by Chelsea Christine Hill

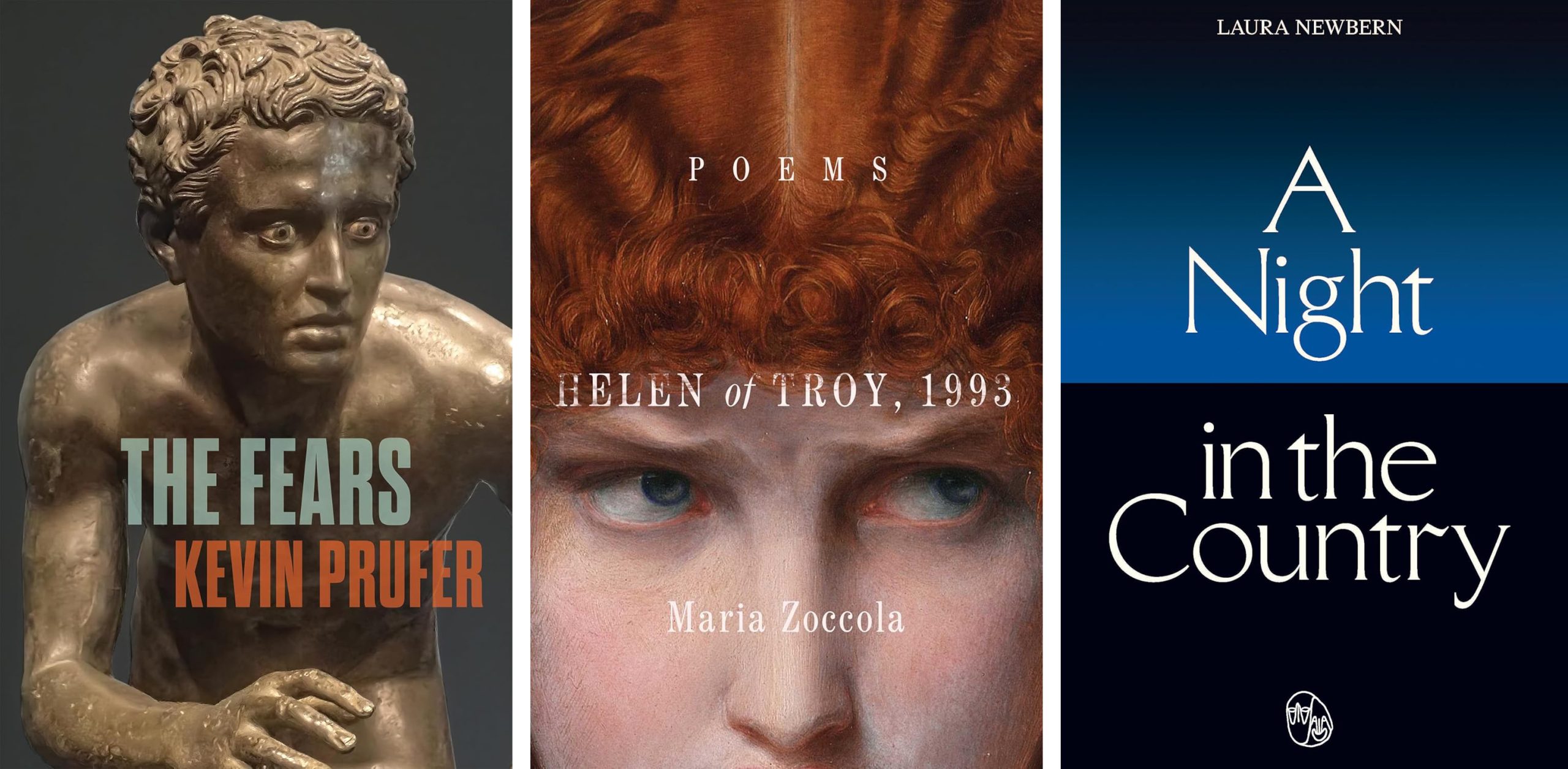

The Fears, by Kevin Prufer. Copper Canyon Press, 83 pp., $17.

