by Corey Van Landingham

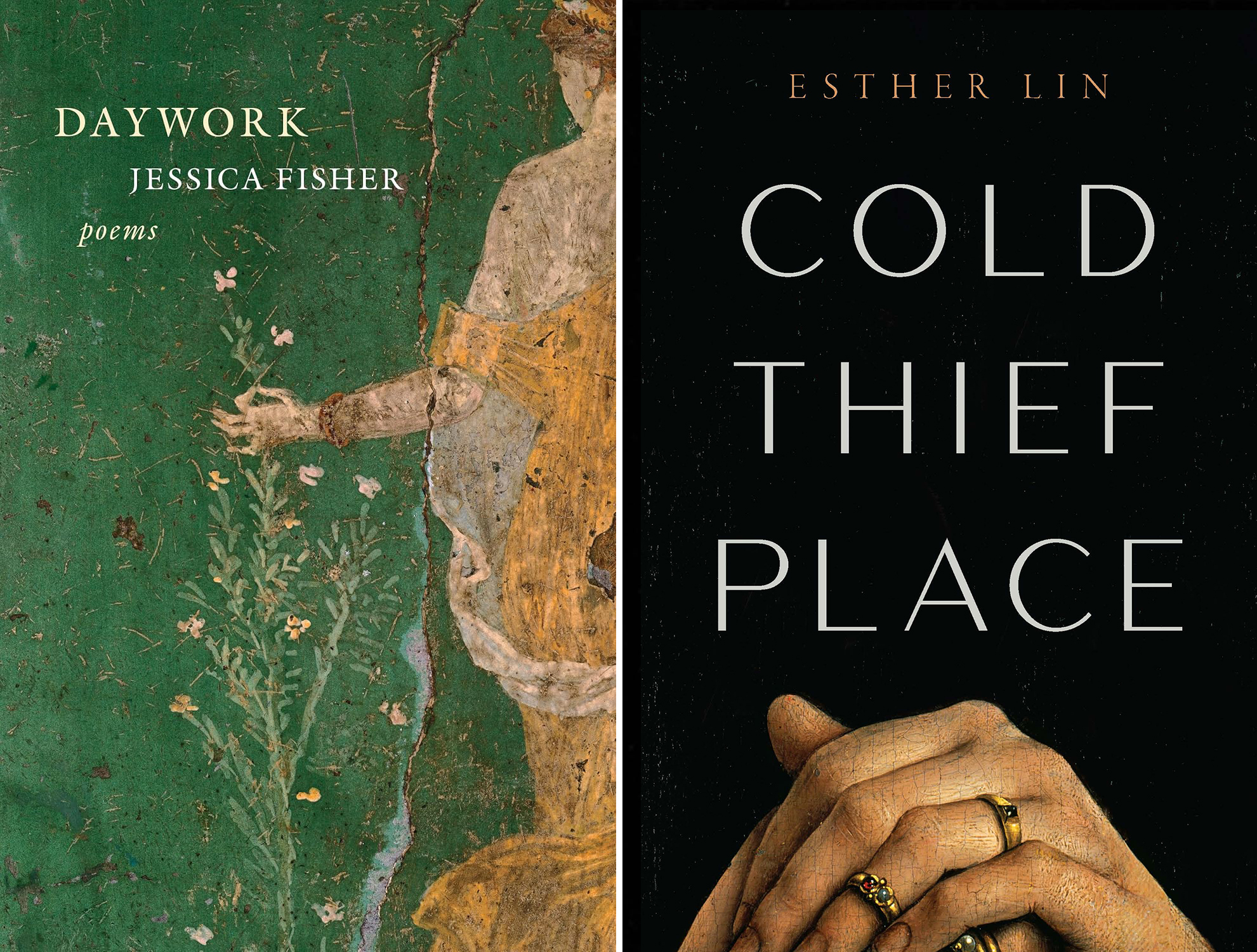

Cold Thief Place, by Esther Lin. Alice James Books, 65 pp., $24.95.

