Why the Assembly Disbanded, by Roberto Tejada. Fordham University Press, 88 pp., $16.95.

instrumentation for distributed empathy monetization, by William Lessard. Kernpunkt Press, 40 pp., $14.95.

Winter Phoenix, by Sophia Terazawa. Deep Vellum Publishing, 140 pp., $16.

I remember reading excerpts of Niccolò Machiavelli’s The Prince in my Language and Composition course during high school, unsure exactly what I was supposed to extract from the text. On the one hand, there was a clarity to Machiavelli’s language that I found enlightening, that connected me, a junior in a south Texas classroom, to this sixteenth-century treatise on political structures and power. But on the other hand, I understood that it was an instruction manual for royalty, that it was meant for a certain group of people to enforce their will upon others. Even after all these years, the line that has stayed with me the most was Machiavelli’s assessment that “[p]rinces and governments are far more dangerous than other elements within society.” When examining Roberto Tejada’s Why the Assembly Disbanded, William Lessard’s instrument for distributed empathy monetization, and Sophia Terazawa’s Winter Phoenix, it is evident that institutions and those with enough power to affect others on a mass level make Machiavelli’s statement ever more true. In whatever shape or form, poetry has always been political, and there is a good argument to be made that it must never separate itself entirely from the issues and movements of any present moment. Tejada, Lessard, and Terazawa not only remind us of poetry’s obligation to be at the forefront of justice, but to explore ways in which we can make our society a better place to live.

I

Reading the work of Roberto Tejada is both a meditative and thought-provoking experience. Images are prevalent, but it isn’t uncommon for philosophical inquiries to pervade the page, prompting readers to question more deeply how they add practical and symbolic value to their personhood while responding to societal issues (the daily consequences of borders, the nature of global citizenship, political uncertainty, white supremacy) that increasingly take center stage in their lives. While Tejada’s earlier book Full Foreground (University of Arizona Press, 2012) examined identity and selfhood through a more transnational lens, his newest collectionlooks more intimately at our relation to one another through the effects of displacement, capitalism, and the portrayals of the “other” in everyday images and media.

For Tejada, no spaces are off limits to critique. In “American Household,” Tejada looks at the modern American household (by no means a definitive term), and discovers that ultimately, we are at the mercy of corporations and companies that view a person’s home as a business opportunity rather than the sacrosanct space it should be:

Examine the objects, devices, and materials around your house, and a trend will no doubt emerge: we rely on the products companies produce, whether our television sets or our sofas or the medication that we take in private. There is no escaping this, nor that some people and families are at the mercy of what these corporations offer. (Think of the increase in prices, even before the recent influx in inflation, of life-saving medications that people were already struggling to afford.) This inevitably leads to questions about whether we deserve “cash” or “cake,” and regardless of the answer that we tell ourselves, or that others tell us, we are “wait[ing] again our turn in / Line” to achieve a position where we no longer must think about who is cheating the system to get ahead. Extend this past the household, and you don’t have to look any further than the distribution of Moderna and Pfizer vaccines to see the way greed, power, and money play out on such a dangerous level. Government officials at all levels used their power to bump family members and friends in the queue for the jab, even though the vaccine came at no cost to citizens. But, even when things are free, they are not free, and Tejada reminds us that everything comes with a price, regardless of whether it will save your life or merely provide you with a place to rest your head.

Tejada’s poetry often views past and current concepts, events, and situations from a slight distance, one that nevertheless still provides enough perspective to get across its intended meaning. But Tejada’s poetic range is wide, and there are moments here where the first person provides intimate insights into how one is viewed by those in power, as in “Liquid M”:

This anxiety the speaker feels resembles the anxiety one might have felt in middle or high school, that overwhelming sensation of being judged for what you’re wearing or your mannerisms, or really for just being different from other people’s insular expectations. “Liquid M” prompts us to ask ourselves if we ever fully outgrow the mentality we develop in youth. Some would argue that these same bullies are the ones who achieve position of power and whose selfish decisions adversely affect others. As Tejada’s speaker so aptly puts it, they are always “seeking to engage with cruel insight,” always attempting to render others into “Nothing.”

