by Thomas Calder

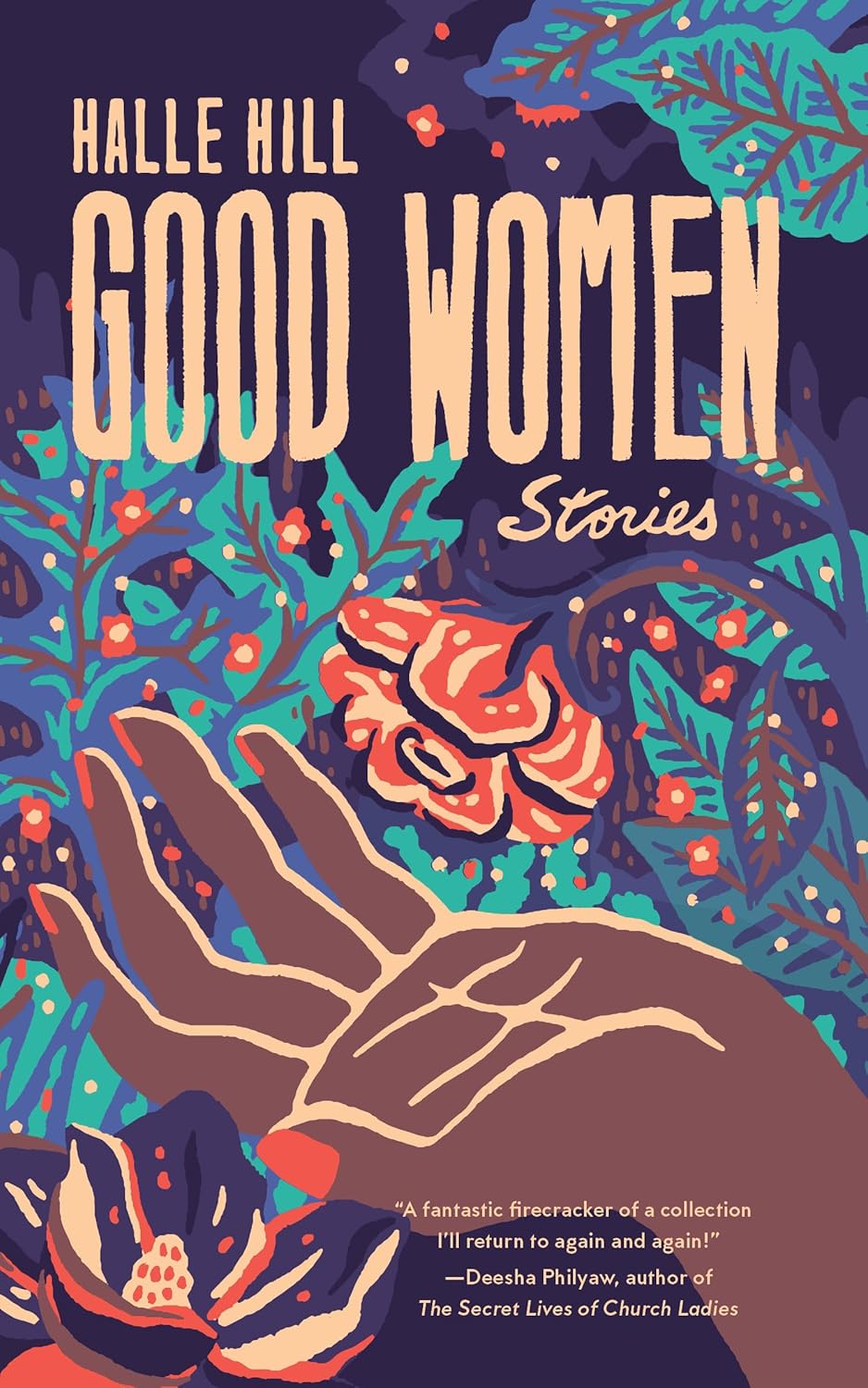

Good Women, by by Halle Hill. Hub City Press, 216 pp., $17.95.