Helen of Troy, 1993, by Maria Zoccola. Scribner Books, 96 pp., $18.

A Night in the Country, by Laura Newbern. Changes, 80 pp., $18.99.

Countless times over the last year, I have been reminded of Aristotle’s oft-quoted (or, really, paraphrased) remark from the Metaphysics, “in wonder begins philosophy.” I have spent the last year as a PhD student steeped in philosophy. I have, exhausted, pressed my forehead to lines of Plato, written ham-fisted responses to Kant. I even put a foot in action theory—and almost immediately pulled it out. For a while, I fled back to poetry as a retreat, though I’ve found, more and more over time, as my interests in poetry and philosophy have mingled, that each shares in the other’s concerns.

This became most clear in a seminar on the historical role of wonder in philosophical inquiry. In discussions on Plato, Euripides, Boyle, Bacon, Paré, I slid into the position of the poet in the room. It wasn’t a role I hated, but one that, week by week, pushed me to describe poems, craft, the making of an aesthetic object, as they relate to the practice of philosophy. I was asked if argument runs against the condition of a poem, if all poems must, by nature, render “ordinary language in unfamiliar ways,” etcetera, etcetera. I engaged these inquiries with enthusiasm, whether in class discussion or weekly responses, but, really, I found myself always scrambling to understand my own admiration for poetry, the reasons why I myself must write, and why, importantly, I want others to read and love poems, even in the context of a PhD course.

I’m not here, I assure you, aspiring to a “philosophical read” of poetry, though I believe the intersection (and historic quarrel) between poetry and philosophy is worth study. However, my position between the two draws out the necessary condition of wonder—receptivity, attention, reflection—that the poet and the philosopher share. In his essay “Composed Wonder,” the poet and critic James Longenbach takes Aristotle’s statement as an invitation, a “reinvention of humility, the means by which we fall in love with the world.” Whether contemplating the universal or the particular, the state of wonder sets off new ways of seeing.

As I progress quarter-by-quarter through my doctoral studies, I return to these questions often. And, conversely, I desire a way, as a poet, of mediating the space between learning and poetry without writing from the position of concepts. The books I’ll discuss here, from Kevin Prufer, Maria Zoccola, and Laura Newbern, do not render language wondrous through visual gymnastics or expansive experimentation with shape, but through poems that, more often than not, conform to the well-established shapes and line-work of poetry’s canon. However, these collections, within the context of their learnedness, their own acts of reflection, threw me, this year, into a position of humility.

I

“Creon’s error is remarkable,” opens Prufer, “when viewed as confusion / about the proper placement / of the living and the dead.” The Fears, Prufer’s ninth collection, wastes no time with an oblique opening. It is a book that demands attention to its entries and exits, the portals of learning, of death, and of thinking itself. To continue with the first poem, “A Dog Barking into the Night,” we find ourselves in the language of logic, an if-then resignation that immediately sets the collection’s tone:

Placement is an existential matter; it is, in The Fears, a concern of the living and dead, but also of language and the line. From the beginning, in the (often harsh) breaking and movement of line, we see “placement” as a function of thought. Prufer continues:

Rather than conceal the poem’s associative seams, the movement of thought—the placement of two events side by side—becomes a feature of the collection’s larger concerns. “A Dog Barking” immediately brings us into the world of The Fears, peopled with fathers, rulers, friends, and strangers now gone. The crossing of one thought into another is often a step in or out of a distant history, now collected in books, and into the speaker’s present situation. The use of the “+” sign, now standard in Prufer’s work, “turns over” thought to this end. I cannot help but recall the heart of our English word verse, from the Latin versus, used for both the turning line of the plow and of the poet. Verse is a thing that, through the line, shows the mind’s turns.