Some of the book’s most evocative images, however, aren’t in the poems themselves, but rather in the photographs Tejada includes in the collection. As Tejada indicates in the acknowledgments page, this book is intended to double as an art book, and the photographs complement its themes: loneliness, the desire for ownership and a space one can call their own, the commercialization of other cultures, of the past. The photographs appear in a group in the middle of the book, a sort of intermission.

In a photo by Rubén Ortiz-Torres of a La Caracao store in Pomona, California, we see that anything in anyone’s cultural past can be turned into an attraction. Symbols and edifices that were once the center of a nation’s identity have now been commodified in a grocery store. And think of what is not in the photo—of clothing lines, music, of appropriations in our social media feeds that we don’t think about twice. As the title of the photo indicates, this is a piece of another country, but what it ultimately becomes, despite best intentions, is a spectacle, a diluted fragment of a culture meant to attract consumers and give them a “taste” of something different than what they see daily. Photographs by Connie Samara depicting trailer homes at night become representative of the immense isolation that registers throughout the collection, and if we stare long enough, it is not difficult to imagine a person sitting on the couch inside these homes, watching the news or a show until they fall asleep to the TV’s bright, American glow.

Every poem in this book invites us to pause and examine our interactions with everyday objects, events, and people, and more importantly how we see ourselves in the face of so many harmful perspectives. As the speaker reflects near the end of the book in “Vanishing”:

all persons provisional in settings that reflect, I cover ground, I quicken, I substitute the vanishing with constituent parts, regenerate, deprived of a halo, released from this fixity, am I not without radiance of my convenient forgetting and, everyday—because it so beckons—in the recurring custody of a world, around whose mindfulness we congregate, and over which we are inclined to argue?

Tejada’s speaker wants to reiterate, if not to themselves then at least to readers, that we are humans and that we deserve “radiance,” regardless of the circumstances of our being. Why the Assembly Disbanded is a powerful book that pushes poetic boundaries and encourages us to apply to our lives what we observe. For the sake of ourselves and others, let us not cease until we are changed.

II

Regardless of generation, global event, or time of year, Orwell’s 1984 is always apt for quoting, and one of the passages that most comes to mind when examining William Lessard’s instrument for distributed empathy monetization is Winston’s realization of the hold Big Brother has on everyone’s life:

Always the eyes watching you and the voice enveloping you. Asleep or awake, working or eating, indoors or out of doors, in the bath or in bed—no escape. Nothing was your own except the few cubic centimetres inside your skull.

In the world of 1984, there is no escaping the constraints placed upon every citizen, even in the comfort of our own homes. But when we think of control, we first tend to think of systems wielding their power on a mass, governmental level, and not necessarily on a level that affects us less explicitly, such as through society’s hierarchical culture or through the language of public and virtual spaces. But in Lessard’s work we see both a sort of leaked instruction manual for enacting such control and subtle, poetic ways of resisting it.