Daywork, by Jessica Fisher. Milkweed Editions, 82 pp., $16.

I

It is not particularly original to state that literary movements—and their attendant literary styles and proclivities—are often born from reaction and opposition. Nor that literary history is cyclical, doubling back on itself, rearing once again the values and aesthetics of the past. I think of a literary movement or school as something like an ocean: added to, evaporated, diluted over time, but ultimately the same body of water, just appearing in different places, washing up new objects on distant shores.

Which is to say that I could spend the entirety of this review tracing the origins and distortions and returns of the style with which I’m particularly concerned here: what I’m calling “the spare.” But—and in obeisance to that subject—a brief, and woefully tidy, gloss will have to suffice.

There are many ways that one can encounter poetic spareness, some of which I will touch on with the individual books below, but perhaps the most obvious iteration is the kind of unadorned economy brought about by the Imagists (reacting, in part, against the various excesses, the sweeping emotional scale, of the Romantics and the pretensions and abstractions of the later Genteel tradition). Influenced by the clarity of Japanese haiku and hoping to diverge from an era of literary decadence and artifice, the Imagists were invested in the pared-down essence of image, in the “wet, black bough” and “white / chickens” and sea irises “painted like a fresh prow.” Pound’s excited letter to Harriet Monroe, accompanying poems by the then-emerging H.D., might be seen in a workshop letter today: “It is …. Objective—no slither; direct—no excessive use of adjectives, no metaphors that won’t permit examination.” And really there is no avoiding the Modernists, whose values many of us have received by osmosis via the New Critical rehearsals of self-containment so persistent, despite some examination, in the workshop today.

One could talk more of the Objectivists. Or, going back in time, of classical Chinese Lüshi forms, or of ancient Greek epigrams. One could talk about the sonnet (there is never enough room to talk about the sonnet!). One could trace the various styles and schools from which the spare poem has continued to swerve: the indulgences of the confessional; the (re)emergence of the book-length poem, and the porousness of the poetry “project” spinning out from documentary poetry; the chattiness of Ultra-talk; the popularity of the braided narrative poem. One could opine on the ways social media has fostered the propagation of the short poem—what can be displayed, in toto, in 1080 x 1080 pixels (a friend of mine suggests that this is the reason behind the recent renewed popularity of Linda Gregg’s trademark short poems). In suit, one could talk about (and I’m really sick of talking about) the various modes of contemporary distraction and the resulting comfort and apparent ease when encountering the spare poem.

I hope instead to offer a more specific look into how two recent books embrace, use, renew, and depart from these various lineages and influences.

II

The spare does not just mean the brief. When I teach a unit on “The Spare” in poetry, I do bring in short poems, but I also ask students what else can be considered spare in a poem besides its length. One of the most productive conversations results from our reading of and discussions surrounding Layli Long Soldier’s long poem, “38.” While at first students are somewhat baffled in considering a five-page, long-lined poem to be spare, they’re quickly convinced of its tonal spareness, its related wariness of adornment, and its adoption of the matter-of-fact discourse of the seemingly-objective, which is—as the poem progresses—revised, scrutinized, and destabilized in Long Soldier’s decolonial historical poetics.

Tonal spareness can come across as a kind of mastery. There is the potential assumption that to have removed various excesses, a certain clinical distance must have already been maintained by the poet.[1] Perhaps this is part of what makes some of the quintessential spare poets appear as almost vatic presences—to be able to see the future, one must be disconnected, in some manner, from the present. Louise Glück rules this realm, this mode, and the Imagists’ desired hardness, the crystalline thingness of the poem, is often achieved more through attitude than through image in much of her work.