The progression of thought, indicated by Prufer’s “+,” brings to mind, too, the mechanics of thinking, the material situation of our bodies, and even our written work: firing neurons, words that arise and fill what was once a blank page. Another example from his opening poem:

He returns to “thought” many times in The Fears as a generative, human activity, in the brain and on the page, that stands in opposition to void or absence. He tells us in “A Distant Row of Black Pines”:

This, I’m sure, seems rudimentary. Yes, good images think. Yes, thoughts, of course, make images. What I mean, though, when discussing Prufer, is that we see a meditation on craft beyond the ars poetica, a reflection on the act of writing that not so much makes a case for what writing is like, but attempts to enact and interrogate the ticking gears of the writer’s mind. In other words: we see the act of writing brought into dialogue with our material (embodied or, perhaps, mechanistic) reality, a process that is human, and therefore mortal.

Mortality, the essential human condition (think of that textbook syllogism: “Socrates is a man, all men are mortal …”), finds expression in image, the placement of one thing by another, but also in the syntactic details. In “A Dog Barking,” we see not only the snaking of one idea into the next stanza/section, but a trick of doubleness Prufer so often creates at breaks. In the poem “brother and I” / “stood on the porch smoking” is juxtaposed with a similar, though not identical, break in the following line, “Our father was in the hospital / dying.” There are two modifiers at play: there is “smoking,” and there is “dying.” The stark line break is a plainspoken moment concerning the father: he is alone in his clause, apart from the brothers, dying. He was nowhere else—and, like the dead Antigone, is nowhere. That is, for Prufer, the condition of death, and one that he articulates through the poetic line.

Such issues of placement accumulate meaning in Prufer’s reflection on the creative act. Placement is a kind of form: occupied space, something placed, made into a thing; but, we know, made things are subject to decline. Immediately following “A Dog Barking,” we encounter “Body of Work,” which brings death—human death—into dialogue with artistic obscurity. “I have failed,” he writes, “to consider my own / eventual complete / negation”:

Making shape, setting form—these actions create monuments, books. But like names on a weathered tomb, form loses shape, its language loses meaning. Prufer interrogates the desire to memorialize our lives via deeds, a goal shared by writers and emperors; it is a task seen in the running list of names in Roman histories or memorials (and isn’t a tomb, too, a memorial?), or even the Wikipedia pages for writing prizes. Reflecting on such lists, Prufer writes in “Ants”:

Like the human body, the body of work sinks into that “nowhere.” Obscurity, falling out of fashion or history is (or is another kind of) dying. A memorial, a prize, or a marble bust all commemorate past events, and what we face, in The Fears, isthe writer’s effort, as expressed in “Absences,” “to preserve the intricacy of [his] own mind / against the eventual / certainty of [his] absence.” Consider also the moment in “The Fears” where Prufer’s subject, the writer of “this poem,” thinks of his own work:

For Prufer, action is the only answer to the certainty of future absence. Though obscurity, too, lurks alongside death, there is a comfort, even if a small one, in Rilke’s distant words: our works may fall into that obscurity, but there is power in the act of writing through that fear. And though Rilke, I’ll note, might one day fall into “nothing,” there is a balm in seeing, one hundred years later, our present writer remember his words, write them into his own poem. The train eases “into the blackness,” that is certain, but the speaker falls back to his own work.

This is the work of The Fears: to take“action against fear,” a fear that, if we allow it, keeps us from the task of making art, though the artist must confront that “dark passage” of thought, the tomb, the history made “a pile / of brick and glass.” I do not wish, however, to say this book is simply an apology for the “redemptive power of art.” Prufer shows us enough times that art, like us, fades, but he also, I think, shows us the value of human activity, of engaging the faculty of thought. To return to the opening poem, Prufer delivers there one of the collection’s most unsettling and well-wrought moments. After we see the father, like the frozen dog, “be[come] an animal, too,” his “claws / curved around the remote control,” Prufer takes us down this tunnel:

This is, for me, one of the book’s best moments—the moment where I most marveled at our human ability to mold image from words, to conjure thought on the page. In that last line, Prufer moves to the iambic, the cadence of voice: a moment of the recognizably spoken word, but used, strategically, as a means of transformation, the hand to “claw.” Though we see Prufer use this image earlier in the poem, here he drops the euphemistic veil of simile. The animal-like condition of his father’s death is, for the speaker, just animal. The image gathers its power, though, in the contrast of the human hand joined with the claw, a compassionate act of reading—a distinctly human action, which is, foremost, the concern of living, and so of the poet.

