by Lloyd Wallace

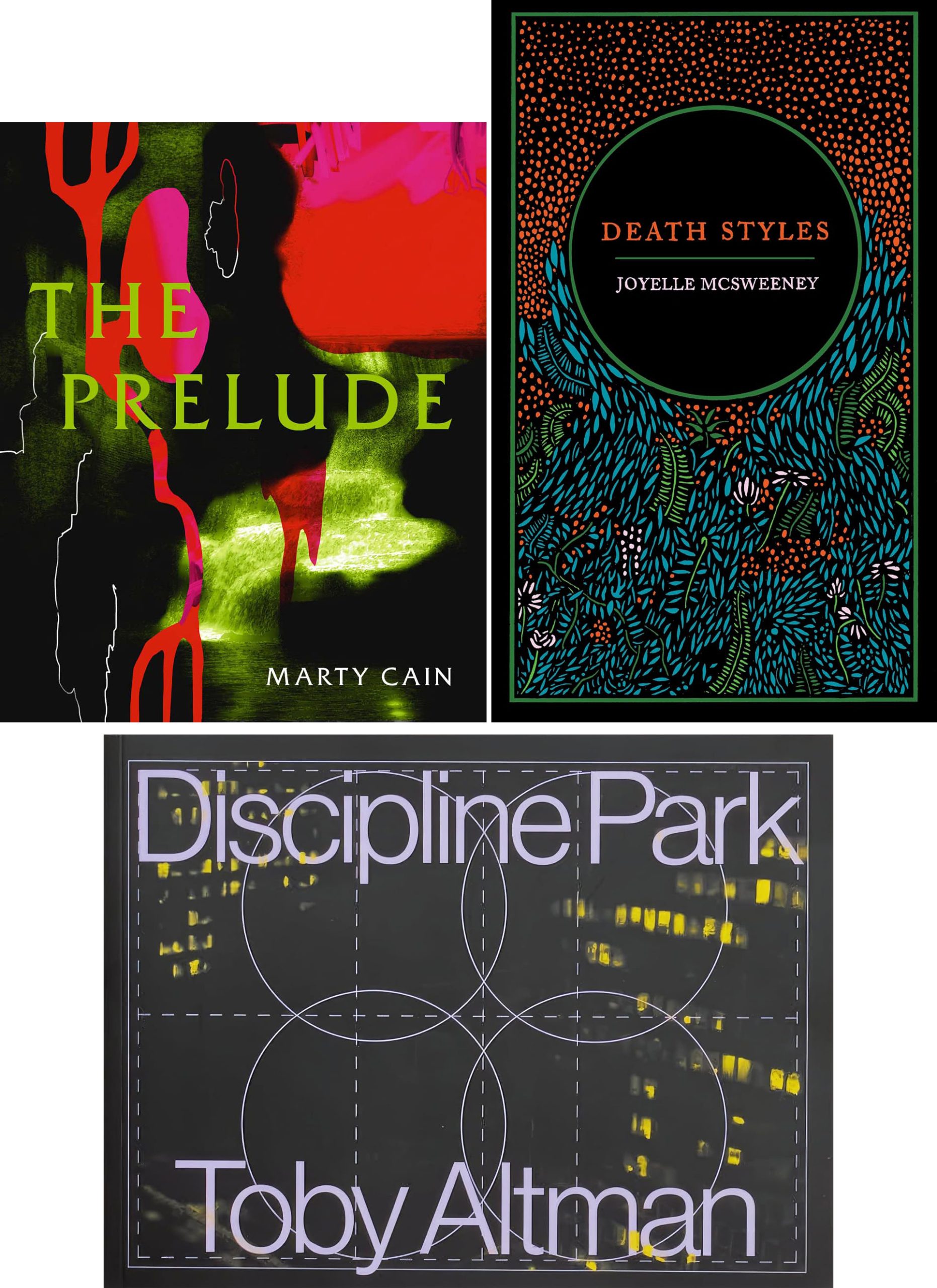

The Prelude, by Marty Cain. Action Books, 106 pp., $18.

