A West Branch Wired Exclusive

I met Emilie Staat Strong in a coffee shop around 2008. I was writing a short story, and she noticed the stack of craft books on my table. “You’re a writer,” she said. I said I was, and she said she was too. We’ve been friends since. Emilie had just earned a screenwriting degree from LSU and would spend years working in the local New Orleans film and TV industry. She worked many 16-hour days with celebrities like Miley Cyrus and Dave Franco. That kind of work schedule isn’t conducive to a high output of prose. I probably only got to read about one piece of hers per year. But they were always bangers. One won a fat prize. Another stunned me, but I think she may have ripped it up out of displeasure. I’m glad I was able to pry “His Neighbor’s Yard” from her hands before it hit the shredder. It’s a brilliant touchstone of the era. A disaffected man, capable of anything, searching for connection.

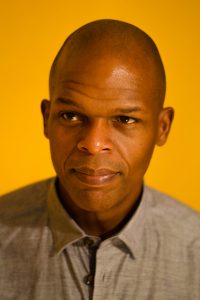

Kristina Kay Robinson is a person, but also a spirit. She was one of two other Black students in the creative writing program at University of New Orleans besides myself. A poet by training, I would soon learn it didn’t do her any justice to apply labels. Writer, performance artist, editor, publisher, curator, historian. If it’s related to storytelling, she’s mastered it. But not just any stories. New Orleans stories. Her family goes back many generations in the city, and she’s forgotten more about my benighted city than I’ve ever learned. I’m joking. Kristina forgets nothing. She’s a keeper of the city’s memory. “Dantòr” is an observation of the kinds of New Orleans people you never get to see in literary journals. Until now.

Years ago, a friend in Memphis told me of a brother somewhere on the eastern seaboard who had written something like 16 books. As is the way, we connected via social media. Although we’ve never met in person, we’ve formed a mutual admiration society. Ran Walker doesn’t waste time or space. His stories have the immediacy of a man sitting next to you in a subway and telling you that you’re more than you think you are. “The Tunnel of Love” seems like a light story on first blush. Then the reader considers the implication of being someone who can give love, but never receive it.

—Maurice Carlos Ruffin

Maurice Carlos Ruffin is the author of The Ones Who Don’t Say They Love You, which will be published by One World Random House in August 2021. His first book, We Cast a Shadow, was a finalist for the PEN/Faulkner Award, the Dayton Literary Peace Prize, and the PEN America Open Book Prize. His work has appeared in the New York Times, the LA Times, the Oxford American, Garden & Gun, Kenyon Review, and Four Hundred Souls: A Community History of African America. A New Orleans native, Ruffin is a professor of Creative Writing at Louisiana State University, and the 2020-2021 John and Renee Grisham Writer-in-Residence at the University of Mississippi.

KRISTINA KAY ROBINSON

Dantòr

“Please man. Just this time … take care of me, Co?”

“Come on,” I said, and lead the man whose voice had broken the dark and the woman he had with him to the back of the store.

The woman was young and quiet, too fucking quiet. She was wearing a pair of men’s jean shorts and a sports bra. Not fat, but her middle was loose and fleshy. She had this wide-eyed look of perpetual surprise. I gave them what they needed and tried not to look her in the face.

Back in front the store this girl was talking on a battered cell phone. Arguing with someone about shoe insoles and washing powder. She was a real pretty girl, with hair that looked like if she uncoiled it from the nape of her neck, would probably reach her butt. Once she walked inside the store, she hung up on whoever she was talking to. I watched the way the black and white stripes of her leggings moved across her legs, as she walked around the store all lazy-like, picking shit up, looking at it a long time, then putting it down. She’s stared at two boxes of Jiffy cornbread mix, like it made a difference.

I went inside to holler at Fadi for a second. Maybe get a little closer to her too. “I’m done. You know her?” I asked and motioned in the girl’s direction.

“Who? Panda? Yeah. She works across the street at the club. You never seen her in there?”

I glanced in her direction. Her eyes were red. I figured she had been smoking, but she could have been crying or both.

“How much?” she asked Fadi, holding up a toilet scrubber.

Fadi made a motion that suggested she look at the sticker. “It’s not marked, must be free.”

She walked up to the counter with a basket full of things. Toothbrush, ten boxes of cornbread mix, toilet-scrubber, detergent, a pack of sponge rollers, Lysol, and hand sanitizer.

“How’s it going over there?” Fadi nodded his head in the direction of the club across the street.

“You work over at Bottoms?” I asked. “How come I never seen you in there?”

“I’m only there a couple nights. But I know him,” she flung her hand in Fadi’s direction and laughed. “But I don’t know you. What’s your name?”

“Corey.”

“Well Corey … how about this … even if he stays home, you come see me, tonight, ok?”

“Why?” I asked. “Look like I got money or something?”

Panda giggled.

“No, but I think you’re cute,” Panda reached out and gave a few of my dreads a light tug.

I should have said something back. Anything. Squeezed the side of her waist. She would have liked that. Instead, I just stood there.

Panda stared at me like she was reading my mind. My eyes followed her out the door.

“I not going to lie, man,” I said, as I watched her stripes move through the glass. “I like lil’ one’s style.”