II

Of Helen, most already know the basic story: she’s beautiful, swan-born, wife of Sparta’s Menelaus, and mother to Hermione. Offered as a prize to Paris, Prince of Troy, by Aphrodite, she leaves or is kidnapped by him (sources disagree), and finds herself in the doomed city. Her face launches a thousand ships. A long war ensues. Maria Zoccola’s Helen of Troy, 1993, the latest release from Scribner’s poetry imprint,retells Helen’s story in a fantastically-rendered 1990s Tennessee. As Emily Greenwood, for The Yale Review, points out, we’ve seen a number of Homer adaptations in recent years, standouts including Alice Oswald’s Memorial and Madeline Miller’s The Song of Achilles. With the arrival of Emily Wilson’s translations of The Odyssey (2018)and The Iliad (2024), recent conversations around Homer have noted the oft-neglected and elided nuance of his female characters. Though scholars like Wilson draw out feminine agency via the art of translation, Zoccola reimagines a new world for the ancient Helen, one that allows further interrogation of love and desire, domesticity and place, and how one relates their story.

As Greenwood goes on to write, “[i]n ancient Greek literature, reflections on the inexorable reciprocity of warfare almost always lead back to the myth of the Trojan War and the Iliad.” For Helen of Troy, 1993, there is warfare between private and public lives, and Zoccola’s return to the Iliad is also a well-timed response, I believe, to a growing anxiety over the future of women’s bodies and roles in civic life.

And what does all this have to do with wonder?

Formally, many of the poems tread familiar ground: the tidy blocks of lowercase text, the sonnet crown. I’ll admit that I was suspicious of Zoccola’s “Afterword,” worried that I might find explanations and dense history, when what I wanted—I thought—was to be left, simply, in Helen’s Tennessee. What I found, though, was rich imagination and long-fed fascination with language and learning, a genealogy of thought. “Because I grew up a quiet, book-eating girl,” Zoccola writes, “with unrestricted access to several branches of Memphis Public Libraries, I was well-versed in Greek and Roman myth long before ninth-grade English with Mrs. Bell.” In Helen of Troy, 1993, she does not sing of ships or arms, and certainly not of masculine rage, but of Helen and the “book-eating girl.” It is a collection with an eye toward the political anxiety of recent years, but born of personal history and a consuming interest in reserves of myth.

In this debut, Zoccola preserves the wonder of her childhood encounters; imbued with an expansive voice, her Helen claims the devices of epic for her own story. In the poem “helen of troy catalogues her pregnancy cravings,” we see Zoccola play on the Homeric catalogue, her speaker eschewing ships and armaments for “pickles. peanut butter off a spoon. that cereal / with the little blue guys on it, the gnome things in hats.”

Concerned with control, and lack thereof, the book shows Zoccola’s speaker assert her agency through the language of war. In the midst of oncoming motherhood, Helen forms statements of her own desires; “i’m trying / to weigh myself down,” “triscuits, i tell him.” And, as she concludes: “i want to break something on my teeth. i want to crush / it so fine the load goes down like abracadabra, / alakazam, watch me make the whole thing disappear.” What Zoccola articulates here is Helen’s appetite for living, until “there’s no need to beg for more.” Her Helen mobilizes language, like a vast armada, as a display of feminine power.

Other poems in Helen of Troy, 1993, too,draw upon the power of successive nouns and clauses—and while the list is, arguably, overused in contemporary poetry, Zoccola reinstates its force. Her sentences often remind me of the pile-up of classical language, the dense, no-guardrails feel of wading through a vast sea of nouns and modifiers, as in “helen of troy goes parking with the defensive tackle”:

Though Zoccola’s text looks worlds apart from an ancient epic, her Helen adopts the winding speech of the ancient heroes. Look, for instance, at that first line’s metonymy: the “militia of orange beaks”!

