Split the Lark: Shara Lessley on Contemporary Poetry

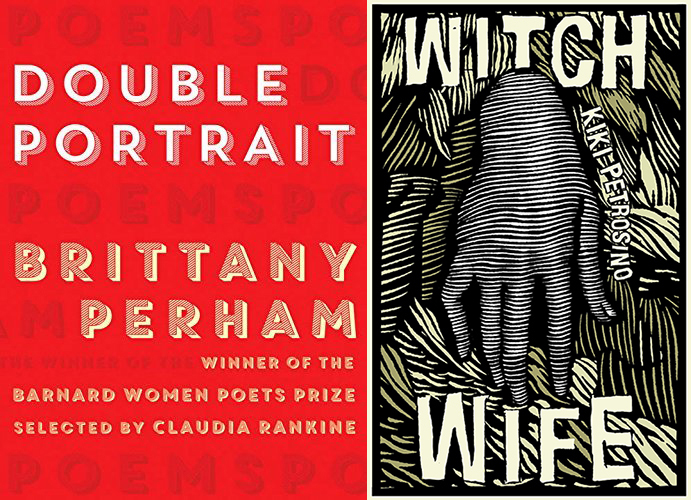

Double Portrait, by Brittany Perham. W.W. Norton & Company, 80 pp., $26.95.

Witch Wife, by Kiki Petrosino. Sarabande, 60 pp., $16.95.

I buy pencil sets and notepads in the gift shop partly as a means of distraction. Plonk the kids in front of a painting at London’s National Gallery to sketch, and my husband and I might steal some time taking turns between supervision and circling the masterworks. In Room 41, my daughter and son sprawl on the floor before Van Gogh’s “Sunflowers,” approximating on paper the painting’s intricate patterns and shapes. I snap a photo of them with my phone. A double portrait of sorts: brother and sister—two figures in a curated space, their identities conflated by the frame. We’re used to pairs not only in visual arts, but also in poetry. A metrical foot equals two measurable syllables. Speaking of meter, the spondee’s equally stressed units lend emphasis to the phrase or sentence that houses it. As Robert Hass points out in A Little Book on Form, the spondee is a pulse of sorts, a heartbeat. At the level of the stanza, there’s the elemental couplet: two successive, self-contained lines, some of which are deemed “heroic”—the iambic building blocks with which Chaucer constructed his Canterbury Tales, or those later employed in well-known works by late seventeenth and early eighteenth century poets Dryden and Pope. Within these individual couplets, writers often engage two or more like sounds. The intersection of consonants or vowels in proximate lines binds words via consonance and assonance, as in the following pair of slant rhymes by W.H. Auden: “This like a dream / Keeps modern time, / And daytime is / The loss of this;” (“This Lunar Beauty”). A number of poems, remarkably, are two lines in their entirety, as in Frank Bidart’s dazzling spin on Catullus: “I hate and love. Ignorant fish, who even / wants the fly while writhing.”

But lyric pairs extend well beyond individual stanzas and sonic orchestration. Many poetic forms depend on duality as an essential structural component. The ghazal’s opening couplet (or malta) establishes a pattern via its refrain (radif) that’s repeated every other line for the duration of the poem. The sonnet’s “little song” is divided into halves we identify as octave and sestet. Even the pantoum and villanelle, constructed with three- and four-line tercets and quatrains, rely on doubles. In each case, two lines embedded within the opening stanza are separated throughout the poem’s body only to reconcile at the end. The formal effect is a kind of spiraling, a double helix of intonation and rhythm. As a reader, it’s greatly satisfying to watch a pantoum depart from its dramatic occasion, only to invert the opening linear pattern and revisit its triggering subject in the final moments of the poem. This circularity, of course, depends wholly on two dynamic lines buried within the first quatrain. A similar pleasure occurs in a villanelle when, in the final two lines of the poem, the sentence or phrase whose rhymed partner has been held at bay for five stanzas finally rejoins its mate. These, of course, are technical duos. Poetry, likewise, contains multitudes of implied pairs or antithetic parts essential to facilitating lyric tension. A few examples—call and response, question and answer, turn and counterturn, public and private. The poet engages language that’s concrete or abstract, descriptive or declarative. And at the heart of the lyric: that powerful juxtaposition between that which is articulated versus that which goes unsaid.