“Slow your roll, Co. You know that girl Peanutt? That’s her sister. They’re trouble.” Fadi laughed, but I could tell he meant it.

“That’s exactly what I’m looking for, dog” I answered.

I meant that too.

The power was out. My Paw was out of town and forgot to pay the light bill. I had the money to turn the lights back on but fuck it. I was about to cop an apartment and some real work of my own. I could sleep without lights for a couple days. I lit all the candles I kept on my drawing table. I needed to clean myself. I smelled like outside. Like a puppy dog, my mama would have said if she could smell me. The hot water from the bathroom steamed up my entire room. The tiny bathroom connected to my bedroom reminded me of a cell. Once in the shower, the sweat started to pour. I had to sit down to keep from passing out.

The water rushed over my head and Peanutt popped up in my mind when I closed my eyes. She worked at Bottoms from time to time and always needed two things when she saw me. That shit to get her up, before work, and that shit to get her back down, once she was home. I didn’t know she had a sister. But I was gonna pretend like I still didn’t. I had messed around with her a few times before I realized how bad off, she was. Then there was Kalo. My baby girl. All I could do was lie to her about it all.

Damn near two in the morning, and still too hot to sleep. My Pa was trying to wait me out, make me pay the bill, probably, but whatever. He had been doing this shit since I was ten years old. Leaving and returning with little warning. I called Fadi to see if he was done at Habibti’s and felt like dipping through Bottoms. I was really trying to see that girl. When he pulled up, I was happier for the air conditioner than the blunt he passed to me.

“Xavier back from Miami yet?”

“Yep,” Fadi said. “I talked to him earlier. He said tomorrow and we’ll be all good.”

Inside Bottoms, we saw each other at the same time. Panda was leaning up against the bar talking into the side of this man’s neck. She stood in place, but moved all the loose flesh on her body, which was just enough for a good show. The man slid money in the little bag she wore around her waist. She looked past him, straight at me. Her hair was all hanging down looking like falling water. Her snow-white top and bottom were slashed all over the place, nipples poked out the holes in her top. I was impressed by how much like a bride she looked. I wished I had flowers for her. I wasn’t really hung up on the good girl shit.

When the song ended, Panda patted the guy’s shoulders, gave him a kiss on the cheek, and headed in my direction.

Fadi was already looking uncomfortable. I knew he was going to leave once he was done taking care of business. I could find my own way home, and if not, Fadi would come back for me. That’s why we were friends. When Panda made it over, I reached out to put my hand around her waist and pull her toward me a little. Not too hard, but just affectionately, to show her I wanted her.

“I think I’m good for the night,” Panda said.

“Oh yeah?” I answered. “Lucky you.”

“Yep, lucky me. I’m ready to leave. Want to go chill somewhere? We can have some real drinks instead of this watered-down shit.”

“Yeah, let’s go. But I don’t have a ride right now. You?”

“Guess we’re flying United. It’s all good.”

Out of her money bag she pulled out this black spool of cloth. When she unrolled it, turned out it was a real thin black dress that reached almost to the floor. I watched as she pulled it over her head. It fell soft and wavy, where it should, on her body and we walked out the club together.

“My place?” she asked.

I nodded.

The cab came quick. Panda said she was a regular customer.

“You talk real cute, you know that? Where you from?” I asked her, as we got into the backseat.

“Here, but I left when I was like fourteen. I just came back to New Orleans like 6 months ago.”

“Where you coming back from?”

“Honduras,” she answered.

“Panda’s your real name?”

“By real, if you mean the one I answer to, yes.”

“What about real by the one your mama gave you in the hospital?”

“My Mama is dead and I was born in a house, so there you have it.”

Usually, when I was with a girl, I didn’t ask many questions. This time I did and it brought something into the small space of the back of the cab that I hadn’t intended. I had blunt in my pocket, the driver seemed cool, so I asked him if it was okay to smoke. We were his last fare, he said, and as long as he could hit it, it was all good. I lit the blunt and the comforting odor made the air around the three of us lighter immediately.

“Where you all going again?” the driver asked.

“The Hill. Schaffield Dr.” Panda responded.

We pulled up to the duplex Panda stayed in and I tipped the driver an extra ten, good enough for a dime of his own. I got his number. He was cool people and I always needed a ride.

By the time we made it up the rickety flight of stairs, and Panda unlocked the screen door, and then the two locks on the wooden door, the entire front of my body was lit up. From the weed definitely, but from her mostly. She was so damn pretty. The tail end of her long ass hair rested at her waist. Right where her spine began to curve. I couldn’t keep my eyes off of the back of her.

“Damn, man. You’re fine as hell,” I said to her, as she twisted her keys in the door.

“It’s a little messy. Don’t judge.”

Panda’s apartment wasn’t messy, so much as there was a lot going on. It was a studio with a real big screened- porch connected to it. Her bed was out there. Plugged up, she had 5 box fans and 3 space heaters. There was a desk with stacks of magazines, adhesive, glue sticks, and pieces of scrap wood stacked on top of it. She had several racks of clothes, like in a department store. A clothesline ran from somewhere on her porch to the hook on the back of her front door. There were a few half-finished projects going on, mostly involving wood, paint, and pictures cut from magazines. One work in progress was a picture of a little- girl Panda, plastered on a background of Jiffy cornbread boxes.