“Seeking Arrangements,” the opening story in Halle Hill’s debut collection, Good Women, immerses readers in an intense all-night Greyhound bus ride from Nashville, Tennessee, to Boca Raton, Florida. The story’s narrator, Krystal, a 27-year-old college dropout, is in route with her new boyfriend, Ron, a white 50-year-old convalescent with a weak heart, a satchel full of medications and a tendency to call Krystal his “mutt” and “little hot thing.” The two met, Krystal explains, “on a dating site for wealthy men and twenty-something women.” But as the bus rolls out, readers quickly understand what Krystal is either unable to see or unwilling to confront: the person she is traveling with on this 22-hour journey is likely a fraud and she only has four allotted stops between Nashville and Boca to figure this out.

The story is a perfect introduction to a collection populated by Black Southern women struggling to understand themselves, the world they inhabit and the people they share it with. The scenario also establishes one of Hill’s greatest talents as a writer: an ability to tease out tension within mundane settings. This gift reappears throughout much of the collection, without becoming a liability or crutch. Instead, readers are brought into familiar places—an Outback Steakhouse, for example—where class divisions between relatives is revealed during a family reunion (“Her Last Time in Dothan”). Or they’re delivered to less frequented locals—a county fair, perhaps—where a hapless teenager working a dead-end job stumbles into an opportunity to unleash retribution on her mother’s abuser (“Honest Work”).

Throughout Good Women, Hill also takes unanticipated and revealing turns in the midst of emotional and traumatic moments. In the book’s closing story, “How to Cut and Quarter,” Marjorie, a depressed and lonely 29-year-old, is returning home to manage her deceased father’s estate and attend his funeral. A single child of divorced parents, much of the narrative focuses on her attempts to make sense of her relationship with the recently departed, who served as a pastor for a Seventh-day Adventist church.

In one of her most riveting scenes, Marjorie steps up to eulogize her father. “I took every lesson as a preacher’s daughter and put it to good use,” she narrates. “I had the cadence of a proper eulogy down, the lesser known scripture I’d heard Daddy recite from this very pulpit, well-timed long pauses and just the right pinch of pathos and just enough restraint.” Marjorie’s triumphant recapitulation of her delivery continues in empowering detail. This moment, when compared to earlier passages filled with self-doubt and uncertainty, creates a sense of possibility for someone who is otherwise lost. Her words are not merely reaching the funeral’s guests; she is hearing them herself and trusting what she has to say. “I beamed as I looked up from the podium,” Marjorie notes near the end of the passage. “But everyone looked at me like I was deranged.” Blood, she soon discovers, poured out of both her nostrils throughout much of the tribute.

As several of Hill’s twelve stories reveal, she is not a writer who shies away from the morbid and the grotesque. But she is also quick to delight readers with humor and unflinching satire. For-profit universities (located in the upstairs level of a former Sears department store), sweaty nightclubs, and Weight Watchers meetings are all brought into the fold. Religion, mental health and racism are also turned over in both subtle and explicit ways. Many of Hill’s characters are haunted by their indecisions yet required to act. Some respond more boldly and ably than others. It is the collection’s less definitive endings, however, that linger with readers longer.

For example, back in “Seeking Arrangements,” Krystal is still on the bus by the story’s end, only now she is drunk and reading her horoscope in an attempt to make sense of her future. The lights in the cabin go out. In the darkness, she briefly images a scenario where she escapes. “I know I could get off right here if I wanted to,” she tells herself as the story concludes.

Krystal’s fate likely matches that of Hill’s readership. When you pick up Good Women, there’s little chance that you will escape unscathed. Just as there is no chance that you will enter Hill’s landscapes and language without seeing the story through — wherever it may take you.

Thomas Calder is the author of The Wind Under the Door. His work has appeared in Juked, Gulf Coast, The Collagist and elsewhere. He serves as social media manager for the Asheville-based literary nonprofit, Punch Bucket Lit.