Discipline Park, by Toby Altman. Wendy’s Subway, 112 pp., $18.

Death Styles, by Joyelle McSweeney. Nightboat Books, 136 pp., $17.95.

In what ways can a poem reach toward utopia? How, exactly, in a literary culture that all too often reproduces, rather than resists, the broader cultural technologies blinking day and night above our heads—in other words, a culture that rewards, all too often, passivity in the face of institutional power—can one produce a piece of art that might install some noise into that moneyed silence? Can art be the nail, hammered into the present, on which the future might be hung?

The three collections reviewed here all have their own answers to such questions. Whether Cain’s attempt to create something so volatile, so various, it cannot be assimilated into the state, or Altman’s book that is, in his own words, “a demand for another world,” or McSweeney’s set of stylish, love-stubbled resurrection rituals, all of these projects are interested in the ways in which one might build—through the work of poetry or otherwise—more livable, permanent futures, both for oneself and for others.

I

The Prelude, Marty Cain’s third collection, is a book with a various past. Partially a revivification of Wordsworth’s own The Prelude, partially an overheard text—in an epigraph, Cain tells us the book is one half of a conversation with a local creek (“Over time, I learned that the creek had an unconscious… This is what it said to me.”)—and partially a record of lived details from both his own childhood in rural Vermont and his current residence in Upstate New York, the book has many sources. This book also has many mouths, and many faces, many different kinds of bugs beneath its skin. If the book were more plural, more full of different tones, species, and textures, it would probably begin to reproduce in the reader’s hands.

At its (leaky, charnel) core, The Prelude is a “Necropastoral”—to use a term popularized by Joyelle McSweeney—project that denies the existence of state-enforced borders between urban and rural, creation and destruction, and even life and death. Unlike Wordsworth’s own version, which speaks often of the “purifying” power of “Nature”—i.e. of Nature as a discrete realm where one can mine for wisdom as one might mine for ore—and which also posits constantly the “self-sufficing power” of human solitude, Cain’s book is not interested in purity, and in it neither urban nor rural environments, nor individual speakers, ever truly exist on their own. Here, everything is more than just “connected.” Everything is inside everything else. If you are on this Earth, alive or dead, you are collaborating in a muddy ongoingness. You are never not touching the world.

In the book’s second poem, “Every Living Thing Replaces the Absence of Every Other Living Thing,” we are plunged into this wet necro-system from the very first detail:

The omnipresence of violence—of digestion, of hunger—in all aspects of Earthly existence is one of the truths sinewing this collection together. One thing the normalized tone in this passage (note the straightforward reportage of each fact) emphasizes is that there is nothing really abnormal about these images. Such grumous reality is everyday—is everywhere, and every-when. And that includes one’s backyard garden. Even in a luxury condo, one is sleeping with the dead. Just because you haven’t noticed the blood on the pillowcase doesn’t mean it is not there.

This many-textured feasting, this sense of constant, ruinous upheaval, is also reflected in the form of the poems. The just-quoted poem continues:

The book is full of this sort of activity: jagged interruptions, sudden changes in volume, one vining phrase overtaking another, that one brought down in turn by some new overflow of sound, sense, or image. And how else could it happen? As the speaker is changed by his surroundings, as the borders of his body are overrun by bosk, the poem, too, is forced to change. It has to shift from measured couplets, with somewhat regular habits of punctuation, to a form that morphs—grows mushier—as the speaker begins to sing in tune with the dirt-chorus around him. How could it be otherwise? What else would be true?