The piece that was complete, she had hanging on the wall. It was a mix of painting and collage. Almost floor to ceiling, it was the body of a big booty, big breasted girl, in an outfit like Panda danced in, except this girl had the head of the Virgin Mary. All around her were other girls, or just their breasts or their butts. There were guns, and jewelry, and angels. All of that was framed by a tangle of tree branches.

“I told you,” she said, sounding just a little unsure of herself.

“It’s cool, ma. I’ve seen way worse, believe me. You’re an artist?”

“You could say that.”

“Me too.”

Panda rolled her eyes at me and clicked on the stereo system that was plugged up to a splitter, whose chord ran the length of the apartment and patio. She shut off her overhead lights, clicked another button, and the room was bathed in soft blue and turned on the music. Glow and the dark moons and stars shined as best they could in the dim of the house.

“This makes the mess, a little better, don’t you think?” she asked. “I’ma fix us some drinks. Sit down. Get comfortable. Every spot in here is soft.”

“Sade reminds me of my Mama,” I said as she turned the volume up.

The makeshift sofa, which was made up of two twin mattresses with a few mattress pads stacked on top one another and covered by Bob Marley sheets. Big pillows rested against the wall. It was all bookended by two mismatched end-tables. It was comfortable. The kind of sofa you never wanted to leave. Panda opened up a closet door, which turned out to be a small galley style kitchen. I listened to her clink around behind my back.

When she was done, she came and stood in front me with a tray in her hands.

“Want some?” she asked, nodding down at the tray, and handing me my glass. The Hennessey smelled sweet and strong. She set a pewter and mother of pearl tray on the beat-up coffee table. Then I could see the perfect, parallel, white lines on it.

“I didn’t know you fucked around, I said.”

“Just socially,” Panda laughed. “You here, so this is social.”

“You bought that in Bottoms? That’s Fadi shit. Its good.”

Panda cut the lines in half again.

I sat back and let the tangy, sweet tart taste enter my throat. The drip was the best part. I tried to stay away from it but some things it was hard to do sober. I gestured to the tray on my lap.

“I can help you,” Panda said and ignored my question. Her pupils were as sharp as razors.

“What can you do for me, Panda-bear?” I asked.

She stretched her body across the sofa, rested her feet in my lap. She looked cat-like in the blue light of her apartment.

“I can cook for you. I’m here all day, and most nights.”

“I don’t sell crack.”

She was quiet a few moments.

“They going to do you. You and the A-rab,”

“Who?”

“Xavier and his people.”

What the fuck was she talking about? I was Xavier’s people. I didn’t really know who the fuck this girl was, and how she knew who I dealt with, or what she was getting at. People threw crosses all the time to make you vulnerable. I thought about Fadi’s warning, looked at the door, and halfway expected somebody to kick it in. I had done the same thing myself.

“How do you know me and them?”

“I kind of, used to, fuck with Xavier …”

“Used to?” I cut her off. I didn’t have time for ambiguity; I had to know it all.

“Used to. I knew it was you when you told me your name at the store.”

“So why are you telling me?”

“I don’t know. I couldn’t not tell you,” she said, sitting up, her face closer to mine.

It didn’t make any sense. I didn’t know whether or if I believed what she was saying. I had known Xavier almost my entire life. The only thing I knew about Panda was that I had fucked her sister. But when Panda sat on top me, I couldn’t think of much else but where I was in the moment. It didn’t make sense to fall in love this way, but I knew it was already too late.

Panda’s bedroom on the porch felt more like home in the short time I had been there than the place I slept every night. It was a disconcerting feeling but one I gave way to. With the right combination of the window unit from inside, the box fans, and the one space heater she had turned on low, under her sheets was the perfect temperature. I was wrapped in her and her hair and couldn’t move. I didn’t want to.

I didn’t know if I ever wanted to leave her.

She got out of bed, and I sat back, watched as she opened up her little closet kitchen, and put oranges, cheese, and French bread on the tray from last night. She brought the food over to me, and went in the bathroom, ran some water, and did another bump or two. I tried to ignore that. She could do what she wanted, but she was right on the edge of where her recreation was turning into work. She came back out with a blunt rolled.

“ You told me you were an artist. What do you do?”

“Draw.” I said fixing my eyes on the scantily clad Madonna. I noticed now that she was holding a child’s hand. A child, who had the body of a skinny dog and walking a lion.

“I think most men worship the woman on my wall.”

“You’re right,” I answered staring at the collaged birds Panda had embedded into the veil of the Madonna.

I had to hit Fadi up, let him know that the plan had gone sour. I had to tell him what this girl said. He had called my phone a million times. We were supposed to meet up with Xavier to pick up our shit the next morning. If the shit was true, me and Fadi were going to have to deal with Xavier. The sure way.

We smoked two more fat cigars back to back, till Panda was able to lie back down. I tossed her ass around. She liked it. She said fucking me was like ballet dancing and tackle football. I bit her on the earlobes and squeezed her on her thighs. Back under her covers, Panda’s bed felt like a womb cut out of the block. Lying there face to face, finally too worn out to have sex again, there was so much I wanted to say to her. So much to ask. Panda turned on her side, her back to me. I held her tight and waited for some words to fall out of my mouth.