Esther Lin’s debut collection, Cold Thief Place, shares in that Glück-like sense of intensity. There are lines here that feel like they could have appeared, say, in The House on Marshland, like, “her future held before her // like a cool glass bowl” (“Wuping, 1969”), or this ending to “A Book About Dragons”:

If in the work of some poets tonal spareness creates the effect of command—that clinical mastery—or the matter-of-fact distance won from authority, in Cold Thief Place Lin creates a manner of proximity instead. As the speaker records and imagines her parents’ flight from Communist China and their ensuing path to Africa, Brazil, then America, the poems refuse to linger in any moment for too long. Early in the book, it’s almost as though the gaps in these narratives lead to a collapse of distance, an inability, in the moment, to put everything together into a whole. The poems are almost overwhelmed by what they cannot hold, what they cannot know. This perhaps sounds like a critique of the poems, or their perspective, but it’s really the opposite—an admiration for the engaging journey of the book, which feels as though it is undergoing, as it unfolds, a process of navigating distance. “My sight is unclear,” the speaker claims in one poem rehearsing family myths (“I heard this story again and again”). The collection’s early poems are full of questions, full of fragments. “What to do?” “Who knows what single women thought?” “Red Guard. Red tape. / What facts. What luck. / A Xeroxed photo in my desk.” Some elide punctuation, unsettling the distinct separation of phrases and creating a kind of choppy, nervy accumulation of semantic meaning as the poem adds on, breaks, progresses.

In contrast, here’s a poem from the last third of the book. It’s called “Reading Madame Bovary.”

Though the death of the speaker’s mother is introduced in the second poem in the book, what changes by the time we arrive at “Reading Madame Bovary” is the speaker’s ability to move from the more fragmentary pieces of her mother’s life (and of the difficult and violent life the speaker faces with her mother) toward this cool appraisal seen in the poem’s ending. That final line, “Today I am without mercy,” not only marks a temporal distance, but an aesthetic distance. This sober statement requires that distance. Part of the complexity of this poem, and the book at large, is how the viewpoint constantly changes, and, with it, the speaker’s understanding of both her mother and herself.

Lin’s unflinching portraiture resembles some marriage of Gwendolyn Brooks and Sharon Olds—their clarity and their intimacy. In a longer, multi-sectioned poem revolving around the death of the speaker’s mother, “The Ghost Wife,” the speaker, her father, and her sister—who has just returned from unplugging their mother in the hospital—watch “the latest zombie program” together:

That final sentence is one of the most sustained moments of description in this book—Lin often prefers short shards of imagery. But even here, the zombie-wife is portrayed with a kind of loving economy. Her loveliness comes through the concrete details and the crisp working of the imagination through the simile.[2] The zombie-wife appears to us vividly through the life-that-might-have-been. One of the markers of Lin’s poetry, however, is how what is absent haunts what’s present. Though the image is from the television show, it clearly evokes what isn’t seen by the speaker: her mother’s body.

This may be one of the many ways Lin’s poetics of spareness operate: through a manner of chiaroscuro, or a kind of vision test. While what is present in these poems is finely wrought, deeply affecting, it is often the lacunae that stand out. Part restraint and control, part refusal. But also—and this is where, as a reader, I become deeply invested in how the spare operates throughout an entire collection—part procedural, working like memory, asserting the bright flash of the known amidst the murky gaps of time, trauma, imagination, myth. In much of Cold Thief Place, these gaps work as a form of lyric movement (“She said, // You can’t know how bad it is. / Bovary’s daughter worked in a satin mill”). At times, though, the spareness of these poems too much precludes movement. In “First Snow,” for instance, the poem revolves around one scene of the speaker and her siblings seeing snow for the first time. The tension of the poem arrives near the end, with the collision of expectation and reality. The expectation is for the snow, and for the family’s new home, to be beautiful: “The beautiful country. / That’s what the Chinese call America.” But the reality is that “it was mostly mud.” Still, in trying to appease their mother, the siblings attempt to build a snowman, and the older speaker of the poem concludes that, in their matching winter coats and their “disbelief,” they “must have appeared odd.” Other than presenting a vivid scene, not much happens, or changes, between the beginning and end of the poem. There must be a way for spare poems to allow for both understatement and (despite my wariness of the phrase) epiphany, for a sustained moment in time to emerge, somehow, out of itself. I find myself missing, here, the more elliptical, laconic style, where what is withheld illuminates and leaps and unnerves.

