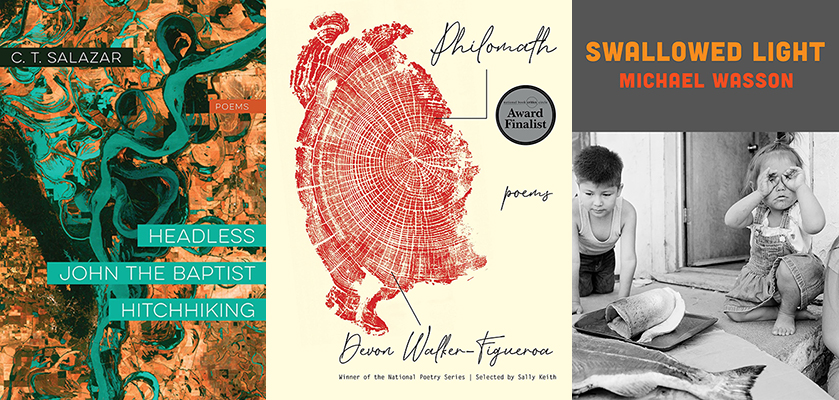

Swallowed Light, by Michael Wasson. Copper Canyon Press, 96 pp., $17.

Philomath, by Devin Walker-Figueroa. Milkweed Editions, 104 pp., $16.

Headless John the Baptist Hitchhiking, by C.T. Salazar. Acre Books, 78 pp., $16.

Perhaps it is not a surprise that I’m drawn to mythmaking in poetry. After all, many of my own first memories are of stories, folklore, and myths being recited. In their debut collections, Devon Walker-Figueroa, Michael Wasson, and C.T. Salazar make mythic the rural landscapes that shaped them, through incisive portraits, lyrical transformations, and preservation of disappearing language. But even as poets engage in mythmaking, they often reach for what is familiar. Engagement with source texts—whether folklore, European mythology, or the Bible—invigorates writing in unexpected ways. I often wonder what makes us writers reach back toward God and religion. What makes us hold on to the storytelling of elders and ancestors? Why do we write about home even in new places—when we can create any world we want through language? Since I turn to such source texts myself as a poet, I have answers of my own, and I can’t help but admire how these forces manifest in the work of fellow poets.

I

Tinged with mourning, Michael Wasson’s Swallowed Light deals in folklore, history, and the preservation of a vanishing language. These poems are riddled with ghosts and bones, bullets and colonization, and the space between the dead and the living. They are also woven with nimiipuu stories like that of the Ant and the Yellowjacket as well as Biblical references. As I read Swallowed Light, I was reminded of Marie Howe’s famous last line, “I am living. I remember you.”

As with any good first poem, “Aposiopesis [or, the Field between the Living & the Dead],” is a guide to reading Wasson’s book. Fragmentation of language or thought, or aposiopesis—the rhetorical term for an idea broken off or a speaker trailing off mid-sentence, unable to continue—is what exemplifies this debut. There is an omnipresent tension between what is and what could be if the dead were still alive. Wasson writes in this opening poem,

The short lines with monosyllabic words feel light but then transform into heavier, polysyllabic lines as if weighed by grief. Wasson often splits words in two on the line break or across caesurae or blank spaces, such as “blood- /warmed,”, fracturing language works to convey duplicity or deliver surprise. For example, in “Ezekiel 37:3”:

Here we see an internal break created by a slash which causes an additional pause on the line’s thought or creates an intentional disruption that splits a single thought into two, adding texture and multiplicity to the poem. The breaking of “hummingbird” into two words so the line at first reads “in translation. Where my heart is / the very same humming-” invokes sound and when read together with the next line shifts the image entirely to encompass both the sound and image of a hummingbird. This happens again in several other poems. For Wasson, fracturing does not always result in permanent breakage but teaches us that breaking when done skillfully results in richness like kintsugi, the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery with precious metals like gold to celebrate and highlight an object’s history.