“What do you do if it rains in the middle of the night?” I asked into her neck, finally.

Panda sighed and pressed herself into me. “Nothing. I just lie here, and let it hit me.”

Kristina Kay Robinson was born and raised in New Orleans, Louisiana. Her writing in various genres has appeared in Guernica, The Baffler, The Nation, The Massachusetts Review, and Elle, among other outlets. She is a 2019 recipient of the Rabkin Prize for Visual Arts Journalism. Currently she serves as the New Orleans editor-at-large for the Atlanta-based Burnaway magazine.

EMILIE STAAT STRONG

His Neighbor’s Yard

He still remembered the security code to the Chandlers’ side gate, though it had been almost two years since he’d last helped Joe Chandler manage the backyard. Before all of this stuff with the virus, before Joe’s accident, before the divorce and Angela got the house and sold it. Before everything got so bad for him.

Why was he here, now, like a thief in the night? He didn’t want to think about the answer as he typed in the code and went straight to the shed, finding his way easily in the dark, as if this was his own place. He resolutely averted his eyes from his former property. He didn’t want to see what the new owners had done to the wide, open front lawn or whether they had removed any of the fruit trees from the back yard, which was flatter and shallower than the Chandlers’, based on its orientation in the cul-de-sac. He couldn’t look at it, not after everything he’d been through since it was his home. That place belonged to another life, a different man.

He was betting that Joe hadn’t changed the code for the shed either and Rita certainly had bigger worries right now. When the lock disengaged in his hand, he opened the shed door and paused for a moment to let his eyes adjust. He couldn’t flip on the light to look inside. He knew Rita kept odd hours and she might see, might call the police. He didn’t want to scare her.

What he was doing, taking all those tools that Joe had in the shed, he wasn’t hurting anyone by borrowing them for a short while to make some cash. He was the one who’d shown Joe how to manage this big hilly backyard of his and he had put so many hours of sweat equity into that yard, all for free. They wouldn’t begrudge him taking tools no one else could use right now. If he knocked on the door tomorrow, looked Rita in the face and asked her, she’d probably give them all to him. She would, he bet.

He stopped, knowing that’s exactly what he should do. Go sleep in his truck a few hours, freshen up at the truck stop two miles down the highway, then come back and ask Rita to loan him those tools so he could get back on his feet. She would say yes.

He shut the shed door and locked it up again. His eyesight was sharper in the dark than he would’ve thought months ago and he looked up the hilly yard, squinting to discern the old tomato plant beds and that wooden palapa he and Joe had built, ten – wait, fifteen or maybe even twenty – years ago, back before he’d become such a disappointment to Angela. They used to BBQ on the small cement platform, then carry plates and drinks up the hill to the palapa, back when he and Joe were middle-aged men, old enough to know something about the world, but young enough still to do something about it.

Suddenly, he smelled a waft of honeysuckle on the night breeze and his eyes pricked with tears. He remembered it was spring. The time was almost gone for putting in tomatoes and this would be the second season that the Chandler garden would lie fallow, useless, but also fecund. He wondered if there were any wild vegetables growing without anyone’s attention and he decided to use the keychain flashlight in his pocket to investigate.

He made his way up the hill, remembering that he’d called it terracing when he’d convinced Joe and Rita to put in the raised beds. He visited the different plant beds they’d established, pushing through privet and kudzu and wishing jokingly, then earnestly, that he had a hatchet to help him break through the wildness.

Finally, he reached the palapa at the top of the hill. It was too close to the highway, just on the other side of the tall fence and the thick carpet of kudzu that could never quite muffle the sounds of the cars. It was the one downside to their kingdom of a cul-de-sac, that ever-present whooshing noise. But it had made the houses cheaper twenty-five-years ago, when he and Angela had bought in, just a few months after Joe and Rita got their place as newlyweds.

He and Angela had already been married ten years and that had been their second home, the one he had promised her that he would earn for them one day. He’d done it, building up his landscaping company and draining every ounce of energy in his body, but he’d gotten her that house, gave her the home she always wanted. And then, twenty-some years later, she’d sell their dream home without batting an eye, discarding it and him.

It was different for Joe and Rita. They’d gotten married older after traveling the world as young singles. He’d been a commercial pilot and she was a stewardess—she didn’t mind being called that, that’s what it was called when she started after all. They travelled so much, they were so rarely both home at the same time and so he and Angela had looked after their place for them. He helped Rita with maintenance if Joe was gone and Angela made sure Joe always had something to eat if he was home alone. Joe and Rita livened up their lives in return.

And so it had gone, for almost a lifetime.

It could’ve lasted a lifetime, if Angela hadn’t thrown it all away.

*

Early in the morning, light shining through holes in the palapa roof woke him. He squinted, almost rolling over away from the light before he remembered there wasn’t room on the bench. Slowly, he opened his eyes, resigned to looking up at those beams of light.

