by Felicia Zamora

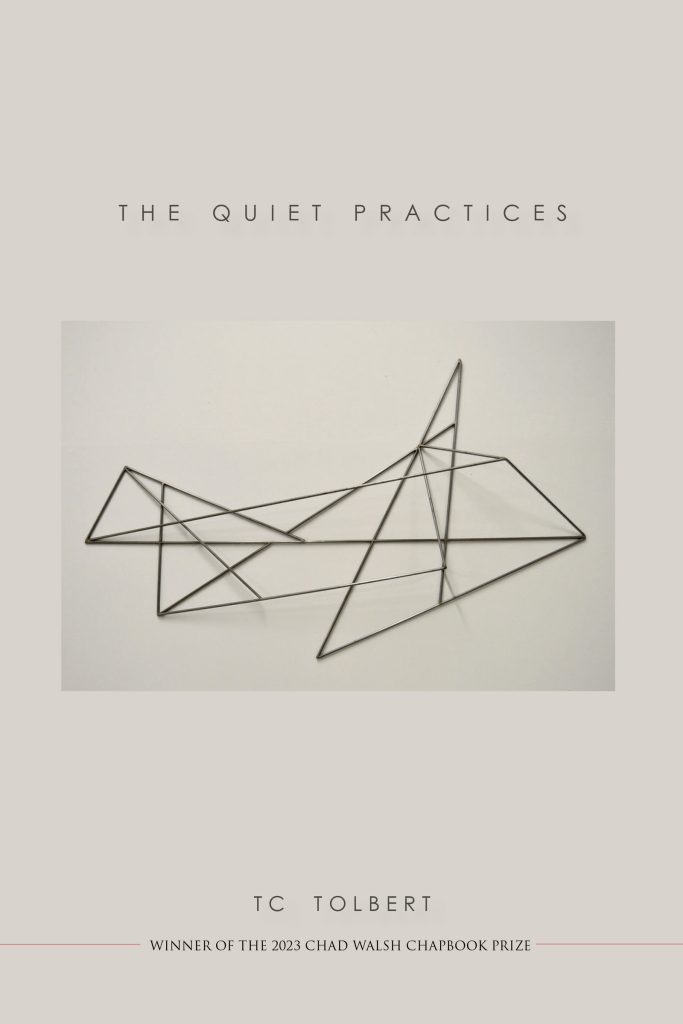

The Quiet Practices, by TC Tolbert. Beloit Poetry Journal, 54 pp., $18.

The capaciousness of we. TC Tolbert’s newest poetry collection, The Quiet Practices, the 2023 winner of Beloit Poetry Journal’s Chad Walsh Chapbook Series, circumnavigates becoming through want, aliveness, the “holy unmade,” hunger, dark matter, the tender spine, “trans prayer,” the unsaid, heaven, “trans boredom,” trauma, “trans sacrum,” naming, “trans baptism,” “trans ovaries,” “trans plasma proteins,” “my trans Melissa, in every iteration”—where a gorgeous chant conjures a world where trans is not only bodily, not only consciousness, not only “interrobangs used unironically,” but trans is all, trans is everything, trans is aliveness. (I pay tribute here to Kevin Quashie’s invigorating and crucial statement, “We are totality,” in Black Aliveness, or a Poetics of Being.) The Quiet Practices is an epistolary love poem to Melissa Dawn Tolbert, “An infinite, inexhaustible rhizome of the heart. You,” where the you is TC, the you is Melissa, the you is a trans voice who, “in order to live, must continue to respond to changes in the lungs.”

The word quiet comes from Latin quiētus, or past participle quiescere, to rest from toil, and late Latin quiētāre, to calm. How lovely to think of a former iteration of the self being laid to rest from work, being brought to calmness through inextricable love— to resist forgetting, to linger in the plurality of all that makes a life and who a person is always becoming in simultaneity. The idea of quiet in these poems dwells in the relational, the intonations of naming where “small/ is not a fair synonymy for soft – naming you I/ have found another way to send my body back/ in time to claim how she wants to be touched.” Nothing in the body remains quiet if we listen. What an act of resistance to name and be named.