It’s important to mention, though, that the tension between presence and absence isn’t solely one of style. In “Illegal Immigration,” the final poem in the collection, the title bleeds over into the opening lines: “Is the absence of a paper / and the presence of a person.” The gaps, the returns, the varying perspectives and effects of distance are all crucially linked to the experience of an undocumented speaker living in the United States and her attempts to piece together her parents’ lives—fleeing authoritarian China, arriving at a new dogma of religion, settling in a foreign country where each moment carries the threat of I.C.E. showing up at the door. Even what originally seems to be a “safe” decision—a green card marriage with “a nice boy”—carries its own threats to the formations of a stable life.

The condensed nature of these poems and their direct statements lead to what I can best describe as the unsentimental. But I don’t think that’s exactly right. The composed tonal realm of Cold Thief Palace, with all the distances collapsed and achieved, is one that strives toward a more sensitive perception of oneself and the lives of others. As Lin writes, “I see her best // when she’s half-hidden.” This is a refreshing debut, one that reasserts a place for the nuances of control in a contemporary poetry landscape that too often privileges its opposite: the ecstatic, the wild, the righteous.

III

Jessica Fisher’s Daywork derives, as the author notes in her acknowledgments, from a year spent in Rome, whose landscape and histories are evident—with frescoes, Pompeii’s brothel, stone castles, and “the rubble of empire.” Instead of the central figure that Rome may have played in another poet’s book, here the city is backdrop. In the foreground stands the endurance and precarity of art, making and motherhood and beauty in the face of violence, dreams and parables, an obsession with edges.

It’s that very obsession that first captivated me and that invited more meditation on how Fisher works with, and within, the sphere of the spare. Because in Daywork, the spare is not just one of the modes in which she writes. It’s also a subject—something courted, but also something scrutinized.

“Only so much description can do,” Fisher writes in “After Empire,” which appears in the last section of the book. And later in the poem, “Beauty had an end / Where it ends something opens.” In another, “What I was taught is that art excludes.” It isn’t surprising, in a book titled Daywork—referring to the Italian term giornata, translated as how much of a fresco can be completed in “a day’s work”—that so much is self-referential, verging on ars poetica, focusing on the edges of what art can, and chooses to, depict. The spare poem is acutely aware of the limits of the frame. It may seem obvious to emphasize this curated nature of poetry, but reading through any number of recently-published books might have one wondering just how obvious such curation really is.

In one of the poems that seems to me the least likely to be considered spare—“Camera Obscura,” which extends more into immersive scene and description and relies less on the spaces between image and thought, less on quick pivots—the speaker recalls the titular classroom experiment. In it, the teacher has the students attempt to draw the candle whose flame is reflected through a pinprick in a piece of cardboard. The students struggle: “When we traced the flame / in our lined notebooks there was no way to / indicate that it was alive, hot.” The poem ends with a larger lesson, though, one reaching beyond the classroom:

In a sense, the pinprick feels like a poem, especially one pared down, the seemingly small space that can both reflect and distort the world. Fisher pushes the potential metaphor even further than this, though. If the flame reflected on the wall is “abstraction,” then what is held behind the students’ closed eyes might be considered something closer to art, or the perception of art, that which is transformed through individual vision. That which lingers long after the real flame is blown out. That interior pinprick like an imprint, working from the edges of what is fleeting to something that endures.