Joe had fallen a year ago while replacing the palapa roof, his first time doing it alone. This was a bad climate for a palapa, so the two of them had replaced the roof together often. He’d still had his cell phone then, the last vestige of a civilized contemporary life, but it had been held with his other effects during that brief jail stint, and he’d missed Joe’s calls asking him to come by and help with the roof. There’d been one last message from Rita telling him about the accident, and months had passed before he’d been able to listen to them and know what his absence had wrought.

He sat up stiffly and looked around. He’d made a bed on one of the benches with the stack of waterproof cushions that lived outside. The interior of the palapa was still mostly dark, shaded by the untended invasive plants. It was private and mostly quiet, except for that whoosh from the highway. It hadn’t been his worst night’s sleep in the last few years, not by far.

He went outside the palapa and found a mostly clear vantage so he could look down at the house. It wasn’t far away, but it wasn’t close, either. The terraced hill was thick with overgrowth and he thought that he probably wouldn’t be visible from here, or from the second floor of the house either, if he made his way down. It was easier going than last night, once he discerned the path he had made. A couple of ripe tomatoes had fallen from their stems, but hadn’t yet rotted and he ate them like apples, juice dripping down his chin. They were perfect.

He never did knock on the door and ask Rita for the tools. Instead, he’d washed up at the truck stop, then hired onto a work crew outside the Home Depot. That had been two days of work, enough for him to buy a cooler and some groceries. It hadn’t been all that hard to unload everything from the truck and haul it up to the palapa – he just had to wait till the gloaming, the time he knew Rita preferred to eat dinner and she wasn’t likely to be near the windows.

He did the same thing with the tools and the bales of treated thatching from the shed. Someone must’ve stored it away again after Joe’s accident. He was able to replace the roof one morning in the dim early light before Rita was likely to be awake. He piled all of the old thatch along the fence, since he couldn’t put it out on the curb. It was another layer of soundproofing between him and the highway, but of course, he could still hear that whooshing.

Over the next several weeks, he hired on to a few more work crews and bought camping equipment at the Home Depot and food and ice at the truck stop. The mean stray cat, the sibling to Joe and Rita’s pet, who’d refused to be brought inside, started coming around for bites of his canned tuna and hot dogs. On days he didn’t get on a crew, he slipped back into the yard and up the hill to work on the plant beds nearest the palapa, furthest from the house.

At night, he was haunted by happy evenings in the palapa with Angela and the Chandlers, all the nights they’d drank beer and played board games. The girls had complained that he and Joe ganged up on them in Monopoly and truthfully, they had. It had been instinctive to take sides with Joe against them. There was nothing malicious in it, they were just being cheeky.

As he gathered tools and supplies, set up a home for himself in the palapa, he thought often of a book he’d read that one summer at his grandmother’s house, The Boxcar Children. His simple new life felt a bit like the adventure he’d thought those children were having, before he fathomed the cruelty and sadness that the author hadn’t written into their story.

*

Next thing he knew, it was summer. He hadn’t seen Rita at all. He knew the bedroom faced the backyard, but it seemed that quarantine had thrown her off schedule and she was getting up in the late morning. The blue light of the t.v. filtered through the thin curtains and he knew she was staying up late watching those murder shows Joe always teased her about. He seemed to think it was charming, not ghoulish.

He could imagine that Rita avoided looking up at the palapa because of Joe’s accident and he began to move through the backyard more brazenly. He left the first terrace of plant beds and all of the privet and kudzu untouched, but he began to reclaim all of the other levels between his palapa and the house. Some days, he almost forgot about the house entirely.

But one early morning, he cut his hand badly while attacking a stand of privet. He hadn’t thought to get a first aid kit and he was cursing himself for this oversight when he remembered that Joe kept one in the downstairs bathroom, just through the back patio and off the downstairs family room. That door was almost never locked. Probably no one had used that bathroom for months. And Rita wouldn’t be up for another hour at least.

So he made his way down the hill and tried the back door which was, as expected, unlocked. He went quickly into the bathroom, where he cleaned his cut and bandaged it. He thought of taking a moment to use the toilet, instead of waiting to go at the truck stop later when he washed off. But the dusty, otherwise clean, bathroom was eerie. The house was so quiet and still. It surprised him how badly he wanted to get back outside.

The cat waited for him outside the bathroom door. Her litter box was inside and she looked at him accusingly, as if she could smell her feral sibling on him. Maybe she could.

“Hello?” he heard Rita call and her voice was very close.

He rushed over to the back door, but she came into the family room before he could slip outside. The noise she made wasn’t quite a scream, but louder than a gasp. He turned to reassure her before he thought twice.

“Rita, I would never—” he began, then stopped, the hurt you lingering unspoken.

“Dave?” she asked, her fear replaced by confusion. And then the fear returned.

“I’m sorry,” he said and ran.

*

He stayed away a few days, taking jobs and sleeping in the truck, but of course he went back. He waited till nighttime, to be safe, and was relieved to see everything in the palapa was as he left it.

In the late morning, he was cutting back some privet that had made a break for it in his absence, so he didn’t hear Rita coming up the hill. It wasn’t till he felt that creepy feeling of being watched that he realized she was there. He turned to her and immediately set down the hatchet, so she wouldn’t feel threatened. He looked past her, to the foot of the hill, half expecting police, but he didn’t see anyone else.

