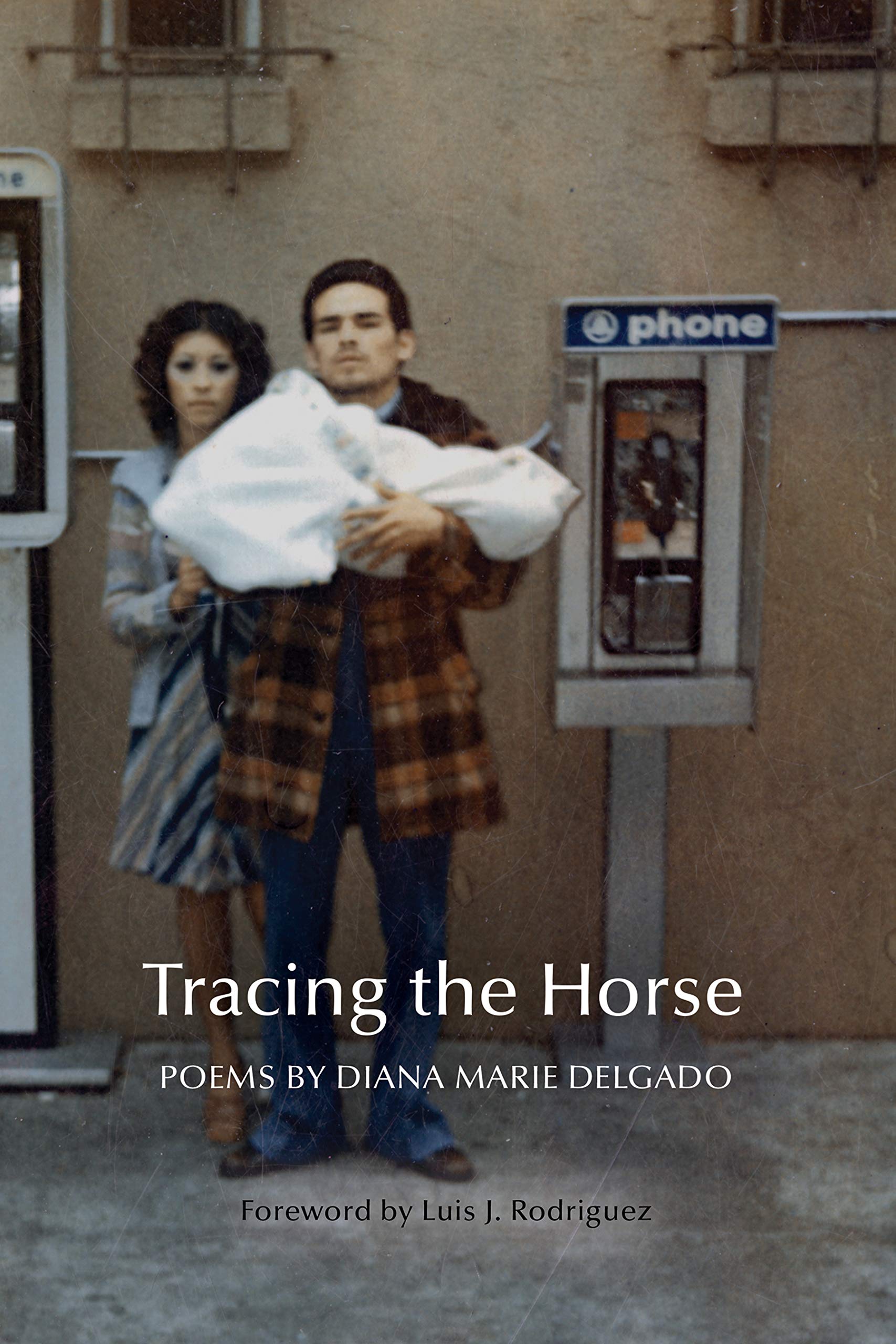

Tracing the Horse, by Diana Marie Delgado. BOA Editions 112 pp., $17.00.