And Cain’s insistence on cutting up, and re-thinking, all manner of common human boundaries does not stop at those inherent in poetic form. Cain’s longing for language—for life—without enclosure extends to the form of the book itself. Later in the first section, he writes:

This is not a self-defeating gesture; it is not even a gesture toward defeat. It is Necro-poetics made physical, made bladed: by removing the structures that keep the product in your hands “whole,” by cutting through the borders between the book and the rest of the world—and, therefore, the lines between reader and author—you allow for a space where “meaning” and “obliteration,” rather than living in opposition to each other, can instead combine like two frayed rivers to gurgle out a greener song. The quoted poem finishes:

What follows is a rectangular image of what most looks like, to me, TV static, but could also be read as a kind of overlapped root system, or a notebook packed with doodles, or an extreme close-up of the pressure-jellied surface of the sun. The point is: it is not emptiness. And this seems to me one of the book’s more heartfelt arguments: death is not a lessening. And even if it is, there’s nothing dead about a corpse. Let the body’s—or the book’s, or the city’s, or the state’s—cardboard walls fall. The past is still alive in it. Still wriggling, still ready to create a new future.

II

Toby Altman’s collection, Discipline Park, also wends its way through the constraints people place on their environments—and vice versa. The first in a series of three books that, as Altman lays out in his interview with Joe Milazzo for the CSU Poetry Center’s Full Stop, “…attempt to translate the formal principles of [a] structure or [an] architect into poetic principles,” Discipline Park takes as its main subject the work, and words, of Bertrand Goldberg, the Chicago architect who, among other buildings, designed Prentice Women’s Hospital, the hospital in which Altman has born. (Ironically, it was torn down in 2014 by Northwestern University, where Altman was employed at the time.)

Every poem in the book, every double-page spread, involves three things: at least one image of a Goldberg building; at least one piece of found text, often a quotation of Goldberg himself; and at least one passage of Altman’s own, original writing, which blends invention with research, perception with politics, and ideas with imagery.

If reading top-down and left-to-right (which one does not have to do here, as the building blocks into which Altman organizes his material are spread out across the page), the very first thing one sees in the book’s first section, titled “Mandatory Fields (a memoir),” is a photograph of Prentice Women’s Hospital being prepared for demolition. The photo is spliced from a National Historic Preservation video documenting the demolition process, and, as the section goes on, we see the demolition actualized—every page, in this first section, presents a picture incrementally further along in the demolition process until, finally, we are left with the empty lot in which the hospital once stood.

Just under that first photograph, the poem opens into text:

fig. 1. I want to write an essay on scarcity. To describe the city as an effect of deletion or decay: a shadow, a graveyard, a series of imaginary islands. I would begin, for instance, with the graves in Lincoln Park. I would say how the park was stripped of its corpses to make it clean and safe, a place where money stays. Or I would write about Daniel Burnham, who asked the city to build a harp of garbage in the lake. Who has time for that? I too live on trash. A woman’s face with an orange price tag on it. $7.99. A book of coupons. Wild onion collapsing in the throat. And what if the meek refuse to inherit?

These first two moves, the inclusion of photographs—which themselves are focused on another art form, architecture—and the gesture toward non-fiction in the immediate use of the words “memoir” and “essay” let us know what kind of space we’re in: this book is a zone of deconstruction, a place where genre, like concrete, is fungible. A place where the rubble of conventional, even oppositional, artistic thinking—where aesthetic lines are drawn like borders, and art forms, and even individual styles, fight to remain enclosed—is liable to be refashioned into newer, and more habitable, places to live and dwell.

Throughout the book, the photographs and the textual material maintain a curious—I mean that in the best way—relationship to one another. In the first section, as we see the hospital being torn down in the photographs, we also witness an “I” being built in the text. And as we see this statue of a speaker chiseled into being, we are also made to breathe the dust of all he isn’t: all the ways that lack—the presence of absence—has shaped his life. On the opposite page from fig. 1 is the following passage:

I want to write about the city as extension, delay, a limb that buds from the body of the police. To argue that architecture transforms sound into substance. I would say, “We are all sheltered in suffering noise.” I want to ask, as elegantly as possible: “In what does human life consist?” And I would give a savage answer: it is a traveling wound, which inflicts itself on the landscape. As a child I was taught to draw an object by fleshing the dark around it. In this way, I learned to think of the body as a luminous institution, an unmarked space where money travels. I want to ask, “Is a world without scarcity still a world?” And then refuse to answer.

