A Better Place Is Hard To Find, by Aaron Fagan. The Song Cave 84 pp., $17.95

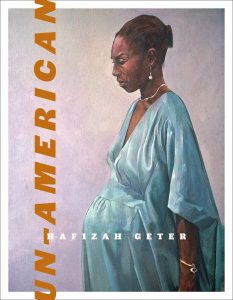

Un-American, by Hafizah Geter, Wesleyan University Press, 104 pp., $10.78.

Blizzard, by Henri Cole. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 80 pp. $24.

One of my favorite short stories is “Bullet in the Brain” by Tobias Wolff, in which Anders, a jaded book critic, gets shot in the head after laughing a little too hard at a bank robber’s thoroughly unoriginal dialogue. The point, in a sense, is that artists are not the only ones at risk of mistaking their work for their life. In another sense, though, Wolff makes clear that Anders the critic endured a spiritual death long before his physical one, and all the acid of his reviews pointed to the slow erosion of his soul. The tragedy of the story is thus the critic’s fall from wonder to a deadly cynicism—which is, one fears, a professional hazard. Indeed, while a critic requires certain tools to ply his trade—an incisive eye, a measured confidence of opinion, even a slight (slight!) fondness for his aesthetic prejudices—if he isn’t careful, he might one day begin to use all those tools like hammers. Which is to say, it’s easy to ask whether a book needs to be read, but much harder to ask whether it needs to be written. A poet risks disclosing their hopes, fears, and obsessions in their poems—that is, the depth or shallowness of their soul. All a critic can hope for, on the other hand, is not to expose himself as a man lacking one. The three books under review share in nothing other than being published within the past year in the United States. This was, in fact, the largest challenge in thinking about them all—their variousness. As a critic, I find it far easier to think of connections, themes, and common ground on which a review can rest; but in the course of writing about these very different collections, what sustained me was each poet’s search for a form of expression that suited their experience best, a private language they could claim as their own. So although these books achieve, to my mind, varying degrees of success between them, each reminded me in their own way that a human wrote these poems—that a human needed to write these poems. That, after all, is the only way a critic can keep his soul alive: by finding the reasons a book needed to be written.

I

Aaron Fagan’s third full-length collection, A Better Place is Hard to Find, is a slippery book. Such a texture is usually a virtue for water slides and even for some poets—think, for instance, of James Schuyler’s nimble long poems where sound is the only surface to grab onto. Many of Fagan’s poems, however, are more reminiscent of Teflon:

To cram strippers, heroin, serial killers, the collected poems of John Ashbery, and Stanley Kubrick into a scant eleven lines as the poem speeds to its conclusion is, I admit, a certain kind of accomplishment. Fagan has clearly borrowed heavily from Ashbery’s technical toolbox—the interest in contrasting high and low culture, the mixture of dictions, those self-reflexive glances cast toward the poetic process, the highly associative yet still vaguely narrative mode of the writing. All of these are strengths. Unfortunately, Fagan took less of Ashbery’s impeccable sense of timing or humor, and the poems—as in the lines above—often race breathlessly down the page, providing little purchase for the mind on the slick veneer of so much culture.

Fagan’s own mind is always furiously ruminating about mythology, or philosophy, or literature, love, physics, music, the meaning of labor. Surely one could get the sense while reading A Better Place that poems are more than anything little thinking boxes to be filled with interesting ideas, like a brainy freshman’s composition essay—even if the ideas don’t make particularly interesting poetry:

These lines are excerpted from the poem “Arrow of Time,” which takes its title from a physics concept proposing that time is asymmetrical—meaning, to state it roughly, that time appears to possess a direction: the past irreversibly behind us, the future blankly ahead. It’s a concept ripe for poetic inquiry—which is, I think, the source of my frustration with this book. Though I do truly feel richer after learning about Häxan, or refreshing myself on the myth of Tantalus, or working to understand what the asymmetry of time really means, again and again the poems seem able only to point to their ideas from a far distance. The result is a poem like “Arrow of Time,” where abstraction is layered on top of abstraction until its original brilliance, its initial spark, dims to the dead light of stars, a ghost platitude.