I

I’m thinking about all of this—without really thinking about it—when I reach Jan van Eyck’s double portrait at The National Gallery. Here, at last, is the Dutch master’s visual narrative of great sexual morality. On canvas, a man in a fur-lined robe takes a young woman’s hand in his. Although I’ve seen reproductions dozens of times, only now do I appreciate the painting’s details: the crisp lace of the ingénue’s headdress, the velvet folds of her dress gathered up in round waves, how they counter the hard lines of the nearby bed fitted with red curtains. The couple stands beside an open window, a cherry tree peaking through the pane. Oranges (most likely imported fruit, designating wealth) spill across a table, one bright citrus globe left isolated on the sill. Light moves across the subjects’ faces. Something shifts, and I begin to see a series of doubles within the portrait. On the floor, two pairs of shoes: one wooden; the second, cardinal silk. In the center of the room, a mirror round as an eye. And there, in its reflection, everything in the room multiplies. Here, van Eyck duplicates the focal couple in miniature. But within the inverted glass he also paints another pair: the subjects’ counterparts, it seems, dressed in red and blue—who are they?—entering the room in order to complete the scene, or interrupt it.

There are many disagreements about van Eyck’s “The Arnolfini Portrait.” Part of its appeal, perhaps, is the extent to which the painting invites speculation. Unlike single subjects, twosomes, especially those like van Eyck’s artfully constructed couple, introduce layers of mystery and tension via their proximity and juxtaposition. A pair, in other words, competes for compositional attention. Although their identities are conflated for public viewing, we wonder about the nature of the subjects’ private relationship. We also ask ourselves what their staged interaction implies about broader social or psychological dynamics. Who has power, the upper hand? Is there some unspoken dialogue or attachment between the figures, an obvious rapport or evidence of concealed tension?

It’s this kind of restless duality that drives Brittany Perham’s sophomore volume. Winner of the Barnard Women Poets Prize selected by Claudia Rankine, Double Portrait is a delightfully obsessive and ambitious book that labors against the notion of the lyric as the song of “one” self. Like the visual arts, whether considering the relationships between child and parent, body and spirit, health and sickness, or the political implications of the individual versus the general populace, Perham’s “double portraits” depict human complexity and plurality. Although her verse isn’t ekphrastic, Perham organizes the collection in the mode of museum curator or art conservationist. As per the author’s note to readers, each entry:

… appears with an archival number, which serves to catalog the poem in a series. While the book presents one possible order for each series, that order is neither linear nor fixed. Imagine, instead, that the Double Portraits in each series could be viewed together in one room of a gallery. The way you proceed through each room is up to you, and may change each time you enter.

In light of the “project” books that currently dominate American verse, Double Portrait’s “structure-less” form proves quite radical. Even the individual titles themselves (“DP.b.11,” “DP.agp.15,” “DP.wor.99,” for instance) resist the kind of linguistic specificity, i.e. “framing device,” we come to expect as readers of contemporary poetry. Yet, despite Perham’s assurance “that order is neither linear nor fixed,” as a physical object the book maintains an inherent organization. Double Portrait isn’t a video installation with various links to poems, in other words, nor are its pages boxed loose leaf like a deck of cards. Peruse Double Portrait’s table of contents and you’ll find four distinct series that eventually reveal themselves as subject- or mood-related clusters. In this contradiction—the author’s vacillation between structural liberty and inevitable constraint—we get the first impression of Double Portrait’s chief concern: the tenuous negotiation between what’s fixed and what’s free.

This is typically the point in reviewing a book when I hold up a series of selections for close reading in order to suggest something about the poet’s habits, ambitions, and near misses. In Perham’s case, however, it’s the collection’s macro level—particularly how Double Portrait enacts and reflects formal elements of the ghazal and pantoum—that I find excitingly fresh. This isn’t to suggest that the individual poems aren’t worth scrutiny. With the conversational energy of O’Hara and rawness of Addonizio, the writing in Double Portrait is subversive and bright. It’s also emotionally fearless, which serves its author as both a strength and liability. In “DP.b.21,” a sprawling four-page poem that builds momentum via anaphora, Perham renders one of the wildest aubades I’ve encountered. The poem opens with the iambically-driven declaration, “I wánt to kíss you nów I wánt to kíss yóu”. Although the line initially sounds like pentameter, an extra syllable introduces the emphatic spondee, kiss you. Desire, here, is wholly unabashed and urgent—so urgent, in fact, that Perham fuses the sentence, opting to forego punctuation altogether as the poem rushes down the page until, as is the case in traditional aubades, the sun rises and the lovers go their separate ways:

… in the morning before

you’ve eaten

one sweet bite of the apple left by the bed

in the French tradition I want to kiss you

when at night you set the apple very red

by the bed I want to kiss you & in bed

when you say this is the French tradition

of lovers I want to kiss you though I’m skeptical

I want to kiss you & when you say I want to kiss you

I want to kiss you more & while I’m kissing you

I want to kiss you again & again I’m sad

while kissing you nearly weeping

while kissing you you’re so close

to leaving & when you’re gone I kiss you

in memory & even now kissing you gone

gone even now kiss even now I’m kissing you

As reflected in the lines above, “DP.b.21” is a quick-paced pas de deux between stability and chaos. Perham’s linguistic patternmaking—anaphora, internal rhyme, the refrain, as well as recurring images and gestures like the apple and act of kissing itself—anchors the poem structurally, while its emotionally frenzied speaker seems to run off the rails. Like its counterparts in Double Portrait, the poem reveals the competing impulses of attraction and repulsion. At one turn, the voice is obsessively focused (I want, I want, I want), the next relatively unhinged. “[W]hen you’re gone I kiss you,” she announces (note that the word “want” now falls out of the phrase, making the claim literal, despite the lover’s absence). At this point feeling trumps logic altogether, as language breaks down at the level of sense and grammar: “… kissing you gone / gone even now kiss even now I’m kissing you”.

Reading “DP.b.21” on the page, I’m overtaken by the first section’s energy. There’s real pleasure in its directness, the simplicity of Perham’s diction, and the extent to which she recharges and renews the stanza’s limited range of phrasing. But where the poem leaps next is stranger and even more invigorating. Replacing “kiss” with “miss” via rhyme, the second verse paragraph begins with the speaker’s confession—or is it concession?—that “I miss you meteorically metaphorically.” Characterizing physical and then psychological turmoil, Perham then riffs for another twenty-plus alliterative lines, one of which contains the admission “… I miss you / murderously” (emphasis mine). Here, “DP.b.21” turns joyfully diabolical as the third section announces flatly, “I want to kill you when I wake up / I want to kill you all day & after I kill you / I want to nap & wake up killing you / again when you’re leaving I want to kill you / when you leave after kissing me …” In the above lines, Perham returns to the poem’s original point of departure, the “love sickness” typically associated with the aubade. Even as the narrative comes full circle, however, all is not as it seems. As in the first section, the sun rises. The lovers part. Morning gives way to mourning. Although desire remains steadfast, affection is now laced with bitterness as the couple’s initial passion gives way to a slower, perhaps steadier, burn.

Perham brilliantly undercuts the high drama of “DP.b.21” in its fourth and final section. Flush against the right margin of the page, the utterances now seem little more than an exhausted whisper as the speaker backpedals. “I want to keep you from harm keep you / from crying,” she concedes, “… by keeping you close I want to keep you close”. Whereas the previous verse paragraphs read as universal claims that might be uttered by an obsessive archetype, Perham now introduces a series of highly particular images: “I want to keep … / your middle-of-the-night thing for Wheat Thins / & omelets I want to keep you cooking / especially your pasta sauce I want to keep it / in Tupperware in the freezer …” Hyperbole lapsed, the poem wanes as lust, grief, and loathing reveal subdued domestic intimacy. As the poem draws to its end and the couple cycles through summer and into winter, the speaker seems to settle in, surrender. “I want to keep your breath in your chest / for longer than my breath will keep,” she concedes, before the poem concludes with the simple iambic utterance, “I wánt to kéep you képt”.

In many ways, “DP.b.21” is exhausting. Its cadences and emotional register overpower its romantic subjects, as well as Perham’s readers. Yet, the poem is also undeniably invigorating, its enmeshed couple oddly recognizable. As in double portraits by painters like David Hockney, Perham marries artifice with elements of realism to give an impression of people who are focused yet frayed. As Perham’s strongest poems reach a fever pitch, it’s formal precision that keeps them from lapsing into excess. Couplets appear throughout the collection, as do list-poems and catalogs—a natural fit, given Double Portrait’s archival structure. Most successful, however, is the author’s exploration of pair-dependent pantoums and ghazals (often loose). “DP.f.00,” for example, considers the pressures and intricacies of an adult child who longs for both connectedness and independence. Witty and vulnerable, the speaker is also incredibly self-aware. “We have this one thing in common: I think about myself almost all the time,” observes the poet of her parent, and then goes on to add:

She, too thinks about me almost all the time, she says, “because I’m your mother.”