One of the most admirable moves in Swallowed Light is “paq’qatát cilakátki” a poem written entirely in Nimipuutímt, the Nez Perce language. Originally “paq’qatát cilakátki” and the poem that follows, “Close to Each Other With [a/the] Body,” were published together for a 2016 translation feature by Broadsided Press. In an interview with the press about the poems and how translation fits into his work, Wasson said:

A hand. Or a shoulder. A jawbone. I never asked how my arm fits to my body. It’s just my arm. But many of our ‘creative’ lives somehow involve language being a conversation between the unsayable and the transformative. I like opening possibilities. So when nimipuutímt blossoms a smidge out from the page, I let it be. Just let it ache and breathe and be alive there in its beautiful little textual and/or sonic breach.

Translating “paq’qatát cilakátki” is not as easy as putting the words into Google translate. As with many Indigenous/First Languages, the reader must seek out tribal resources like the Nez Perce Language Program. Although translating requires much time and investment, there is a deep enjoyment gained by simply attempting to sound out the words or viewing them on the page. It is important to recognize that a disappearing language is not just a loss of words but of culture and myths. It is a reminder that colonization is deeply insidious, inflicting violence that makes language inaccessible, thus erasing groups of people. Miraculously, and in spite of this, the language continues to survive. “paq’qatát cilakátki” holds space for nimipuutímt and the nimiipuu people. While a book is crafted for a broad audience, the entirety of its language needn’t belong or cater to everyone. In a publishing industry that continues to prioritize the white gaze and uphold the values of colonization to make writing palatable, resisting legibility like this is worthy of celebration. I can think of a handful of recent American poetry books that include poems entirely in a non-English language, but I particularly admire it here as an act of preservation.

Although fragmentation and aposiopesis characterize Swallowed Light, “World Made Visible” brings clarity to the specters of loss shrouding the book. In this two-page poem that fills the page from margin to margin, a best friend’s suicide and a father’s imprisonment are revealed. The poem begins:

& this is where you stand with a gun the size of American centuries that has already entered your boyish body but in this version of the lullaby the gun isn’t loaded with bullets but the teeth of those who sang you your first name it sounded like bones rattling against one another in the back of your throat until you could finally say xayxáyx

The language of the poem extends and moves in a single sentence strung together with ampersands as propulsion points. Imagery related to guns, teeth, and bullets appear often in Swallowed Light. Wasson describes bullets in relation to teeth, for instance, “the gun isn’t / loaded with bullets but the teeth of those who sang you your first name” or “a gun there & a tooth-sized bullet”. Bullets and teeth almost become interchangeable as a result. The differing amounts of danger that teeth and bullets pose is vast. What does it mean for a gun to be filled with teeth rather than bullets? Particularly where they’re the teeth of “those who sang you your first name”?

In a previous poem called “Self-Portrait toward a Fugue [No. — in —♭Minor],” he writes, “I say I will change the world / in my wildest dreams—which means the bullets loaded / in my mouth are only teeth: & only crooked teeth.” In this instance, there’s a de-escalation where it’s clear that the speaker believes to “change the world” they must depart from bullets and return to their humanity—back to their body.

Swallowed Light’s idiosyncratic language creates tautness and a visceral feeling of ache. The speaker’s many-faced grief is felt well after closing the book. Though Wasson’s poems aren’t always elegies, the speaker’s recognition that the dead are still present is essential. Stunningly lyrical, these poems ring like a death knell.

II

A born storyteller, Devon Walker-Figueroa crafts a memorable place in literature for the town of Philomath, Oregon. We see surrounding areas like the ghost town of Kings Valley (where the poet grew up), the Chemeketa Community College, and Cape Perpetua. In these skillfully crafted poems, her compelling details and attentive characterizations make small town squabbles and drama feel almost larger than life. We’re invited to see and know Philomath through the eyes of a local in the titular first poem, in which we are told:

These lines welcome us into town and give us insider information. We see what the kids of Philomath do for fun, which is the same as what kids do in any small town. More interesting is the suggestion of departure in the line break “looking for places to leave.” And how wonderfully telling the list of items that follows, like new tire chains, Lucky Strikes, feed, and pocket knives. We learn what’s important by being told where to pick up these items. We know this is a farming town, where folks smoke and need chains for winter.

