging the likelihood of manmade disaster as symbolized by the Doomsday Clock creates an unnerving undercurrent. The Doomsday Clock is only ever reset when there is a significant potential for global catastrophe like nuclear war, climate change, bioterrorism, biological threats, or other existential threats. At the time of writing this review, the Doomsday Clock is currently set at 90 seconds from midnight. The poem shifts again to the future’s arrival, forcing us to consider the denialism around us. Rigby locates the implicit metaphor within these two historical events, but leaves us to ruminate over the meaning as we consider questions like: Who is the magician’s wife? What does the magician make disappear? And why does she insist “it’s nothing?”

This is a classic Rigby ending. Her poems provide metaphors for us to ruminate in (sometimes offering up questions with no answers). Too often poets fall into the trap of didacticism as they close their poems, but Rigby skillfully avoids it throughout this collection. It’s clear that she has confidence not only in the strength of her writing, but also trust in her readers to locate meaning.

How rare to witness a poetry collection with this much swagger— Fabulosa deserves an encore. Cheers to more deliciously aesthetic, astonishingly confident poetry books from Karen Rigby.

III

Brandon Som opens his Pulitzer Prize winning book Tripas with “Teléfono Roto,” which evokes the legendary Mexican folk figure La Llorona:

According to the legend, La Llorona drowned her own children and now waits near bodies of water at night, wailing in her grief, so that she can drown any children who wander alone. As with most folklore, bits of the story often change when retold, but the warning stays the same. Many Latinx poets like Som continue to remake, remix, and retell the story of La Llorona. Folktales are our first warning about the dangers of the world; perhaps we turn back to them as a source of peculiar, culturally specific comfort.

Like folktales, dichos are proverbs that help us navigate the world. For example: camarón que se duerme, se lo lleva la corriente or the sleeping shrimp gets carried away by the current imparts the wisdom that we must stay attentive. In “Teléfono Roto” Som cleverly contrasts early communication like chisme (gossip), dichos (sayings/proverbs), and folktales with our current and most popular form of communication, cellphones.

The poem continues,

Creer means to believe and crear means to create. Som’s consideration of the closeness of these words and their “similar wiring” underscores how what we create and believe can be the same at their core. In fact, this is one of the crowning achievements of Tripas.

La Llorona is both nurturer and murderer. Her story is meant to scare us into good behavior, but as adults we continue to see her in different situations. For example, when we create solutions to modern problems that result in the destruction of the environment or detrimental health issues for workers or people living in surrounding areas, her wailing becomes our wailing in another place or time.

In Som’s poem, she’s pollution:

The jobs at the Motorola plant provided money for numerous families, but were also poisoning those in the surrounding area. Most workers likely didn’t think anything of the chemicals they used, trusting that the company they worked for would dispose of them responsibly. The turn of the poem cleverly weaves the familial history and the folklore.

The “game of telephone” reference primes readers for how language leaps and moves throughout the book. In Tripas, Som’s poems are tightly tuned to linguistic resonances, illuminating how words sound close (or are close) in their roots. He finds lyrical bridges which unify his Chinese American and Mexican American background—truly one of the most impressive and rightfully celebrated aspects of his work.

Cadence and the use of sound devices like assonance and consonance are expertly employed here as well as in other poems in Tripas. Even visually, the placement of “dice” above “dictates” above “translates” forces the consideration of the words and their similarities. The smooth glide from “wires” to “rewires” for the wonderful consonance of “rosary” and “Rosario” proves Som’s careful artistry.

Som’s poem continues its play in image and sound,

Here Som bridges languages through sound and image. There’s so much to unpack in these seven lines; the layers are rich and alive. Notably, “My dark moles, she says are lunares” triggers an irresistible sequence of imagery related to the celestial, because it’s too easy to locate lunar within the Spanish word for moles. The poem then shifts to a visual character for electricity電 and its appearance. Som writes, “I see lasso & chain link in the componentry” and it’s hard not to see what he describes when you look at the character. The character is a logogram—a symbol to represent a unit of language rather than a phonetic rendering. Switching between reading and writing using characters and the Latin phonetic alphabet has clearly enriched Som’s exploration of what is located at the heart of language, considering not only what it sounds like, but also what it looks like.

Som finds his way back to family and their labor when he writes: “an analemma tracing dagongmei & ensambladoras / from rural town to city factory,” nodding to the Chinese migrant worker women (dagongmei) and women assembly workers (ensambladoras). The poem continues to pay homage to his family’s work later in the poem where he writes:

The passage illustrates how factory work often came home with the workers and became a family project. The “oír origins” and the “echo in the hecho” are crucial to understanding Tripas. Oír, meaning to hear or to listen, and hecho, meaning made, affirm that listening and making are at the root of Som’s heritage and his work as a poet.

The importance of oír returns in the book’s long final sequence titled “Novena,” a series of nine ten-line stanzas each on their own page, perhaps representing the nine days of prayer in a Novena and the ten beads in a decade of the rosary. Som writes:

“The ear’s yearning,” “oír in memoir,” “a necklace of mnemonics” are all ways of saying the same thing— that language and names are ways to not forget.

Laura Villareal is a poet and book critic. Her debut poetry collection, Girl’s Guide to Leaving (University of Wisconsin Press 2022), was awarded Texas Institute of Letters’ John A. Robert Johnson Award for a First Book of Poetry and the Writers’ League of Texas Book Award for Poetry. She is currently an associate with Letras Latinas, the literary initiative at the University of Notre Dame’s Institute for Latino Studies. Villareal is a West Branch contributing editor.