When you have a kid, you’ll understand; when are you having a kid?”

For the reasons above, I think it’s better I never be anyone’s mother.

I know I’d better die before she does, but she says no, she’ll never let this happen.

I still somehow believe that the greatest power in the universe is my mother.

When she’s mildly annoyed, or when I’ve been away for a long time, she calls me

by my full name, Brittany Titania, which is the way of every mother.

There are certain words you can never say too many times, especially when crying:

mommy, mama, mummy, mom; where is my mother; I want my mother.

“DP.f.00” takes some formal liberties with the ghazal. Rather than invoke her signature somewhere in the final couplet, as per the traditional makhta, Perham instead weaves “Brittany Titania” into the stanza that precedes it. More interesting, however, is the way Perham doubles down on the makhta itself. The poem not only embeds the poet’s own name, but an additional string of monikers representing the female parent—mommy, mama, mummy, mom, mother. As is the case throughout Double Portrait, here mannered repetition increases linguistic texture while conveying fierce human attachment. The final couplet above also reminds us that poetry’s medium is the body; its sounds, when read aloud, turn physical. Feeling the notes spring to life in our throats as the speaker cries out for mommy, mama, mummy, mom, as well as the twice invoked, much yearned-for mother, we recognize the speaker’s emotional crisis, as well as the central tension of Double Portrait: that is, the dizzying vacillation between connection and estrangement, and the limitations of language to contain or express either of the two.

Ralph Waldo Emerson reputedly criticized the ghazal for its discordance, comparing the Persian form to beads unstrung from a necklace. Yet, lack of linearity is one of the form’s great gifts: that its cohesion comes through secondary sound patterns; particularly, the single syllable or curtly phrased radif, (i.e., the refrain, “mother” in the aforementioned “DP.f.00”) that connects its otherwise disjointed couplets. We see repetition’s binding effect not only in Perham’s individual poems, however, but also at the book’s macro level as its archival “structure” presses against the Western inclination toward cohesion. Enacting what Agha Shahid Ali describes in Ravishing DisUnities as the ghazal’s central charm, Double Portrait’s poems stand “each autonomous, thematically, and emotionally complete,” while the collection’s random pairings ultimately result in a “profound and complex cultural unity, built on association and expectation of the human personality and its infinite variety.” Like the ghazal’s individual couplets, in other words, Perham’s “double portraits” become a book-length study of a particular theme and its variations whose consistency stems from a mood that’s both ardent and melancholic.

One of the greatest ironies of Double Portrait is that, despite its thematic focus on pairs, the first person perspective dominates the collection. Reading the book, it’s as if two actors dramatize their relationship on stage, one of the characters unable to speak. Imagine, for example, the woman in Grant Wood’s 1930 painting, “American Gothic” sharing the more sordid details of her life while her counterpart, the stone-faced pitchfork-wielding farmer, stands mute beside her. “A pronoun never loved or grew,” asserts Perham in a pantoum of eight lines whose epistolary inquiries ultimately reveal themselves as rhetorical questions. Perhaps at times, it also held its breath. Granted, Perham’s poems occasionally employ the second person. In these cases, however, “we” rarely denotes shared experiences. Instead, Perham utilizes the pronoun to assert experiential claims about the private lives of two people. “In familiar corporate hotels, / we’ll have to begin to talk, when / drinking room-service wine / and fucking is what we do best,” asserts one speaker in a pantoum about a Skype-dependent long-distance relationship (emphasis mine). Elsewhere, a love affair unravels over nine rhymed couplets: “We argued at breakfasts. We argued on drives / We argued in front of our friends and their wives” (“DP.b.11”). Whether or not an ex-lover might dispute the aforementioned details doesn’t really matter, as it’s clear that Double Portrait resists universal consensus. As with her intensely compressed pantoums, in which two unaltered lines move through a series of stanzas in order to generate nuance, Perham depends on incantation, repetition, and variety. She is a poet deeply invested in the way direct feeling and conversational speech is complicated by juxtaposition and interaction. Much like the shuffling of the pantoum’s ghostly couplet that makes a first impression in the opening stanza only to resurface and invert its meaning by the poem’s closing lines, the pleasures of Double Portrait are its back-and-forth movements, its various arrangement and rearrangements. As Perham demonstrates, there’s much to mine when it comes to aversion and reconciliation, when what initially seems like sameness—of feeling, phrasing, or form—turns out to be the mechanism for a far more telling sleight of hand.