Like Cain’s book, this one is, in many ways, a catalogue of human and non-human relationships, a stretch of skin—or concrete—identifiable by the ways it’s been scarred. And in the same way that a cop’s stray shot might pit a building, might leave behind an emptiness, or a “lack” in a city’s budget might imprint itself, in the form of decay, on the buildings the budget is supposed to upkeep, we are also made to witness all the ways that such indignities might hollow out a human life. On the next page, fig. 2 describes this empty coexistence in detail:

fig. 2. I ate alone at Potbelly and I was not nourished. I watched the institution demolish the hospital where I was born, unfolding as it goes into the raw open, unfathomed wound, and I was not nourished. I watched it again, and I was not nourished. At the time, I drew a small monthly stipend from the institution, and yet I was not nourished. I fell on the ice and my shoulder caught me. The fall lingered in my shoulder, a stuckness that would not nourish. In fact, the wound advanced through the house until it became hard abundance of leaf. Still, I was not nourished.

Throughout the book, intrigued as I am by Altman’s stated aim to “to translate the formal principles of [a] structure or [an] architect into poetic principles”, I was tempted to read this symbiosis—between city and state, between ruler and ruled—as itself a kind of strange translation. Here, every point is a meeting place. Wherever the state touches the subject, an emptiness occurs. And this hole, this small, blank page, becomes the place where history is written. When a man moves through a moldy building, a place the state has wounded, and is made to breathe its spores, his lungs become a record of that relation. They become a place of dark translation. They are filled with a horrible text.

This brings us back to the question of the exact relationship between Altman’s chosen images and his textual materials. Could it be said that the text here is a “translation” of each image? Not just written in response to them, but actually meant to change them, to take the absences that they imply and produce, from them, a “hard abundance of leaf”?

Tempting as this is, I don’t think translation, as a metaphor, can fully describe the linkages between text and image here. In the book’s third section, titled “The Institution and Its Moods,” the pictures, taken by Altman himself, are of a series of fourteen different Goldberg buildings, all of which Altman traveled around the country to meet. And if the textual material shares some formal qualities with the images with which it is paired, which is often the case in this section, it is, I think, because they share a source. To me, that means they cannot be separated—one does not come before the other. They are both the outgrowths of that hour when Altman and Goldberg’s architecture touched. They are the living record of that meeting; they are the marks on Altman that the building left behind. Or, if it is true that one can “draw an object by fleshing the darkness around it,” then maybe this book is the darkness, and, by reading what it does not touch, we can see those marks that Goldberg, and his work, have made on Altman’s life.

But let’s go back to the beginning. In what ways does this collection engage with the concept of utopia? How might one come to heal, or attempt to heal, that “traveling wound, which inflicts itself on the landscape” made by humanity? Altman supplies his own answer in the book’s long “Afterwards,” written in 2019, according to the poet, two years after the completion of the previous sections. He writes: “At its heart, this is not a book about political economy or institutional critique. No. This book is about love.”

Throughout the book, many of the quotations borrowed from Goldberg gesture to the architect’s own somewhat utopian beliefs, the idea “that design could, through cheap, ubiquitous materials, make human life more bearable.” And this is where Altman joins him. In the final pages of the “Afterwards,” Altman writes that he “…wanted the book to become an aggregate instead of an object. A compound substance, sedimentary. I wanted my writing to take on the quality of concrete, the undigested sediment carried within it. Its difference, its resistance, giving the structure strength.” He writes, “I wanted to make this writing more incomplete.”

We soon learn that this incompleteness, too, mirrors Goldberg. The book’s final paragraph reads, in full:

Goldberg is a failed figure—a figure of failure. He hoped his buildings would make life under capitalism more bearable, more human. They did not. But Goldberg’s failure reflects. It has the luminous silver of a mirror. And the boundaries, the frame, the limits. The avant-garde of his period, and mine, haunted by its limits, its incapacity to drive meaningful political change. Take his buildings, then, as a cry: of exuberant anguish. A demand for another world. If this book joins his cry, extends it, offers it to the present, it also joins his failure.