Reading a poem such as “helen of troy goes parking,” I also cannot help but think of A. E. Stallings, particularly her collection Hapax; in the lineage of Stallings poems such as “First Love: A Quiz,” Zoccola’s Helen reflects on a story of youthful desire and sexual violence but, more importantly, the issue of how we relate such stories back to ourselves. Helen says, “i can’t remember what i wanted. / homecoming, maybe. Prom … his fingers in my hair, bright pulse of pain” and “i thought: i don’t—but what did i know? maybe i did.” Though this poem opts for short, urgent clauses, clipped syntax, we still exist, I think, in the microcosmic quality of the classical catalogue, the magnitude of ordinary objects that embellish our lives. In “helen of troy goes parking,” this quality captures the pieces of memory, such as those after a traumatic event, that swim back to us, that we—in life, in verse—work to bring into harmony, to tell the story of our individual lives.

This microcosmic quality also informs “another thing about the affair,” a poem that revolves around the central event, the affair with Paris (or “The Stranger”), but through a chaotic morning sending Hermione (“The Kid”) off to school. The child’s fish keep dying, “belly-up, all of them.” We are deep in the everyday. Then Helen, addressing her sister, lets loose this sprawling sentence:

Moments like this echo what many consider Homer’s greatest accomplishment: his description of the shield of Achilles, his own meditation on wonder and art. In Book XVIII of the Iliad, Thetis comes to Hephaestus with one request: to make armor for her son, Achilles, fated to die in battle. Hephaestus is more than obliging; he tells Thetis that “any man in the world will marvel at / [this armor] through all the years to come—whoever sees its splendor.” And what he makes is more than armor—it is a world in itself. The shield is brimming with activity: the moon “rounding full … all that crown the heavens,” wedding feasts, a sieged city, pulsing grapes, lions in battle with bulls and their herdsmen. All the rings of life are set into motion on the shield and this is, according to Homer via Fagles “the wonder of Hephaestus’ work.” The effusive quality of Zoccola’s poems and her depictions of human life—visits to Chuck E. Cheese, screenings of Jurassic Park, the morning bus ride— show us what moments, from 1990s small-town Tennessee, might make it onto such a shield.

I could say more about Helen of Troy, 1993—its storytelling, its tapestry of voices, its uses of form from the golden shovel to the sonnet crown; but I want to give primacy to my moments with Zoccola that put me in that state of wonder, keep me flying to my bookshelf, to Fagles, and to Hephaestus, the great craftsman, leaning over his anvil. Reading on the shores of Lake Michigan, from the steps of limestone we call “The Point,” I’d think of Helen, her name passed, in Zoccola’s words, “back and forth / like the builders who raise a chamber in lines of stone.”

III

Winner of the 2023 Changes Book Prize, Laura Newbern’s second collection, A Night in the Country considers as its subject the action of making—and remaking—image. Italo Calvino wrote that at night we “walk abroad using the imagination.” Newbern’s worktakes us on such a walk, where we view a thick forest of cedars, studies by Dürer and Bellini, bodies of reference from Agatha Christie to Tristan and Isolde. Newbern’s search for shape is continuous—and from that she derives the task of the artist.

In a world of, I think, loud poems, Newbern’s meditative lines use slow turns of rhetoric, allowing us to experience, in a quiet space, image working toward its shape. Here, for example, is her poem “Night Road” in full:

Unlike Prufer, for Newbern image is not an “issue of placement” or an eruption of thought, but a series of studies that, by return, reinforces objects against the dark backdrop of night, works toward their solidity. We make many passes by water in “Night Road” and the white church “heaves itself up / out of the ground…” She makes similar passes by her scenery through the poem’s sonic texture, as we read, “the water, / the silent water, which” and, soon after, “where we were, / though we knew well / the body of water.” This runs parallel to the poem’s reflection on “Tristan”/“tragic”; to quote from Louise Glück’s introduction, “the context shifts.” However, like King Mark who wonders before water, shape comes to the surface, but changes under the conditions of light.