“Most nights I’m face to face with the stars. / No one is more afraid of this than me. // So I find places to lie down/and signify,” Diana Delgado begins in “Little Swan,” the first poem of her debut poetry collection Tracing the Horse. “Little Swan” sets the tone for the collection, which has a dreamy, interior quality that is by turns punctured and influenced by the chaotic elements of the speaker’s life, as the next lines are:

The voice of these poems drifts over their images, pivoting between them and positioning the speaker as slightly removed from them, even as she engages in vivid description. The speaker is sometimes nostalgic, sometimes cynical about those images, which follow close on each other, as if disconnected.

The way Delgado shifts and shifts and shifts between these subjects allows their emotional resonance to arise out of the poem. We discover, slowly, by a process of accrual, their emotional weight. By the end of “Little Swan,” the adult speaker connects her nostalgia for infancy to a wish for death; if only she were an infant, then she could be the child who needs to die in this story. If she can’t return to a state of pre-life, a fetus in her mother’s belly, maybe she can hold herself aloof from the world, as she is held aloof from these poems, by dying. We can’t help but connect this wish for distance, for beforeness or afterness, to the poet’s pose that appears in the beginning of the poem:

I am separate from the world, or wish to be, the speaker seems to say, but this is what allows me to make meaning—and to be meaningful. The speaker wishes for a selfhood held apart from a world that can seem overwhelmingly large and insignificant or unfair. Her ideal self sees, understands, signifies, but stays separate, on a slightly different plane like a fetus or a corpse must be.

Many of the poems in Tracing the Horse indicate that this wish for separation and a return to the innocence of infancy might be connected to traumas their speaker has suffered, as the next poem in the collection, “They Chopped Down the Tree I Used to Lie Under and Count Stars With,” does. The title of the poem unravels the childlike wonder that propels the first poem in the book. Someone has disrupted the speaker’s ability to “to lie down/and signify” by chopping down the tree she used to come “face to face with the stars” beneath. “I tape a red telephone to its ear so the fetus appears to speak to someone,” the poem begins,

One of the most impressive qualities of this collection is the way Delgado trusts the reader enough to allow her seemingly disconnected images to accrue. The effect is that from line to line—and from poem to poem—our sense of the speaker and her story becomes more and more clear, as it does here, without Delgado having to explicitly direct us. We can understand this as a reflection of how one might process traumatic events—slowly and indirectly, so that they are tolerable. We can’t be sure whether the pregnancy that appears in these lines is the direct result of a sexual assault, but we certainly feel the ways that these traumas are connected in the speaker’s mind and, in the next lines, the ways that they contribute to her wish for a return to an untraumatized state of infancy: “Look into the picture, see yourself before any of this happened./I dream, I tell Marcos, of combat; I reach down and weapons appear.” The contrast between these two lines is stark—we see the speaker as the baby in her own ultrasound—“before any of this happened” she was as innocent and inert as a fetus. Now, she is prepared for battle, even in her sleep. “When you see yourself is there an observer?” she asks later. She observes that old self, the fetus self, from the vantage of someone who has been traumatized. Trauma, having a seepy quality, leaks out into many aspects of the speaker’s life and perspective, including the ways she observes this past self.

The speaker’s pain, here, leaks into everything: into family culture, into the media, into the intimacy of the home. The death wish returns: “I’m kissing a boy in his car, below a streetlamp vibrating with moths. / I pretend to lie in sand, be part ocean, dust from a candy cigarette … / Grandpa, putting money in my hands: Ride that bike like the wind.” It becomes clear that the painful events and menacing impressions that occur throughout aren’t one-offs. They are a pattern of sometimes gendered or racialized violence, which occurs even in the places the speaker should be able to feel safest. She reports, “A boyfriend: You blacked out. We had sex to calm you down. / Your pussy’s like a clamshell, it closes like a purse.” She too, closes, here, as she indicates she will in the earlier lines, “One day you’ll think of men—and it will be like looking at a gray wall.” The only response the speaker can muster is to ride “through stars, through streets where the wind talked to us,” as her grandfather tells her to, escaping into a kind of childhood. Even then, “savage birds called out; I looked up and listened.”