“What are you doing?” she asked.

“You have to stay on top of this privet,” he said.

She nodded, as if this was a normal day and Joe would come strolling up the hill telling them the BBQ would be ready soon and asking what game they wanted to play. “When you’re done, wash up and come upstairs, please. I want you to see something.”

Stunned, he watched her turn and head back down the hill.

Since she knew he was there and didn’t appear to have called the cops, he went ahead and finished his morning’s work. He gathered all the privet into garbage bags and instead of lining them up against the back fence, he carried them down the hill and put them alongside the garbage bins. He thought maybe the next day was trash day.

The back door was unlocked, so he let himself inside and washed up, as she’d instructed. The cat watched him from the bathroom doorway and then followed him up the stairs. What had they called that cat, he asked himself as he joined her in the kitchen.

“You got my message about Joe’s accident, right?” she asked.

He nodded. “Not right away. I was—” he paused. “I was away, when you called. I didn’t have my phone. It was months later that I …”

“So that’s why you never came,” she said.

“I would’ve helped him, with the roof, if I could’ve.”

“I need your help now,” she said.

“With the yard? I’d be happy to finish up what I’ve started.”

“If you want,” she said. “But I need your help with Joe.”

She watched him, saw on his face that he’d assumed that Joe had died.

“Come on,” she said and walked toward the master bedroom.

He followed, smelling what she wanted to show him first. He almost ran again, but followed her into the room instead. Joe sat in a wheelchair next to the bed. It was clear he’d been living in that chair for a long time and the smell was emanating from him.

Joe was awake and alert, but wouldn’t meet his eyes.

“I can’t manage him on my own,” Rita whispered. “We had help until a few weeks ago, but I’ve been afraid to have anyone in, since he’s vulnerable. I can’t keep neglecting–”

Dave went into the ensuite bathroom and turned on water in the bathtub, letting it get warm before he stoppered the tub. When he came back into the bedroom, Rita had started to remove Joe’s shirt.

“You have to let him help you!” she hissed at her husband, whose arms went limp.

Dave maneuvered the wheelchair to the bathroom doorway. It wouldn’t fit through, so he squeezed inside and together, Dave and Rita stripped away the soiled adult diaper. Joe hadn’t been wearing pants—too difficult to get him in and out of them, Dave guessed. He was shocked at Joe’s skinny legs, the hale and hearty man he’d known withered down since his fall.

The cat was underfoot. “Bella!” Rita called sharply and Dave thought, of course, that’s what they called the old pampered pet. She followed as Rita disappeared with the dirty clothes and soiled diaper. Dave leaned down to lift Joe into his arms. He cradled him carefully as he stepped to the filling bathtub.

“You should drown me like a cat,” Joe whispered pitifully.

But Dave lowered him gently into the water.

As he washed his oldest friend, he remembered being a young husband, when his son was small, the giggles at bath time. He had been home a lot in the evenings, since landscaping tended to be early morning work. Those were the happiest times of his life, he could see that now. Nothing would ever compare to those evenings, caring for his child with Angela. He knew he was forgetting how exhausted he’d almost always been, how irritable, how frustrated Angela already was, but he didn’t want to remember that the roots of all the bad times were already planted in those glorious moments.

Joe was watching him cry, he realized, and he swiped at the tears on his face. “I’m sorry I wasn’t there, when you were fixing the roof.”

“It’s not your fault,” Joe said.

“Maybe if I hadn’t—” Dave started, but didn’t know what to say. Maybe if he hadn’t gone to jail, Joe wouldn’t have fallen? Maybe if he hadn’t hit Angela that one time, he wouldn’t have gone to jail? Maybe if he hadn’t been a drunkard, he wouldn’t have hit her? Maybe if he hadn’t lost his child, he wouldn’t have started drinking? He’d been taught that that was dangerous thinking. He was responsible for so many things, but he couldn’t control anything.

Joe gripped the sides of the tub as Dave washed his hair and squeezed his eyes shut as if Dave’s touch hurt. He thought again of his son, who would squeeze his eyes shut just like that before he submerged himself under the water and came up spluttering, laughing.

“You should drown me,” Joe said again, whispering.

Dave resented the interruption. It had been too long since he’d thought of his son without grief clouding the joy he’d once felt. One of his hands cradled the back of Joe’s neck, holding it above the water as he kneaded soap brusquely into Joe’s scalp. He wondered what would happen if he released Joe’s neck. He’d probably be able to hold his head up above the water. Joe wasn’t helpless, so Dave would have to hold him down, not just let him go.

And he understood why Joe kept saying to drown him, understood why he felt useless now that his legs didn’t work. He was trapped in a multi-level house with just a wife who couldn’t physically maneuver him into the bathroom or the bed, trapped in a wheelchair that probably couldn’t fit through any of the doorways or roll smoothly on the carpet. All of the inventions of the civilized world, all of the home aids and insurance, that would’ve otherwise made Joe’s life better and more normal, were inaccessible.

Dave gentled his touch, in case he was being too rough. Just then, Joe’s eyes popped open and they looked at each other, unblinking. It wasn’t a staring contest, there was nothing to win here. Just the two of them seeing each other.