A similar image is reflected later in the collection at the end of a long poem titled “Night Song.” In it, a speaker sees a saw-whet owl caught in a net for tracking. “Under black light, I felt / the rapid heart beating / in my hands.” Then the owl is released, and, like the flame, the image of the owl remains:

Other correlations between subject and mode can be found in the numerous prose poems in the book. Outside of those that use multiple airier, one-or-two sentence strophes (like Quan Barry’s in Controvertibles, or much of Saskia Hamilton’s All Souls), prose poems, in their claustrophobic accumulation, don’t often immediately register as spare. Fisher’s prose poems operate in the world of stories, dreams, fables, fairy tales, and parables. One of the long prose poems is even titled “Parable,” signaling that something has been condensed in order to gesture to something larger. In another, the speaker dreams of the little match girl. Though she has not thought of the figure in the fairy tale for some time, “in that cabinet of the mind she must have remained, waiting.”

All these poems, circulating around images that become, or have been, inscribed into the eyes and the mind, have reoriented my thinking of the spare. Previously, I had loosely grouped spare poems into two categories: the provisional and the oracular. The former uses the mode, whether in a poem’s visual structure, its syntax, and/or its elisions, as a kind of epistemological indicator—impossible, to include, and to know, everything. The latter, in its vatic nature, sees around its edges. It is stable, sure (or at least adopting a tonal certainty). It has carved away the excess because it knows what belongs at the center. These poems range from those of Glück—that I-have-been-to-the-Underworld-and-am-here-to-tell-you hardness—to those of Lucille Clifton, for whom the oracular is caught up in a kind of faith, one which knows there is something “beyond the face of fear.”

Fisher suggests an alternative to these groups. Or maybe it’s a fusion, as she connects the that-which-can’t-be-known of the provisional to the that-which-endures-certitude of the oracular. Those flames the students carry with them, that character from a long-ago-encountered fairy tale, the “something” that lingers after the owl is released—these merge stability and mastery with mystery and transition. These can only trouble a speaker, and reader, because of their firm, durable images. In a way, parable breaks down here, or is at least complicated. Instead of the tidy conversion to legible moral, a portion of something, a pared-down story, doesn’t offer answers. This is where the poet’s fixation on edges reoccurs—like in Cold Thief Place, what isn’t in a poem is nearly as important as what is. In a longer poem revolving around a medieval painting of the Massacre of the Innocents, the speaker dwells on that negative presence: “and the arms that reach / toward absence, how to show it.” Or, as she writes in one of the prose poems, “What you see is never the whole story, of course.”

Elsewhere, the poems in Daywork are more legibly spare in their style and brevity. In one of my favorite poems in the collection, that style merges gracefully, and devastatingly, with Fisher’s preoccupations on absence and impermanence:

Poems in this middle section of the book attend to the death of a close friend, and the elegy appears fundamentally twinned to these contracted poems. If traditional Western elegies manage emotional excess through a kind of modal excess—the tripartite structure of lament, praise, and consolation carrying, in that emotional journey, a desire to capture all the features of mourning—many contemporary elegies negotiate the space of grief through abbreviation. But one thing I’ve noticed about many of those elegies is that their brevity often results in something static.

“Hive,” on the other hand, doesn’t suffer that same inertia; there’s almost an extremity of movement in this poem of just ten lines. The first two lines present a lucid image, the couplet acting like the wax, sealing the image shut. But not quite, for the larvae are hardening, are in the present-tense action of transformation. This creates a dynamic hinge as the poem moves on to the speaker’s children and their worried questions. Instead of answering them immediately, the poem moves to somber meditation: “In the dark room, in the sealed cell,” the parallel syntax chant-like, but nearly whispered. Then the delayed response, which provides no clear answer—“How am I to know?” Another leap, as the poem moves into, as Richard Hugo coined, its “generated subject”—the friend’s illness, and the haunting image of her “honeycombed” lungs. Finally, we arrive at the poem’s largest pivot in the last two lines (fitting, the reference to Wyatt’s sonnet, with the quoted line appearing right before his volta). Here the poem ejects from its primary scene into allusion. We have moved out of the present and the deep past of the sixteenth century court shuttles the poem into a new register. That new register is one of statement, one of rhetoric. The lifted line from Wyatt leads directly into explication—“meaning he could not.” Though there’s a confidence to this kind of exposition, ultimately it emphasizes failure. For the lungs to function properly. For the friend to live. For the speaker to answer her children’s questions. That last line confronts head-on the lyric drive toward immortality. Impossible, Fisher reminds us, in this moving elegy, full of the fluctuations of an organizing intellect.