And that’s what the “Afterwards” does. While it leaves the book less “complete,” less polished, it also leaves it fuller. To borrow Altman’s term, it leaves it haunted. By its limits, by its outlines. The “Afterwards” is, in some sense, the book’s shadow. It trails the book—a small, pet emptiness. A beautiful, darkened reminder of all the things the collection is not.

III

Joyelle McSweeney’s Death Styles, too, is haunted by incompleteness. The book’s own Afterword makes the incompleteness explicit: after the loss of her newborn daughter, McSweeney says, “I wanted time to not just stop, but to repeat. Even if I couldn’t have a different ending, I wanted to have those thirteen days with her again.” Thus began the writing ritual that created Death Styles. In McSweeney’s words:

I set myself three rules. First, I had to write daily. Second, I had to accept any inspiration presented to me as an artifact of the present tense, however incidental, embarrassing or fleeting (these are identified as the subtitles for the poems). Third, I had to fully follow the flight of that inspiration for as far as it would take me. I had to tolerate the poem for the time it took to get it down.

The poem as a thing to be tolerated, an uninvited presence, like a crick in the neck, maybe, or a song stuck in one’s head, or an interloper one must invite into one’s home and feed until they’ve had their full. It’s tough not to be reminded of Baucis and Philemon, the old married couple who, after inviting disguised-as-a-beggar Zeus into their home, were rewarded for their hospitality by being transformed at death into a pair of intertwining laurel trees, and thus given a future without apartness. A death that grew into a life.

These poems, I think, accomplish something similar—they stylize death, and the present’s constant vanishing, until it branches into new life. But how do they do that, exactly? In terms of “style,” the poems mostly make use, in the book’s long first section, of one-line stanzas that move at the speed of thought. It is a quick form, and the speaker moves quickly. One can see the utterance, the present, disappearing as it’s spoken. And still, the poems are wet with reality—with presence. As an example, the book’s first poem, “8. 11. 20”, begins in this way:

I found myself thinking often, reading this collection, as flush as it is with uber-present imagery, of Pierre Reverdy’s idea famously referenced in Breton’s Surrealist Manifesto regarding what makes an image “strong”:

The Image is a pure creation of the mind. It cannot be born from a comparison, but from two realities, more or less distant, brought together… The more the relation between the two realities is distant and accurate, the stronger the image will be—the more it will possess emotional power and poetic reality… An image is not strong because it is brutal or fantastic but because the association of ideas is distant and accurate.

I would like to ask: could not the same idea be scaled up and applied to the structure, the composition, of a poem as a whole? That the more realities a poem contains—the more full it is of hours, spotted grasses, distant emotional climates—the more potent it might become? I think it can, and I think that is the strength of these poems: their ability to press realities together. To make of time a medium—a long, blank, stretch of canvas—and to scrunch it up, forcing every inch of it to coexist, to come into wet contact. “All times are noon,” the poem says. And this is not just a poeticism; one thing the unpunctuated, slippery motion of the form allows is a constant swishing from the present into memory. For example, later in the poem:

From there, the poem returns to the more settled lyric “now.” So, to state my previous point more clearly, though these poems make use of the present that the title of each poem references—and which the daily writing ritual grows out of—past events, and people, constantly intrude. As the poet tolerates the poem, the present tolerates the past. These “lost” moments bulge constantly through the membrane between the past and the present—almost as if it isn’t there. As if the poet has erased it. As if “the present” is just the name we give to that part of the past we can still touch.

In 2022, the journal Annulet published a précis by McSweeney (whose subtitle, in part, calls it “a guide to parenting your live and dead children”) that ends with the following words:

How could I sum up the work of this book any better? A poem is a kind of survival. When I look at these poems, though they are made of what is now the past, what I see is the ribboning future. A kind of expansion. I’m reminded of a line by the poet Mark Leidner: “Believing in God is like believing in an endless stream of letters following Z.” Do I believe in God? I believe in these poems. They are, if you ask me, endless. They are additions to the world.

Lloyd Wallace is the Managing Editor of Poetry Daily. His writing appears in Iowa Review, Poetry Northwest, Washington Square Review, and elsewhere.