*

Rita told him he could move in downstairs, if he stayed to help with Joe. The family room had a big screen t.v. no one watched anymore. There were lots of blankets and pillows and a very comfortable couch. The stack of games that they had all played during so many good nights sat on a bookcase by the back door. And he had his own bathroom, of course.

But the comfort of the family room, the house, didn’t feel right, not anymore. Not after all the nights in jail, the halfway house, the shelter, his truck and then the palapa. He’d slept so many places since he last had a home.

He did stay. Each morning, he started the day maintaining the vegetable beds and cutting back kudzu and privet. At midday, when it got unbearably hot, he went into the house to clean himself up and then he took care of Joe. And then, every night, he slipped out the back door, sure in the dark as he went up the hill, like the nameless, feral cat that wouldn’t be brought inside.

Emilie Staat Strong received a BA and an MFA in creative writing from LSU and moved to New Orleans to work in the film industry and wrestle with a novel for more than a decade. Her essay “Tango Face” won the Faulkner-Wisdom nonfiction prize in 2012, “Holding on When I Should’ve Let Go” was published in Et Alia’s Scars Anthology in 2015, and “The Passenger,” was published in Gris-Gris Magazine in 2019. In 2020, she wrote the scripts for a short-form tv series on Instagram called “Love in Quarantine,” produced and co-hosted a political podcast called “Civics, Y’all!” and wrote this story. She’s currently writing essays, pitching a true crime podcast and developing a tv show called “Emergency Contact.”

The Tunnel of Love

At night the subway smells like hot piss. Beneath that, there’s that smell only a tunnel could have: an earthy mix of dirt, oiled metal, rat turds, and still air. There’s absolutely nothing romantic about this place, yet a few yards from where I am sitting, I clearly see a guy down on one knee proposing to his girlfriend. She jumps up and down ecstatically. I take it that’s a “yes.”

Lately, I’ve been seeing a lot of proposals around The City. Just last week while I was eating at this wing spot down in Moreland Heights, I heard the guy at the next table having this conversation with his girl:

“You know what? We ain’t getting no younger. Let’s do the damn thang!”

“You really want to get married?”

“Yeah. Why not?”

It was the kind of proposal that put me in the mind of that Jagged Edge song. I imagine getting old is as valid a reason to get married as any other. Dude didn’t even have a ring. He just kind of sprang it on her, as if he had just figured it out himself. Everyone in the restaurant applauded except me. I had a wing in my hands, sauce on my lips, and a plate of gangsta (fried hard as hell) flats that demanded my immediate attention.

Then there was the proposal from a few weeks back. I was coming out of Njoku Books uptown, and right in front of me on the sidewalk, this guy in a pair of cargo shorts and flip-flops drops to one knee on the grimy ass sidewalk that runs the length of Garvey Street. His girl said yes, too.

The craziest proposal I ever saw, though, was when I was in midtown, and just as I was walking across Langston Square, a bootleg flash mob broke out around me. And you guessed it—it was another proposal.

It seems like everyone around me is getting engaged, but my own love life is nonexistent. Tammy shot me the deuces roughly a year ago. We had been dating for a little over two years and had lapsed into this easy flowing deal, where the romance dissolved beneath old ratty t-shirts and sweats, socks with holes in them, and a scarf that never seemed to leave her head for anything except work. Even the sex felt like we were both furiously masturbating in an effort to get back to whatever was on the TV. We probably shouldn’t have even been in a committed relationship, but we were both too lazy to just call it what it was: fuck buddies, or as these kids like to refer to it, friends with benefits. One morning I woke up, and she was gone—no letter, not even a nod like “later.” She was just in the wind. Two fingers peace.

Since all of that went down, it feels like the universe has had it in for me in the love department. I occasionally go out on dates, but they don’t go anywhere. The conversations are stale, and there’s no real chemistry. One woman kissed me so hard she chipped one of my teeth. Another one loaded me with so many hickeys that my co-workers dogged me for a week. (“Dude, what are you, an eighth grader or something? Who the hell gives hickeys anymore?”) Someone trying to scare off every other woman on the planet, that’s who.

I just gave up. I don’t even try anymore. I just do me. There are more than enough books and movies out there to keep my life interesting well into my gray years.

I watch the now engaged couple boo up on the wall, as they wait for the train. I feel nothing as I look at them, no sense of envy or jealousy, no sense of longing or the wistful remembrances of a love in the fall or the sweet scent of jasmine and mint juleps in the spring beneath the canopy of some tree out in a meadow. I honestly believe that part of me is simply broken at this point, assuming I ever had it to begin with.

Out the corner of my eye, I catch a glimpse of an older, dapper dude in a sharp wine-colored suit, a feathered fedora tilted on his head. He seems like the kind of guy who strolls through spots with a soundtrack playing in the background to announce his entrance. He looks entirely out of place in this subway tunnel, but he is walking directly toward me. He looks familiar, but I can’t quite place where I have seen him before. His eyes never leave mine as he strolls, his body tilting so hard I think he might just tumble onto the tracks. He takes a seat directly next to me, although there are several other free seats.

I start to stand and walk away, but he holds up a bejeweled hand to stop me.

“How does it feel?” he says.