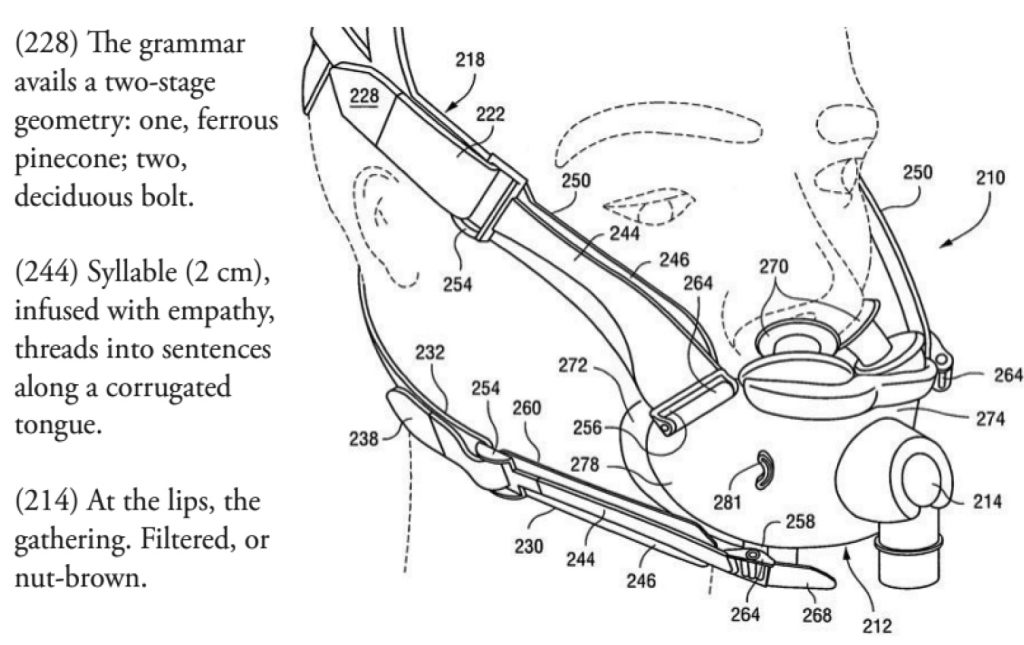

Like the cage on Winston’s head at the end of Orwell’s classic, the contraption on the head of the figure Lessard includes throughout the collection demonstrates the grip those with power, wealth, and status have on those who do not:

Reprinted with permission from Kernpunkt Press

As the poet Peter Valente indicates in the book’s foreword, “Every year, with every advance in science, the upper classes replace a part of the body. The goal is to erase the human … The populace is simply human, flesh and bone, and thus at a significant disadvantage.” The diagram looks like something one would find in furniture instructions, but unlike an IKEA bookshelf, (244) shows how the populace’s corrugated tongue—one that is inherently detrimental to those who want compliance—needs to be infused with a manufactured empathy, one that will be more favorable to the ruling class. How many times have we seen this play out in the public sphere, especially given the ways in which the pandemic has altered the American mindset about work and one’s value? Comments from certain politicians in the last year have deemed workers “lazy,” “freeloaders,” and even “unpatriotic” because they would not return to minmum-wage jobs that were still hazardous, not to mention that in most major cities, the cost of living has drastically outpaced wages. The illusion of capitalism has been shaken, and even a figure like Jeff Bezos—not the best role model for worker’s rights but someone who on the surface espoused greater worker autonomy—has dropped the façade and criticized pro-unionization efforts at Amazon and other large corporations. And yet, there are those who will lecture others about free market capitalism and trickledown economics, as though it is the end all and be all of the American way of life.

The muzzle keeps tightening, and the lips, if not contained, will no doubt lead to a “gathering,” one that is not as diluted as the voice found in “R>N:”

Here, the subject—whether that subject be a citizen or employee—has already been broken enough to believe that being under scrutiny amounts to love. Joy has become a thing that lives on the outside, that is merely a shadow of what the speaker hopes to remember, but which is slowly fading into the past. The speaker has learned to if not sympathize with those overseeing them, then at least to imagine their constraints and environment as something different from their own reality. Yes, eternity, and everything that it encompasses, is always overdressed, but it is essentially rendered as obsolete when one isn’t given the chance for it to materialize.

Both the body and mind are at risk in Lessard’s work, but that is precisely the point, to show such a risk and lay bare the intentions of the institutions and systems that claim to be on the people’s side. As indicated later:

The Company performs personhood alongside other portfolio assets, alignments, atonements. The glass cheek of the interface swells with the thrum of syntax. Heavy trading in blue-chip syllable, priced to future one.

On the one hand, it’s becoming more common for companies to promote certain social movements and issues like Pride Month, or Juneteenth. On the other, one can’t help but believe these companies are jumping on the bandwagon in order to increase their bottom line. The best advertisements, and by that extension the best propaganda, are embedded in language that doesn’t sound like it is trying to sell you anything; rather, it can be so colloquial (performing personhood) that when one finally recognizes its true intention, it is too late. Lessard is asking us to stop and consider, on all levels, the people who will ultimately fail us. When diving into Lessard’s work, one is diving into a world that no longer feels merely fictitious or conspiratorial; it feels like reality, and no matter how alluring the possibilities of “enhancing” ourselves, we must proceed into the future with as much curiosity as skepticism. No doubt we will think twice about everything when we reach the end of Lessard’s remarkable collection.