“Sometimes my mind goes back to certain things,” Newbern writes in “Black Forest,” “[l]ike everyone’s.” She returns, often, to the land or the landscapes of portraiture. Northrop Frye, in describing the lyric, speaks of a “world-within-the-worldness,” a “summoning” that culminates into the event of a lyric poem. This layered temporality contains its own returns; in “Country Night,” the woods hold not only the story of a ravenous wolf, but a memory of the story as told by the speaker’s grandfather. In another poem, “Sycamore,” Newbern opens:

Though the image of the “bevy of women” exists on the page, it resists definition (“maybe / on the campagna of Rome”). From the ancient land, the countryside before Rome, these women echo out, reach the speaker. They are ghosts.

To return to “Country Night,” “[l]ike a sentence, the poem is half / in sunlight, half in shadow; sometimes cloaked.” Newbern wants to get “behind the black double doors of the house,” as she writes in “Iliad,” to pull back a veil—though in A Night in the Country, the veil cannot remain pulled back. The speaker must take many glimpses behind its fabric, and contemplate, too, the sight as pictured by others. In the collection’s final poem, “The Veil,” Newbern reflects on the (“actual”) last painting of Van Gogh. When the site of a tree’s roots—the painting’s subject—are “unveiled” as a public event, she writes:

For Newbern, I think, this is the exhaustive work of poetry: to engage that world-of-many-worlds, the image that has been the subject of many artists before us, “rendered” already in many hues. But she shows us, still, the artist at work in “the dark doorway … broom in hand, / staring into forever. Oh stock-still. Straight ahead.”

Reading Newbern, I think not of the wondrous shield of Achilles, but of another poetic object: the shield of Milton’s Satan. As Satan takes up his armaments in Paradise Lost, Milton describes his shield as

Unlike the shield of Achilles, Satan’s shield is not a microcosm of the living world, but a reflection, a pensive object relegated to the powers of the moon. As Srikanth Reddy observes, in The Unsignificant, the shield “belongs to that wondrous category of things that hold dual citizenship in the realms of the material and the ideal, like a poem, or an angel, or the venerable moon itself.” The poet looks through the optic glass, like early astronomers, and sketches, over and again, studies of foreign bodies to understand their “spotty” terrain.

Of the aesthetic object—the poem, the book—as a site of reflection, I’ll say that the English word “admiration” derives from the Latin admiratio, meaning wonder, which begets our word “mirror.” When we admire, and so find pleasure in art, it engages the faculty of wonder, and this word cluster implies that some mimetic act, a reflective state, occurs as well. What does it mean then to approach the study of art objects with humility? In the context of craft, casting the “practiced” eye on a poem or text, why—and how—can we continue to wonder as a learned observer? “Objects of wonder,” Longenbach adds, “must remain perpetually unnamable if their power is to be relished repeatedly.”

I close on Newbern because I love best her picture of the learned observer within the state of wonder. Though Newbern surely assigns names, her objects, like the chanting of “they say” or “water,” maintain an “unnamable” power. The speaker of “Starry Night” tells us she did not know her great-grandfather, an astronomer, nor on winter nights does she “know / what is out there”; but for her great-grandfather, she creates “a black car that purred / when he nosed it around the corner,” and for the knowledge of “out there” the body of a book, the cover “navy blue.” Like a self portrait (and there are many in the collection), poetry is crafted with a mirror, though a mirror will only show one angle at a time, one view. “Deeply blue” water seen by day, “black / as a charm” by night, to recall “Night Road.” In A Night in the Country, Newbern approaches her poems with the humility of the artist and the philosopher, who will both, one day, “head for the woods.”

Chelsea Christine Hill‘s recent poetry appears in Copper Nickel, Poetry London, The Adroit Journal, Hayden’s Ferry Review, and elsewhere. She earned her MFA at the University of Illinois and is a current doctoral student in the Committee on Social Thought at the University of Chicago.