“What’re you talking about, man?” I say, now standing to leave.

“Sit down, young blood. I need to rap with you for a second.”

When I don’t move, he adds with a flourish of his hands, “I come in peace.”

I can’t place where I’ve seen him, but curiosity, more than anything else, causes me to sit back down.

“So how does it feel?” he says, subtly motioning a finger in the direction of the newly engaged couple walking hand in hand now at the end of the subway platform.

“You lost me.”

“You did that, young blood,” he says to me.

“I did what?”

He smiles. “You ain’t figured it out yet, have you? The proposals you keep rolling up on are happening because of you. You never stopped to consider that?”

“Man, if you don’t get out of here with that nonsense.” But it was too late. My curiosity was stoked, and he knew he had my attention.

“Love is love. People can dig each other and whatnot, but sometimes they can get in their own way. That’s where we come in. We clear out the filters.”

I shrug, still lost. “Whatever you say, man.”

“Young blood, I’ve been doing this job for thirty years now. I’ve hooked up some of the greatest relationships of our day, but alas, my time is up. Now it’s your turn.”

“My turn to do what?”

He opens his palms in a gesture suggesting I should know what he means. “You’re a descendant of Oshun, just like me. She was the Goddess of Love way back before your ancestors made it to this country.”

I look at the man and shake my head. “Dude, whatever you have smoked must be some powerful stuff!” The only reason I don’t walk away from him is because I’m too amused to leave. The train is late already, and there is nothing else to do but watch a rat drag a half-eaten cheeseburger into the shadows beneath the platform.

“Just listen to me for a few minutes, and I’ll be on my way. I swear.”

“A’ight,” I say reluctantly.

“You and I,” he says, waving his long fingers back and forth between him and me, “we are descendants of Oshun, the only ones who can bring people together like this. I held it down for the longest, doing my part and all. Then I came across you. When I saw you last month at that Bodega in Garden Hills, I knew you were like me, pulling people together, too. That’s when I decided to pass along my magic to you and give you that added boost. So I bumped into you as I was leaving out the store.”

I try to remember seeing him at the store, and after a moment I can see him, sans the pimp wardrobe, walking out of the store.

“You don’t have to believe what I’m telling you,” he says, “but you’re going to see a ton of marriage proposals for a while. I just thought I would hip you to what was going on.”

While everything he says sounds completely preposterous, there is a part of me that can’t entirely dismiss it. I don’t want him to know that, though. “Yeah, man. Whatever,” I say, even though my bravado is already fading.

He flexes his fingers and examines his rather long fingernails.

“So what’s up with that outfit?” I ask. “You look like you’re headed to the Players’ Ball or something.”

“Well, when you’ve been doing this as long as I have, you start to develop a style with it. These vines are for special occasions.”

I smile. “So you are headed to the Players’ Ball then.”

“Actually, I’m suited and booted to talk to you.”

I try to stifle my laughter, but I’m unable to. “I don’t know whether to be honored or scared.”

“Joke if you must, young blood, but once upon a time a dude walked up to me and laid this same speech on me. I didn’t believe him at first, even though I knew deep down that he was laying it on me straight. I was just some funky zero who couldn’t keep a woman around for nothing. I was like ‘why me?’ but it just was what it was.”

I think about my own love life for a moment. “So I’m supposed to be alone?” The question probably comes out more urgently than I intend.

“That’s the way this works. To help others connect, you have to give a little of yourself. At the end of the day, there’s nothing left in the tank for your personal life.”

I shake my head. “How ironic.”

“I don’t know what you call that, young blood. Thems the breaks. It ain’t personal.”

Now that I’m actually humoring him, I ask, “So you should be able to find someone now, since you’re retiring and all, I’m guessing.”

“We shall see. The soldier still salutes the flag, know what I’m saying. The rocket still has lift off. Maybe my time will come. I know if I see yo ass one day, I’ll be set.”

I laugh again. “Well, I guess I’ll have to find you then.”

“You do that, young blood.”

I am suddenly filled with thousands of questions I want to ask him. My imagination has started to play with the idea of being a modern day Cupid.

“This has been good,” I say. “I thought I was going to be bored waiting on this train, but you’ve made my night.”

“Well,” the man says, rising to his feet, “you have a good life, young blood.” He struts towards the stairs with the easy air of someone with nowhere to be and then slowly ascends the stairs, up and out of the train station.

The train comes thundering through the tunnel moments later. I rise to my feet, replaying the strangeness of it all in my head. I don’t know if I believe it, but I don’t not believe it.

But then I shake my head. Who am I kidding? Oshun? Please! I can’t believe I am actually allowing myself to buy into this for even a second.

Taking a seat in the back of the train car, I notice two guys seated closely to each other. They are sharing an embrace, when one of them removes a small jewelry box from his pocket and opens it. The other responds with the same joy I have come to recognize over the course of this month.

I’m still not convinced any of this has anything to do with me, but I guess I haven’t totally ruled it out either.

Ran Walker is a lawyer-turned-author of twenty-three books. He is the winner of the Indie Author Project’s inaugural Indie Author of the Year Award and the BCALA Fiction Ebook Award. He teaches creative writing at Hampton University and lives in Virginia with his wife and daughter.