III

Huỳnh Công Út’s photo “The Terror of War” became synonymous with the horror and injustices of the Vietnam war, and although the image of Kim Phuc naked and scared might be hard to digest, it’s an honest telling of the the war’s brutality, and of how ideology can lead to such destruction and devastation. As with any major conflict, literary narratives of Vietnam are abundant and all uniquely important. Sophia Terazawa’s Winter Phoenix is an eloquent and emotionally honest collection that documents and navigates the complexities of the Vietnam war, along with the aftermath of displacement and the unspoken trauma between a mother and daughter.

Throughout the collection, exhibits, cross-examinations, bylaws, redactions, and testimonies—each poetically rendered—vie with true accounts of the harshness and brutality of the war. The book plays out as a trial with multiple speakers, the main one being the daughter. Sometimes one hears the voice of a solider attempting to come to grips with the crimes that were perpetuated. Other times one hears a forgotten voice lost to the fighting. And there are times where one encounters a combination of the two, a reimagining of a scene both horrific and illuminating, as in “Exhibit C,” which, through personal narrative, examines how violence can reduce a person to almost nothing:

The daughter-speaker poses a question to her mother at the beginning of the collection, and the question becomes embedded in subsequent poems, for every character involved in this trial asks why the others merely stood there and did nothing, why, knowing what they know now, they can only reflect on actions they could have taken to change the outcome. In the scene above, the speaker, an American soldier by all accounts, remembers seeing a woman (the daughter/speaker’s mother) escaping from the destruction he just helped to create in this village, on this hill. The speaker is searching for words to not only reimagine the scene but to add meaning to it, to believe there is something more meaningful in these actions than fear and death. But the language seeps through basic description (nouns, commas, speech, words, etc.), as though it were breaking the fourth wall of the poem itself. As Terazawa says in her preface, this collection is meant to look at the United States’ crimes against humanity in the language of American English, using the testimonies of three publicized events (The Incident on Hill 192, The Winter Soldier Investigation, and The Russell Tribunal) as source material. Terazawa demonstrates that in the end all one has is language, and if that is stripped away (from both soldier and victim), emotion, and in turn action and justice, cannot take place. Also lost is the chance to understand one’s individuality. Elsewhere in the collection, as in “N, or Variation of Haibun,” the daughter speaker asks, “what was nullified, my country or another way of speaking.” There is no clear answer, but even if there were one, a piece of her would be missing, a piece that can never be recovered.