In this surreal scene, we learn about the town’s relationship to religion:

There’s such a profound strangeness in the seemingly impossible task of sucking pudding through pantyhose, but as the poet writes it’s “to show how far we’ll go / to be forgiven.” The desperation to be saved whether through religion or getting out of town implied by the strategic line break in the previous passage resonates throughout the poem. The speaker later reveals and further reinforces these ideas when she writes about school:

Every line break here is building towards the speaker’s ambivalence, at once showing disdain for the kids who will leave town for college because of 4-H, and the feeling of despair that “the teachers have given up” on “… everyone. I care about.” It is such a perfect depiction of adolescence—trying to be above caring but caring deeply anyways. Line breaks like “I feel alone …” and “They belong …” embody adolescent feelings of outsiderhood, , the flitting changes of heart.

I am also struck by the unwavering attention the poet gives other people in the book. There’s Megan who drinks cough syrup and gets hit by her father after being saved; war veteran Mark who wants to be called Lucky and as the speaker says, “takes it upon himself to learn me / vigilance;” and the speaker’s friend with dying tooth who says:

At times a dark humor comes through in these poems, as in Susan’s joke in “Beginning Wax to Bronze Chemeketa Community College,” a poem in which the speaker is working to cast a pig’s heart “the closest thing to human” in bronze. Philomath reminds me of Southern Gothic literature. Religion is puritanical and the imagery is grotesque and uncanny.

Walker-Figueroa is extraordinarily adept at long poems (three or more pages), such as “Persistence of Vision.” Named for the optical illusion that results when an image lingers after being removed from vision—for example, the trail of light from a sparkler at night, or the fused images of a thaumatrope (which the poet describes in the poem’s second section)—the poem moves from scene to scene in eight sections that work like after-images. Each distinct section resonates back to one that came before, beckoning us to ask, how does this section relate to the last? As soon as we’ve asked the question we come to understand that the main speaker is contemplating the loss of her mother.

The poem includes sections written in personas like the martyr Perpetua’s prison guard and a girl’s dormitory on fire. In the latter, she writes: “the girls / pound their fists on my locked / windows, raising what voices are left / them.” An echo of these lines comes in a later section, where we learn more about what has happened to the main speaker’s mother. Walker-Figueroa writes,

In another harrowing fire, the image of raised fists and the voice are brought back again. In this carefully woven poem, I want to note something clever Walker-Figueroa does to link the main speaker’s sections. She doesn’t end these sections with a period or another final punctuation mark until the final section, seeming to suggest a continuity and maybe even the idea of reading them together. Such extra attention to craft is what makes her long poems so effective.

Philomath is an astonishing debut. After reading this book and learning that Figueroa-Walker is working on an MFA in Fiction at New York University, I am now anxiously awaiting her prose.

III

Sonically decadent diction and striking imagery exemplify C.T. Salazar’s debut, Headless John the Baptist Hitchhiking. In poems entrenched in religious and bucolic imagery, Salazar imagines a landscape that is both beautiful and mired in violence. As the poet writes, “Mississippi / burns you last if it loves you.” Salazar, a resident of Mississippi, gives us a book of biblical characters, country, and the struggle to define faith.

Admittedly, I found myself seeking out the book’s sonnets because of my deep admiration for Salazar’s chapbook American Cavewall Sonnets (Bull City Press, 2021). Sonnets appear twice in the collection, including a sonnet sequence called, “Sonnet River,” which also appears in the chapbook. “Sonnet River” is composed of five interlocking sonnets that are structured in two stanzas—an octave followed by a sestet. Every line has ten syllables, which surprisingly doesn’t cause the poem to sound monotonous. It does, however, cause some clunky line breaks.

Like many poems in the book, the “you” and “I” seem to be ever-changing in this poem. The “you” at the beginning of “Sonnet River” seems to be a general “you,” but as the poem unwinds the “you” becomes more intimate, like a beloved. The speaker calls the “you” things like “tricycle child,” “Baby,” and “Love.” At times it’s difficult to keep track of this speaker as they seem to be roving and disembodied, but Salazar has a way of working towards tenderness. By the end of the poem we’re situated again—or perhaps simply made more comfortable in a softer linguistic landscape, in awe of its vividness.