And yet, it would be unjust if I didn’t mention the ending of “The Deluge,” the final poem of A Better Place Is Hard to Find:

This writing is the best and most moving of the entire book. Here, the form finally exerts enough pressure on the language to remind the reader that poems most effectively interrogate experience by enacting it. I love the piercing immediacy of that enjambment, “joy rips me / Asunder,” as well as the tonal tension between joy, astonishment, and ennui, all of it handled so subtly and in such a short space. But most of all I’m grateful for the emotional clarity of these lines, where grief acts as a ballast for Fagan’s penchant to over-intellectualize.

I don’t mean that the poem, an elegy for the poet’s father, is perfect: earlier, the speaker with a quiet pathos tells us, “What my father / Knew, he practiced in silence,” only to add, “He / Was a rendition dissolved from order,” a sentiment so confounding that I honestly have no idea what it’s even suggesting. This is, in many ways, representative of Fagan—moments of near-beauty muddled by impenetrable profundities. Yet in light of “The Deluge,” the other poems in the collection acquire a certain coherence and raison d’être, shaped as they are by death. In efforts like “Eternal Return,” “Three Kinds of Everything,” or “At Poodle’s Core,” one can hear in their stark music an unmistakable urgency, even in their convoluted arguments:

That the emotional stakes of A Better Place Is Hard to Find emerge in such a retroactive and almost accidental fashion leaves me feeling ambivalent: I don’t want to wait until the final stanza to discover why a collection was written. Poetry should surprise, but not necessarily like the answer key at the back of a textbook does. On the other hand, I’m tempted to say that perhaps the poems fight against themselves because the poet was unclear about what he was getting at, even if it was still essential that he get at it. In other words, one might surmise, reading this book, that a poem’s need to exist outweighs its need to mean. In an interview given to Huck Magazine before A Better Place Is Hard to Find was published, Fagan practically throws up his hands at the specter of meaning: “That could be taken as a way of saying my poems are ‘full of nothing,’ which is fine,” he says. “I like the idea of saying ‘nothing’ in a beautiful and horrifying way.” Fagan, it seems, wants to believe that the way something is said is separate from what it’s saying. Such a conviction conveniently places the full burden of interpretation—and, if you like, meaning-making—onto the reader, while the poet shrugs and says “I’m just throwing out ideas.” It’s a nice deal, until the reader starts to wonder if he’s asked more from the poems than the poet did. At which point he stops trying to make sense of them at all, and closes the book.

II

Un-American, Hafizah Geter’s debut collection published by Wesleyan University Press, is beautiful as an artifact alone. Take the cover art, a portrait titled Nine Months—painted by the poet’s father, it depicts the poet’s mother who stands in profile wearing a cerulean dress, the light concentrated most heavily on her pregnant belly. An entire drama is sketched into the book before the first page is turned. Then the collection’s opening poem, “The Pledge,” expands and sharpens the themes the artwork suggests:

In a true display of skill, the poet immediately introduces Un-American’s central cast and quickly moves on to map the book’s setting, spanning between the United States and Nigeria, from “Zaria to Boston,” as well as Akron, Ohio, and the American South. She outlines the themes the poems will explore—inter-continental migration and identity, an intergenerational passion for art, the additions and losses a family sustains. Even the predominant tone of the poems to follow is hinted at, if not settled on, by the final lines of “The Pledge”: “Our bondage stretches / our ghosts in all directions trying to out-pick the rot / America has grown in our throats.” One enters this book feeling that the poet knows exactly what she wants to do.

Every decision Geter makes in Un-American seems aimed at the advancement of the collection as a whole. This would explain the manner of her poems, which usually examine the book’s central subject—the speaker’s family—through composite sketches; the speaker’s mother, father, and sister are approached multiple times from multiple angles, a method more prismatic than comprehensive. Thus, the poems require each other not only to accrete meaning, but also to develop and provide context. In “Salah,” we learn that the speaker’s relationship with her sister is strained (“my sister’s teeth are slats / on the broken bridge between us”). And although the reason for the estrangement is merely implied, it likely has something to do with the sister’s husband, his “stain / growing darker and darker.” Later on, “My Brother-in-Law Recites the Takbir” more specifically describes the shape of this marriage:

The brother-in-law’s shadow in the bedsheets here mirrors and modifies his earlier depiction as a darkening stain in “Salah,” and he therefore inhabits the poems both as a blemish and an absence. This is the chief pleasure of such a self-consciously interconnected collection: how the importance of an image or character is at once added to and revised the more one reads. (This accretion of history—is there a better metaphor for family life?) But despite the great care Geter takes to ensure the poems coalesce into a coherent, thought-out book, one can’t help wishing that she had paid just a little more attention—on a poem-by-poem basis, that is. As opposed to Aaron Fagan, Geter’s poems tend to achieve a visceral emotional response, even if the language itself, and the imagery in particular, is imprecise. When the speaker says her sister “deciphers” her pregnant belly across the bedsheets, for example, I can intuit the logic, the tie to the braille metaphor which embodies the brother-in-law’s inscrutable disappearances. Yet I can’t see what occurs in these lines: the verb functions solely on a figurative level, and obfuscates the literal.

This inexactness, for the most part small in scale, is nevertheless significant. In “How to Saw a Man in Half,” the speaker kneels over her father, “sopping his blood up / in fistfuls,” as though her hands were absorbent. In “Visiting Prophets,” the speaker visits Nigeria and drives past a group of armed guards “barely old enough to be lovers” who are “forgetting / the weight of their weapons, forgetting / our mothers have died / the same way,” though the shared cause of death between mothers remains unhelpfully ambiguous. Does the speaker mean gun violence, or the fatal brain aneurysm her mother succumbs to in “Naming Ceremony”? Does she, switching to an allegorical register, refer to the burden of living outside the country where one feels most at home? It’s a testament to Geter’s talent that each instance usually serves a discernable purpose—such as expressing a simultaneous sense of tenderness and terror in a single bloody gesture, or illustrating an unspoken though tenuous connection that transcends nationality. But the frequency with which the poems sacrifice their narrative clarity for the sake of a good-sounding line suggests an aesthetic stance rather than casual oversights—a stance which assumes, a little too quickly, the understanding of the audience. The poet winks as if to say, “Well, you know what I mean!” and the reader, dazzled by all of the rhetorical flourishes, winks back, happy to be implicated in such an amicable conspiracy.

Mark Strand once said that the point of truth comes when a poet goes from writing private poems in a public language to writing public poems in a private language. The least successful efforts of Un-American speak in a public language not unlike what’s found on Twitter, which values affect, quotable soundbites, and—most crucially—a certain level of consensus between readers and the writer. This comes with a cost, though; when the poems try to broaden their appeal, they dull the vividness of the specific by turning to the generic. In the book’s title poem, the speaker recounts a Fourth of July afternoon where her father “draws God’s shadow right / down to the horns,” and bees “burn / their tongues on sprout /chili peppers, turning the honey mad,” articulating the insidious nature of Independence Day. All those sheathed edges of history, like the slavery America relied on for its labor, are inscribed in God’s horns, the maddened honey. Yet, in a gesture typical of this book, the speaker then blunts the irony by abstracting the camera’s focus—“Fireworks splash against my parents’ / American Dream”—as though the poems forget that their most piercing social critique inheres in the family’s narrative itself. The poet need not always flash the larger picture in neon.

Paradoxically, however, the poet finds her most private—and compelling!—language when speaking behind a persona, not as herself. Geter’s ambition to write publicly-minded poems is best realized in the “Testimony” series—four elegies dedicated to Sandra Bland, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, and Michael Brown, of which the last three are persona poems. As the poet invites us to listen in on these intimate conversations between herself and these lives, the true power of Geter’s vision emerges: one that challenges our more static notions of citizenship, belonging, and family. Though Un-American is ultimately an uneven book, it readily displays the poet’s considerable gifts, among them a voice in equal measures angry, compassionate, and sorrowful, which ramifies throughout the collection and in my soul:

III

Perhaps the greatest danger a poet faces as he or she grows older—when it comes to their poems, I mean—is the slow easing of manner into mannerism, as in the case of, say, William Wordsworth, whose late poetry my friend once described as “self-karaoke.” It’s one thing for an artist to honor and sustain one’s obsessions, which are fundamental to the shape and direction of an imagination, and another to sustain one’s art through recycled success, which could be termed an aesthetic nostalgia. For nostalgia, as Henri Cole says in an interview with David Roderick, “is death for an artist.” In Cole’s tenth collection of poetry, Blizzard, one finds all the familiar hallmarks of his mature style: the free verse sonnets populated at turns by his parents, an ark’s worth of introspective animals (domesticated and wild), those bracing (if sometimes opaque) similes, and an understated but ubiquitous mood of sadness (or is it loneliness?). But far from self-cannibalization, these poems rely on an ever-stricter austerity to refresh themselves; like the sculptures of Giacometti, spareness only sharpens their intensities:

Cole has become our greatest poet of domesticity since Elizabeth Bishop. His poems take for their occasions frying mushrooms in butter, eating lingonberry jam on toast, peeling potatoes, watching the news, or (as in the lines above) recycling and composting at home—though these external occasions are the instruments Cole uses to address his deeper concerns. Like Bishop, he prefers to approach emotional content obliquely, through his surfaces. And while most of his poems are spoken in the first person and make direct, sometimes shockingly naked claims about the poet (“Me—I have no biological function”), such disclosures always rise out of, or give rise to, artifice (“and grow / like a cabbage without making divisions / of myself”) rather than unwitting Freudian slips. Which is to say, Blizzard’s ambitionis not authenticity but art.

Since Middle Earth, published in 2004, Cole’s poems have pared their more ornate exteriors down to a simplicity of expression characterized by plainspoken diction, straightforward syntax, and unadorned images, enacting at the same time a richer psychological complexity. In this shift from an overt technical virtuosity to a quieter focus on the inner life, he resembles the Robert Lowell of Life Studies rather than Bishop. Cole, however, has none of the grand scope or automatic authority of Lowell, who couldn’t resist his role as a public poet. Even at his most political, Cole only ever speaks as an individual, from a position of privacy:

Here framed in personal terms is the AIDS crisis, only one of the egregious failures of the Reagan administration. The speaker’s friends return from beyond the grave, occasioning invective, lament, self-criticism, and joy, all at once—a mix of tones where one doesn’t overshadow another in intensity or balance. (As I say: psychologically complex.) The result is a tension which the poem stretches into a taut, momentary connection between the living and the dead. In a delicate reversal, Reagan is regarded as a sidenote and mere accident of history (“another / hard-right president”) while these men return vibrant and wise. The speaker’s memory, in the words of Robert Lowell, has given back to each figure “his living name.”

Memory is the mirror into which a poet continually gazes, though each poet, if they stand looking at their reflection long enough, eventually feels alienated from it. The means by which a poet compensates for and overcomes this distance often dictate the terms of their late style. In Lowell’s case, he aimed his attention squarely on the figure he saw in the mirror: in The Dolphin, for instance, he dressed and re-dressed his reflection in so many different ways that the poems piled up like a mess of costumes, which amounted to a narrowing of his gift. The poems of Blizzard, however, address the distance between the mirror and the poet’s reflection by scrutinizing the abyss between them:

I admire the careful ambivalence here, how the speaker states his need for emotional immediacy, even if it comes in the form of his worst impulses; and then the self-reproach, not for indulging his infatuation, sadism, and lust, but for nearly conflating the memory of them for the real thing. To substitute the representation of experience for experience itself is a form of idolatry lyric poets are particularly susceptible to—though Cole never reaches for such cheap salvation. “I think maybe my real subject is writing as an act of revenge / against the past” he writes in the book’s final poem, “Gay Bingo at a Pasadena Animal Shelter,” as though the poet can only connect to the past by adjusting his orientation to it, by widening his perspective. If nostalgia is both a retreat into memory and a revision of it, then Blizzard rejects nostalgia for a clarifying irony that achieves a double vision: experience as it has been recorded, set against experience as it has been remembered; the public view set against the private interpretation. That Cole would have us live in this distance rather than reconcile it is a testament to his courage as an artist, and the rigor of his craft. I carry these poems with me the way a medieval pilgrim would have carried a hollowed gourd filled with water. He is one of the indispensable poets of our age.

Christian Detisch’s poems, essays, and criticism appear in 32 Poems, Image, Blackbird, Unsplendid, and elsewhere. He currently works as a hospital chaplain in Asheville, North Carolina, where he lives with his wife.