II

Much has been made of the female subject in van Eyck’s “The Arnolfini Portrait,” whose high-waisted gown sweeps the ground, spilling over in lavish folds. Is she Arnolfini’s bride? His spouse recently deceased? A belt below her bust and voluminous layers of fabric give the impression of a swollen mid-section. Pregnant or not, the woman’s belly suggests fertility. At its simplest, van Eyck’s painting shows a couple standing side by side, their hands touching. Yet, this double portrait, the first-known in a domestic setting, reveals much about the pair’s gendered obligations. While the darkly-robed and strongly postured Arnolfini epitomizes authority, his unnamed female counterpart reads otherwise: it’s the girl’s modesty, her physical beauty, and an ability to bear children that van Eyck emphasizes. Beginning with a creation myth and then moving through girlhood, young adulthood, and into marriage, Kiki Petrosino’s third collection interrogates the kinds of conflicting pressures of womanhood idealized in “The Arnolfini Portrait.” The book’s title, Witch Wife, quietly highlights the two conflicting options afforded to a girl as she comes of age. Should she choose a self-governed life playing the part of magical old maid, i.e., witch? Or, embrace the culturally sanctioned role of married family woman, thus adopting the role of wife? Within her title, Petrosino also embeds a pun that frames the collection’s latter half: when it comes to the sanctity of marriage, which kind of wife should she strive to become? A caretaker? Happy homemaker? More still, how should she behave? In good times and in bad? In sickness and health? For better or worse—which begs readers to ask for better or worse for whom?

Although Petrosino doesn’t identify her poems as double portraits, Witch Wife consistently explores relationships between paired figures, and/or competing binary tensions. An early poem, “New South,” for instance, puts a child in dialogue with her collective female ancestors who “[march] by night / under southern pines / or a dream of pines.” As history rises up to chide the “light girl, light girl” at the poem’s center, the foremothers warn their descendent about the dangers of her genealogy. “[D]on’t you ever tell them about us,” admonish the matriarchs, “don’t you ever tell.” As is the case throughout Witch Wife, the speaker in “New South” navigates layered modes of identity and time—the past and the present, darkness and lightness, self-assertion and denial. While “New South” doesn’t explicitly mention racial identity or “passing,” its final lines turn toward self-scrutiny. Here, Petrosino clearly articulates the tensions between history and memory, geography and the dream-state, secrecy and revelation: “I look down hard / at my hands / white webs opening,” she writes, “somehow / strange / to myself.” It’s this sense of estrangement and self-alienation that proves critical to Witch Wife as the poet explores not only racial consciousness and ancestry, but subjects such as self-love, acceptance, and female body image. “Whole 30,” for example, finds its central figure “ballooned to a specific kind of ugly,” while the speaker in “Sermon” begs to know “Who shall change my vile body into a glorious body,” before finally concluding that “… I [shall] come into glory, Lord / when I drown when I drown when I drown when I drown.”