Salazar is meticulous in his construction of poems and especially in his sonnets. In the first sonnet of “Sonnet River,” Salazar writes:

In the first passage, the colon seems to suggest a relationship between King James and Remington which is restated as “lightning bolt.” Lightning in the Bible is traditionally a symbol of God’s wrath. The imagery here reminds me of Psalm 78:48-49: “He also gave up their cattle to the hail, And their flocks to fiery lightning. He cast on them the fierceness of His anger, wrath, indignation, and trouble, by sending angels of destruction among them.” In the second sonnet, the poet goes on to describe a landscape where “God’s gospel / gets lost before it gets here, and hardens / from a river into a rattlesnake” then the speaker says they, “press every cow skull to my chest.” Of course, in the King James Bible there are many passages where lightning is mentioned. Psalm 78 aligns with the poem’s imagery of dead cattle, lightning, and destruction under God’s wrath. Moreover, in the context of Salazar’s poem “sending angels of destruction among them” could be interpreted as guns.

In the second sonnet, the punctuation does a lot of work to reinforce these ideas as well. “Lightning bolt” is now split by a comma so the word bolt becomes “bolt action,” which is another type of gun. The poet goes on, “all of these can fill the body / with a new knowledge.” Like Wasson, Salazar appropriately identifies guns as a source of American violence, reminding us that the United States eclipses other countries in the number of cases of gun violence and school shootings.

Although “Sonnet River” is filled with danger, weapons, and violence the poem reaches towards gratitude and hope in its closing lines: “If the season / whittles us down, hallelujah our spines. / Praise out hollow-bell bodies still ringing.” We also return to the “ringing” which was established earlier in the sonnet sequence under the conditional “if the ringing reaches / God.” So often Salazar juxtaposes what is beautiful and holy with what is destructive, which feels natural since the Bible describes God as both.

Though this book brims with references to religion, in many of Salazar’s poems the relationship with faith is complicated. An example of this is in “Mostly I’d Like to be a Spider Web,”

The speakers of Salazar’s poems often praise and worship small things, as if they’re trying to define faith on their own terms while wrestling with organized religion and the concept of God. Salazar uses both the big G god and little g god in various poems throughout the book; the use of little g god here appears to reinforce the speaker’s doubt. The final stanza discloses the speaker’s worry that they might not be accepted as they are—spiders and all.

Salazar doesn’t offer exact answers while examining faith, but in “Love, Circular Saw Blade” he attempts to measure it. He writes: “In the field the last cricket of summer / declared itself the size of my faith.” That the cricket says the speaker’s faith is the same size as itself presents a thought-provoking complexity. Size is relative to what it’s compared to and the cricket has compared faith to itself. Does this mean the size the cricket describes is larger than what the speaker (who is presumably human) thinks? I would say something is big if it’s my size or larger. Conversely, faith would be much smaller when comparing a cricket and a human. The inexactness of this measurement wonderfully evades a definitive answer.

Unlike Walker-Figueroa, who portrays the town of Philomath using mostly realism, the strength of Salazar’s world based on the South is less grounded; his descriptions reside in emotional spaces and at times are surreal. Feelings of unbelonging and struggle appear when he examines the subject of America. Perhaps we writers reimagine and shape new worlds when the one we reside in doesn’t feel like our own. Salazar asks us to “imagine a country / where you and I kiss before we burn / our battle flags” in his poem “As Long as You Want.” But this isn’t the only place where the country is linked to battle. In “Poem with the Head of Homer in It” he writes,

We see uncertainty in “this may or may not be my country,” followed by the certainty that both the speaker and the American Dream “will be dead in no time”. The choice of centering Homer’s marble bust in the poem is significant since Homer wrote of war, family, and the journey home. The speaker transmutes into stone as if becoming the bust after telling himself, “there’s more than one kind of battle.” Salazar does not reveal what those other battles are, though we can infer that they’re linked to America because he later says “my country / cracking me.” If the speaker didn’t turn to stone would he resist cracking? How do we prevent hardening or becoming unrecognizable in a country like this? In Salazar’s world, even the cemetery changes into a field over time.

As poetry books seem to get longer and longer, approaching or exceeding 100 pages, I appreciate that Salazar’s is a mere 78 pages, closer to the page count of poetry books from past eras. Although length is often a result of contest and publication guidelines and expands after typesetting, I wonder if such guidelines encourage adding poems that would better serve another project. By comparison, Headless John the Baptist Hitchhiking is cohesive and the thematic threads never feel overstated. While this book is smaller than many of its contemporaries, the multitudes every poem contains are immense.

Laura Villareal is the author of Girl’s Guide to Leaving (University of Wisconsin Press, 2022). Her writing has appeared in Guernica, The American Poetry Review, AGNI, and elsewhere.