The wish to escape is the wish to be left alone with the real, secret self, the self of the childhood and, maybe, the self after we’ve died, the self who disappears as we are “face to face with the stars.” The speaker’s feelings about her childhood, though, are ambiguous. The protection of the parent-figures in these poems seems uneven—sometimes good, sometimes inadequate—as if, maybe, there was more they could have done to prevent the trauma the speaker underwent. In “Free Cheese and Butter,” for instance, the mother is “good at waiting. / We can stand for hours,” she says, but the speaker and her brother seem shielded from the discomfort and/or necessity of the wait:

However, in the next poem, “Twelve Trees,” parental protection is portrayed as mixed at best. The speaker’s father does yard work:

In a matter of lines, the father and the Devil are conflated—which of them is raking leaves and which fixing umbrellas? Who does “he” refer to? A handsome, charming devil or a sometimes-devilish father? Delgado is able to create a complex portrait of the father figure by leaving it ambiguous. He is simultaneously devilish, handsome, and smiling in all his pictures, and wholesome and spontaneous as he rakes leaves and sings. “Late-Night Talks with Men I Think I Trust” deepens this impression. “He’s made me smaller,” the speaker begins without identifying who the “he” is—but the poem’s images are mostly rooted in family life:

We imagine a childhood for the speaker that is, in some ways, repressive, in which she and her siblings were scared to talk over the television. “Through cattails, children led horses. / Dogs gnawed on shards of bone,” the speaker goes on. She’s able simultaneously to develop a sense of a child-world, entirely separate from that perhaps-repressive home-life, and a sense of meagerness, of unsafety. “We belong to these conversations,” the last lines of the poem say. “That’s why it’s taken me this long to write his name. // I did what no one’s ever done: / I met my father.” We can’t be sure, here, whether the name it’s taken so long for the speaker to write is her father’s or the name of some other man who’s “made [her] smaller,” but no matter who it is, the speaker’s father seems complicit in keeping the poem’s speaker from giving voice to her experiences. In these last lines, the father becomes an idea that is inaccessible and imposing, so removed that just meeting him feels impossible: “I did what no one’s ever done …” Again, Delgado’s quick-changes between different subjects and images allow these moments to do double-duty. The father feels both like a real father who was absent and over-hard on the speaker—and like an archetypal patriarch, a stand-in for the type of masculinity that makes her feel small.

These ambiguous feelings toward the speaker’s parents are repeated throughout Tracing the Horse with varying levels of explicitness. In “Vecino Drive,” the speaker presents a succinct excerpt of the abuse that she suffered or witnessed: “Once Mom got the nerve to scream, ‘Stop hitting her’/from the top of the steps, only for Dad to get out of / bed, yank her in: It’s none of your business.” The penultimate poem in the collection, “Nevermind I’m Dead,” calls back to the feeling of collection’s first:

We return to a kind of nostalgia—the flawed, complicated kind that pervades this collection. We can go back in time, the first lines assert, but only to ruins. We can’t quite return to the person who is “face to face with the stars” most nights—here, they’re nearly falling out of the sky. At least, though, there might be a return to a childhood that allows the speaker the sort of imaginative escape (“I find places to lie down / and signify”) she got the first time around, the sort of imaginative escape that this collection embodies at every turn. There might be, even, some of the protection she’s wished for, even if imperfect:

This isn’t redemption, which is proven by the last poem, “La Puente,” which catalogues experiences in which the speaker’s family rubs up against prison or crime—but there is relief here and in the last lines of this last poem. In the end, that relief is seated in the speaker, in her ability to imagine, to signify: “I lived next to a train crossing on Valley Blvd, the sky above pink-and-gold stars. // Summers were horses traced on denim; my youth unfolding, paper fan.”

Katie Berta lives in Phoenix, Arizona where she works as the Supervising Editor of Hayden’s Ferry Review. You can find her book reviews on the Ploughshares blog and forthcoming in Harvard Review and The Puritan. Her poems appear widely in journals.