In another elegiac poem, the speaker, on the phone with her dying friend, attempts to move around the house for a better signal. She looks out her window at a brick wall “soon to be demolished” and attempts to imagine the space “once it’s gone” only to encounter another failure, delivered in clipped fragmentation: “could think only of an absence of brick / and not even that really.” The poem itself elides all punctuation and uses fragments that mirror a kind of unsettling disorientation as the speaker moves around, searching for a clearer connection. Multiple poems in Daywork and Cold Thief Place ditch punctuation, which strikes me as another feature, or technique, of many spare poems. These poems boil down to their essential parts—no punctuation, few conjunctions. This can be quite affecting, as though a poet seeks the fewest barriers of language and grammar. Something so laconic, though, reveals in fact a sense of labor—again, the edges of what is shown illuminating what is not.

But that severe abridgement doesn’t always deliver. “Native” appears in the same section of elegies:

The gestural style—this poem almost like a sketch—can shut down a reader’s imagination, vision, and attention, instead of allowing its incomplete nature to unveil what lies beyond itself. The caesuras here dramatize silence and fragmentation, with white space disrupting the phrasal unit. In addition to feeling a little familiar in its visual format, the poem also verges on the melodramatic: “the voice calling” almost parodic of lyric poetry’s tendency toward self-seriousness. One thing I like about encountering spare poems in a collection, however, is that they remind me a poem doesn’t have to do everything—something sometimes forgotten, I suspect, in the proliferation of workshop poetics. A poem is its own world, but it doesn’t have to be the whole world.

“I wanted to trace that limit,” Fisher writes of the seam of the giornata in the title poem, “to know / where the painter found an edge / and stopped.” Like Pound’s mandate that poets “Use no superfluous word, no adjective, which does not reveal something,” the fine poems of Daywork are, in the tracework they invite, in their persistent awareness of these edges, constantly revealing.

[1] For more on the difference between clinical detachment and aesthetic distance, see Eleanor Wilner’s brilliant essay “The Closeness of Distance, or Narcissus as Seen by the Lake.” In it she finds:

With clinical detachment, distance separates and frees the person from feeling for what he observes. But what aesthetic distance separates us from is not the emotions but the ego. With poetic imagination, it is precisely this distance from the ego that enables the emotional connectedness we call empathy—and because it is remote from ego threat, as we enter imaginatively what is actually at a remove from us, we are given both vision and connection.

And, later, that, “The clinical mind, detached from its objects but not from the ego, looks down on and thinks to master what it sees; oppositely, in the act of imaginative remove, the intellect serves not the ego but the life it illuminates, enlarging what we can see beyond providing protection to what is seen.”

These are crucial distinctions of perspective, but what interests me here, in Glück’s and Lin’s work, are the poets’ deliberate wielding of that clinical distance through the device of tone as its own mechanism, in a way, of aesthetic distance.

[2] Though I’m using an example of simile here, in general I have noticed that within the poetry that I’m deeming spare, metaphor is preferred to simile. The swift, confident alchemy of metaphor allows a poet to elide connective tissue. This being like that is a matter of description. This becoming that, rather than merely resembling, is its own form of movement (in addition to its descriptive capacities).

Corey Van Landingham is the author of three books of poetry, including Reader, I, which was published by Sarabande Books in 2024. A West Branch Contributing Editor, she teaches in the MFA program at the University of Illinois.