To “drown,” of course, is to suffocate under water. But the word suggests an alternate meaning: that is, to overwhelm or render inaudible; the way, for instance, cultural pressures can sometimes drown out the singular voice, or undercut one’s understanding of individual needs or desires. In its third section as Witch Wife explores the latter definition—particularly, what the female body is expected to bear both physically and emotionally, especially when it comes to conception—the book truly comes into its own. In her essay “Mommy Poems; Or, Writing as the Muse Herself,” Rachel Richardson suggests that what’s most interesting about motherhood poetry isn’t “the narrative—not the babies or the birth story or any of that” but how having children alters the female writer’s view of the world around her. Richardson calls this shift “the sharpness of perception.” For most poets writing about motherhood, this dexterity begins in the first trimester and then moves forward postpartum. There are countless poems, in other words, written from the perspective of expecting parents, new parents, older parents, grieving parents. What sets Petrosino’s work apart is her remarkably candid take on a woman’s psychology when wrestling with the question of whether to become a parent at all, and the clarity with which she articulates this dilemma. “Prophecy,” for instance, assails its speaker with a series of back-handed compliments and idealizations that frame motherhood as part of some grand design. “You have a good belly for twins,” the poem opens, “I can see you / at thirty weeks, your skin bright as automotive paint / Rejoice, now: your life will be full of blessings.” Here, Petrosino’s deft exploitation of the second-person perspective underscores the idea that, as a woman, to give birth is somehow compulsory. On one hand, you wields a god-like power, one capable of granting “blessings.” The third line, which introduces half of the poem’s refrain, casts “Prophecy” as an annunciation of sorts, one that demands the woman immediately “rejoice” at the very prospect of pregnancy. Yet, the you likewise reads as self-referential, revealing an otherwise hidden inner dialogue. As “Prophecy” progresses, its speaker tries to sell herself on the idea of the potential offspring who will “wear little caps, little suits, on the bus. / … munch animal crackers under a striped shade.” Ultimately, however, she remains unconvinced and castigates herself in the poem’s final moments by privileging her youth and physical attractiveness: “… you have a good belly / for now. Rejoice in your blessings, you fool.”

It’s worth noting that “Prophecy” predicts not one birth, but multiples. The oracle-poem, in fact, spills over with doubles including not only the unborn twins, but also the counterparts I and you, pairs of hats and clothing, the woman’s body pre- and post-pregnancy, and a dish of almonds sprinkled with two ingredients—lemon and salt. “Prophecy” is also a villanelle, meaning the last two lines of its final quatrain finally meet after cycling separately throughout the poem’s preceding five tercets. Like Perham in Double Portrait, Petrosino proves herself deeply invested in formal experimentation. Witch Wife contains ghazals, prose poems, a loose pantoum, narrative poems, a sestina, and free verse entries in dialogue with Anne Sexton (“I have gone out, a possessed witch , / haunting the black air, braver than night”), who serves as a shadowy lyric godmother. Most abundant, however, are villanelles, which take up almost half of the collection. In fact, what follows the aforementioned “Prophecy” is another villanelle, and one of Petrosino’s most arresting. If “Prophecy” implores its would-be mother to celebrate her untapped fertility, “Confession” reveals her reluctance to answer the call of duty. Instead, the speaker expresses her ambivalence about the prospect of motherhood, as well as a sharp anxiety concerning the possibility of accidental pregnancy. If, by title, “Confession” signals not only an admission of guilt but also the need for absolution, the poem’s body asks whether it’s wrong, really, for a woman to guard her independence and opt for a future without children. “Every month I decide not to try / is a lungful of gold I can keep for myself,” Petrosino begins, emphasizing the speaker’s agency and vividness, as well as her desire to hold fast to what’s valuable. What follows is an unsettling mix of apprehension and tenderness via a direct address: “Still, I worry you’ll come to me anyhow // & hitch your hiccupping bud. My dear / I don’t want to be got …” That the woman envisions the “hiccupping bud” (i.e., the heart in utero) is telling. Though confined to the imagination, the animated fetus lives, its blood pumping somewhere in the ether. Despite professing not “want[ing] to be got,” the speaker is of two minds and remains haunted by what’s possible. One moment the unconceived child is sprite-like, casting spells. “You keep spinning / through the woods,” writes Petrosino, “on green stars of pollen.” The next, she appears to bait her would-be parent: “Did you leave sweet jam on the sill?…” Yet, however strong her temptation, the speaker resists the unborn child’s beckoning. Declares Petrosino four times throughout the poem, “Every month, I decide not to try …”

With its circularity and relentless refrain, the villanelle is well-suited for obsessive subjects. True to the form, “Confession” recycles but never fully releases intimate feelings and ideas. As her speaker vacillates between self-determination and paranoia, Petrosino proves how well the villanelle embodies complex patterns of private thought and self-contradiction. This becomes clear in the final stanza, as the poem proves itself more concession than confession:

Lately, I’ve dreamed of

quilts stuffed

with bees; it’s a thing. Yet I don’t see

why I worry & worry. You come to me anyhow

every month I decide not to try.