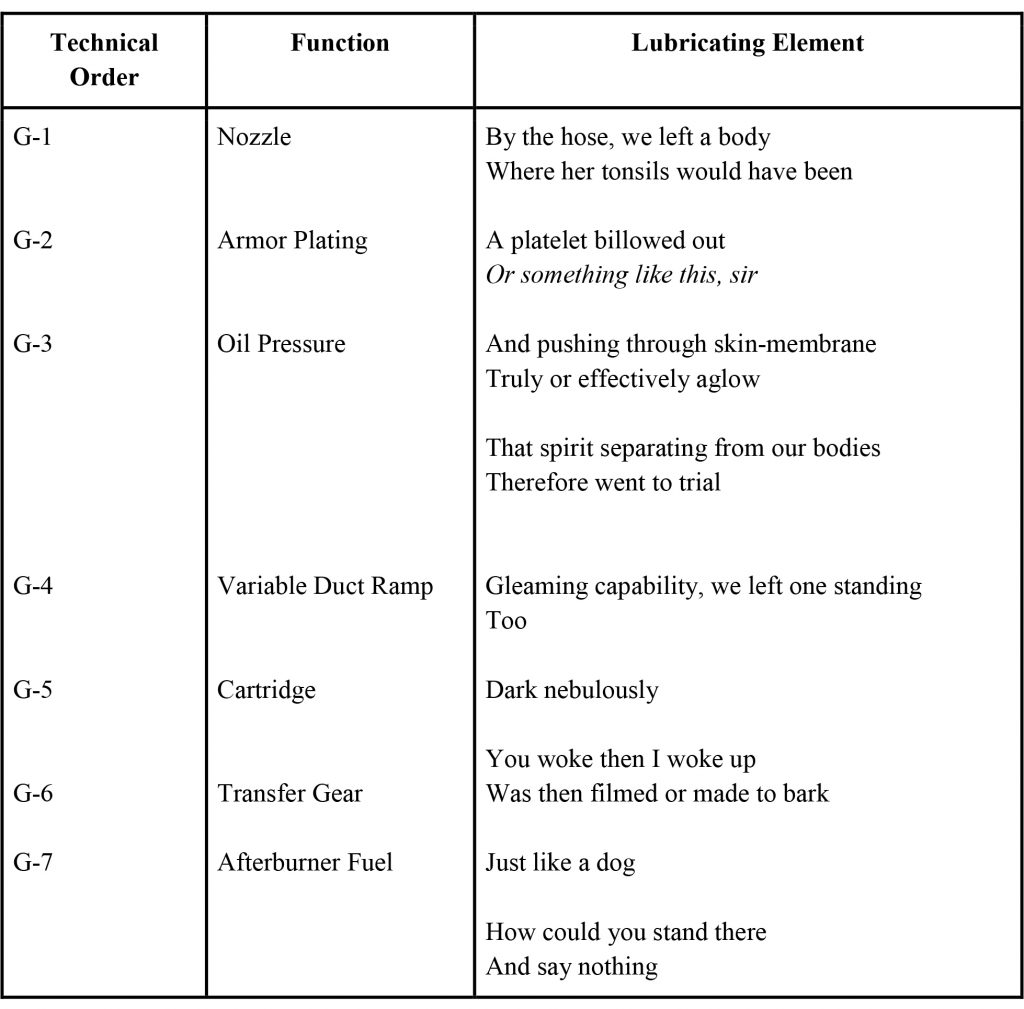

Elsewhere, we see firsthand how such “loss” was carried out, as in “Supplemental Diagrams”:

The aftermath of leaving bodies mangled, of wiping out entire families, of perpetuating death repeatedly without the slightest hesitation, isn’t a consequence of just one person, but of personnel, as shown in the Technical Order column (G-1 through G-7 being staff officers, from logistics to operations and training to intelligence). Regardless of how seemingly innocuous a function may be (such as transfer gear or afterburner fuel or viable duct ramp), its intention is to eliminate targets and people. Behind every death in war, there is a graph showing how it was carried out.

Although multiple voices jostle for attention in the collection, at its core the book centers on the daughter/speaker and her difficulty reflecting on her mother’s past. As shown in “Exhibit E,” the speaker wants to know how her mother was able not only to escape, but to forge a new path in life after:

How many of us as adults have discovered something about our parents that we didn’t know as children, then wanted nothing more than to dig further into everything about it—context, feelings, the aftermath? The speaker is not asking her question in an accusatory manner, but in a way that is curious and heartfelt. To know that a loved one has undergone such a horrific and unjust experience can be shocking to say the least, releasing an array of unexpected emotions. What hasn’t been said is oftentimes more important than what has, and there is no guarantee that even if discovered, the details and emotional weight of such an experience could ever be fully retold.

With each new conflict, the conflicts and histories of the past seem to be forgotten, mentioned only to say that events seem to be “repeating themselves.” Through a combination of surreal imagery, honesty, and questions meant to unearth answers that can often be difficult to process, Terazawa gives voice to a dark chapter of world history that should never remain silent. Winter Phoenix implores us to no longer remain bystanders.

Esteban Rodríguez is the author of six poetry collections, most recently Ordinary Bodies (word west press 2022), and the essay collection Before the Earth Devours Us (Split/Lip Press 2021). He is an editor for EcoTheo Review, Tupelo Quarterly, and AGNI.