The book reads as a singular body that flows in and circulatory to itself—which makes complete sense when considering the intentions of this work—to be imbibed holistically in both micro and macro ways as the body endures and metamorphosizes moment after moment. Epistolic addresses appear throughout the book as moments of breath, like a filling of the lungs, for instance, “Dear Melissa –,” “My Melissa,” “I’m afraid, of Melissa,” “Imago Dei,” “Dear ,” and “in our lifetimes.” These gorgeous inhalations give a moment of pause, providing a soaking-in effect. With formal and linguistic acrobatics, Tolbert queers the page in deliciously ungravitational ways, where our reading cannot remain hinged to the vertical stare, the left justified counter-impulse to the mess-and-gorge of human existence. Long lush lines sprawl and reach across the voids of space in this book, forcing the reader to turn the book horizontal, to feel the turn of self as self, where contrapuntals, indentions, acrostic spines, and hidden textuals transform to blurry demarcations of (un)stability in trans existence. Lines become greyed-out subtextuals, as in this passage: “Poem in search of comfort—” and this one, “tracing the boy I/ see his mother – in her hand out-/ lined under us both,” where polyvocalic urges echo in the poems: the voice just beneath the voice.

In the visual poem “T,” Tolbert exudes possibility on the page, prophesizing all the T’s in one’s orbit: a name, “prayer to,” “thigh held,” “part of,” “a knot,” “sight,” “hurt in her body,” “strong enough,” “under this cover,” “tending,” “a shot I,” and on and on where the constellation of T becomes the gravitational force of the voice’s ever-expanding experience. Beginning testosterone injections, the voice emerges as a catalyst for possibility, for abundance, for mourning of the missing, and to “teach me” as it diagrams the nuances that compound in life-making. Much like dark matter, these poems crave acknowledgement, yet not necessarily knowing—where to be known feels like an inaccurate act, as the uncovering, the searching, the becoming feels most palpable.

Space is a place of surrender in Tolbert’s poems. At one point, an arrow points upward from the text “the body” toward “had been written” and I am smitten by this writtenness next to “surrender/ unreserved.” How do we supplicate to time, to the past, to the person we were when in a state of wereness? How does a person embody supplication without hesitation, without doubt or worry or terror? Tolbert controls space—dare I say, empowers space—to fight against hesitation into an ocean of arms and love to carry the thinking into “hymn-loose and match-hungry and storm-bought” incantation. Trauma and violence subtextually gasp in these worlds, but Tolbert’s voices resist reductive monolithic thinking as they lean deeply into breaking apart binaries.

Language becomes a vehicle for shattering. The poem is the mechanism “To strengthen. In the mouth”. The poems circle us back to the power of naming over and over again. The softness of the lips, the mouth, the tongue, the epiglottis, the lungs where speech forms. The calling in of authorial presence and the intimacy in which these poems reverberate deeply throughout the book, but no place as poignant and necessary as:

Tolbert reminds us how we tie to language and how language allows us conception of—thoughts, instincts, becomings, imagination, seeing, being seen, hungers, and hereness. It’s in the unsaidness that Tolbert wonders when a word dies. Can we resist a word so long that it haunts? Tolbert refuses graves for words, refuses namelessness by saying here. The last line of the book is the hidden voice, greyed out as a shadow, “saying here means I I knew longer than not.” The double “I I” in repeat. The weness of the double “I I,” the everythingness. The double “I I” as the duality of self, where hereness lives in relativity to the words running down the middle of the page, smashed together, another spine, “nowalwayshasbeen” as a hymn for the self leads us into the penultimate stanza, the stanza that burrows into my chest cavity, knocking on my breast bone, “there is no heaven/ like a body born/ of its own hunger.” Mic. Drop. In The Quiet Practices, hunger is a prayer and Tolbert answers: Here.

Felica Zamora, a contributing editor of this magazine, is the author of seven books of poetry, most recently Interstitial Archaeology, which will appear in 2025. She is an associate professor of poetry at the University of Cincinnati and a poetry editor for Colorado Review.