I love Petrosino’s rendering of the dream-quilt, which conjures the infant’s first blanket—a “made” thing—whose patterned cells have been stitched together, as per tradition perhaps, by a grandmother or aunt or even the mother-to-be herself. Petrosino’s quilt isn’t the ordinary comfort item with which nurseries are decorated or babies swathed, however. Rather than filled with downy cotton, its interior hums with winged things that sting. “Stuffed with bees,” the blanket holds a hungry swarm, one that’s notably trapped. The bees’ honey-colored bodies also gesture back to an earlier image in “Confession”; that is, the untapped and closely guarded “lungful of gold.” Although the speaker questions the validity of her misgivings (“I don’t see / why”), she continues to “worry & worry”—the twice-repeated word for anguish placed side by side, further emphasizing her self-torment. Yet, as the paired refrain reconciles, at last, in the quatrain’s final two lines, what the speaker in “Confession” refuses to conceive in body she instead manifests in mind. “… I worry & worry. You come to me anyhow,” yields the woman, “every month I decide not to try” (emphasis mine). Here, at last, is the poem’s ultimate paradox: despite the woman’s choice to prevent it biologically, the phantom child lives and breathes and makes mischief as the imagined product of her mother’s own making.

Something magical happens when a poet finds a subject that challenges her to marry emotional vulnerability to formal dexterity. In Hymn for the Black Terrific and Fort Red Border, two radically different books, Kiki Petrosino proves herself a highly capable and inventive poet. Witch Wife, too, is an equally engaging collection with a number of moving poems—“Elegy” and “The Child Was in the Woods” are standouts—and the book works well to answer in multiple ways the question with which it opens, “Little gal, who knit thee?” But in Petrosino’s poems about reluctance to become a mother, readers discover something new and remarkable: a quandary whispered about but not often publicly discussed. Here, Petrosino widens and beautifully complicates the ongoing conversation Rachel Richardson characterizes in her essay. If, as Richardson argues, one’s view of the surrounding world sharpens with motherhood, especially after childbirth, what Petrosino demonstrates in Witch Wife is that an increased self-awareness begins with the very prospect of parenthood as a woman seesaws between distinguishing what she wants for her future from that which is socially accepted or expected. Often, the two choices are at odds, as Petrosino playfully demonstrates in the paired villanelles “Ought” and “N/Ought.” “We’ll have to hurry if we want to get started, / It’s high time to consider beginning at all,” she asserts in the first poem. But will the speaker, despite her enthusiasm, succumb to the pressures of starting a family? If the collection’s title begs its central figure to choose which wife she’ll be, the final poem of the book, “Purgatorio,” suggests that the woman ultimately remains undecided. “Things must change,” she concedes shortly after declaring elsewhere, “Don’t blame me for not bellying up” (“N/Ought”).

***

Organizationally, Double Portrait and Witch Wife couldn’t be more different. While Perham resists set order, inviting strangeness into an otherwise readily accessible book via arbitrary juxtaposition, Petrosino structures her odd and sometimes cryptic poems chronologically to help anchor the work. Regardless of disparities in aesthetics and tone, each poet has a clear understanding for what’s necessary to enhance her collection—whether structural instability and disruption in the case of Double Portrait, or thematic cohesion and linearity in Witch Wife. As a poet, Perham’s obsessive subject is the range of feeling that results from physical experience, whether sex or illness or relational conflict. Petrosino, on the other hand, writes freely of the body itself, including the particulars of its anatomy and sensual nature, although the crux of her poetry is the private nexus of thought. In Perham’s fierce rendering of the ongoing dramas of erotic or platonic love, or Petrosino’s consideration of how the expectations of gender relate to persuasion and self-preservation, we encounter poems of human contradiction.Of course, the paradoxical figures in Witch Wife and Double Portrait only make them more appealing. After all, Petrosino and Perham aren’t interested in female archetypes such as adversarial goddesses or biblical Marys. Instead, they dissolve the neat divisions between daughter and parent, woman and lover, wife and witch. By placing the authors of Witch Wife and Double Portrait in proximity and in dialogue with each other, we glean a much wider and more nuanced perspective of contemporary poetics and formal experimentation. In fact, having read their collections together, I like to think a double portrait might be made of the two: Petrosino and Perham held side by side in the frame while slight but telling details emerge from their poetry via patterns of structure, image, and sound.

Shara Lessley, a contributing editor, is the author of Two-Headed Nightingale and The Explosive Expert’s Wife. With Bruce Snider, she is the co-editor of The Poem’s Country, an anthology of essays on place and poetic practice. She lives in Oxford, England.