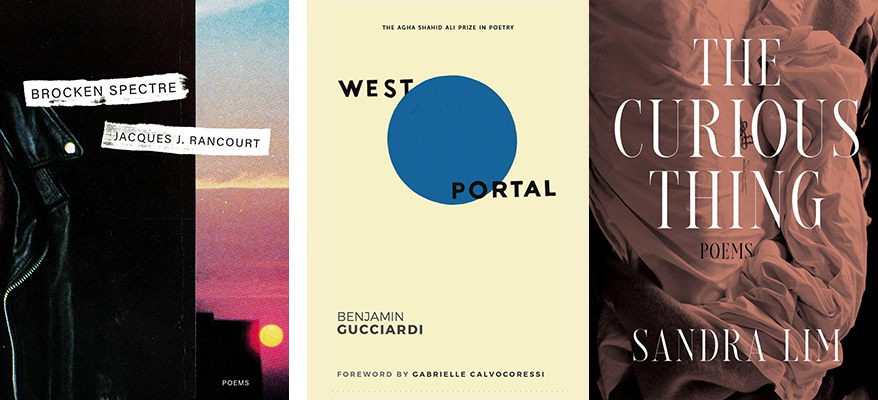

Brocken Spectre, by Jacques Rancourt. Alice James Books, 100 pp., $18.95.

West Portal, by Benjamin Gucciardi. Unviersity of Utah Press, 64 pp., $14.95.

The Curious Thing, by Sandra Lim. W.W. Norton & Co., 72 pp., $26.95.

Split the Lark: Shara Lessley on Contemporary Poetry

With the proper elements and elevation, a shadow projected onto fog can manifest a mirrored self: an eerie, three-dimensional figure borne of sun and mist. Christened brocken spectre in 1780 by a German pastor with ambitions in geology and hydraulic engineering, the optical effect is meteorological. Water droplets and light intersect to give the impression of a dim figure, often haloed, who seems to approach from a distance. Sometimes, the ghostly shape is magnified to a disturbing scale; sometimes, the mirage stays still. Regardless, the outline of self is both peculiar and familiar, supernatural and scientific; its meaning left to the mercy of one’s own imagination. Place-dependent, brocken spectres are encountered not only near cloud banks, over high peaks, across rolling dales and fog-locked moors, but also in literature: “He finds on misty mountain-ground / His own vast shadow glory-crown’d,” writes Tennyson in In Memoriam A. H. H., “He sees himself in all he sees.”

For this installment of “Split the Lark,” I initially intended to highlight collections that respond to and investigate the private experiences and particularities of place. It’s true that Jacques Rancourt, Benjamin Gucciardi, and Sandra Lim render the bars and parks of San Francisco, Chicago’s trains and crowds, the Holy Land’s ancient gates. The poems likewise recount pleasures and sorrows experienced on the Pacific and Atlantic coasts, and narrate histories that play out in countries including Italy, Portugal, Greece, and Korea. But more than surface encounters with cities or rural locales, what Brocken Spectre, West Portal, and The Curious Thing share is a deeper consideration of the tensions that arise from the collision of self with grief. As in the case of the above excerpt from Tennyson’s great requiem, Rancourt, Gucciardi, and Lim are haunted by questions of perspective, self-projection, and the nature of imagination when met by loss.

Like those hikers or ramblers who witness the luminous brocken spectre, readers sense in each of the collections under review a counter-presence, an apparition of sorts that unsettles the poet and drives thought forward. Born at the height of the AIDS crisis, Rancourt wrestles with the fact “that six hundred thirty-six. / thousand of us died & I did not. / know a single one.” (“The Wake”). Gucciardi grapples with the aftermath of his sister’s fatality due to addiction and diabetes, the pain his art students face at school and at home, and the quiet realization that “I’m kinder to the dead than I am to the living” (“Rendering the Pose”). Lim is haunted by the disappointments of eros, the inevitable pain of attachment and detachment. Like the beloved deceased in Tennyson’s elegy who“sees himself in all he sees,” each of these poets perceives, from a distance in place or time, some counter version of self—an experience that alters, disorients, but ultimately synthesizes the past and present, drawing insight into sharp relief.

I

“The existential threat of AIDS drove many queer people inward, forcing them to confront their own mortality, the strain of caring for sick lovers and friends, and the persistence of shame in the wake of ostensible liberation,” observes critic Sam Huber in a recent essay for Yale Review. We see these tensions play out in verse first published in the early 1990s by Thom Gunn (The Man With Night Sweats) and Mark Doty (My Alexandria) and, more recently, in the memorializing work of Mark Bibbins (13th Balloon) and poetic memoir by Pamela Sneed (Funeral Diva). Unlike the above poets, however, who chronicle the epidemic from the vantage of witness-survivor, in Brocken Spectre Jacque Rancourt speaks from the periphery, quietly taking into account the elision of time and cultural memory decades past the outbreak’s height.

The poet’s sophomore collection opens with “Near the Sheep Gate,” whose title casts its stanzas, as well as Brocken Spectre’s entirety, with an invisible backdrop borrowed from a scene in the New Testament during which the sick and marginalized visit a bathhouse in hopes that its waters will ease or cure their afflictions. Rather than restaging the miraculous healing as depicted in the Gospel of John, however, Rancourt’s newly married speaker acknowledges to his husband that “Had we been // born twenty-years / back, we might / be counted among // the dead …” The dead, of course, are those lost to HIV/AIDS following the virus’s “official” onset in 1981—forty years before Brocken Spectre’s publication. Yet, despite its remoteness in time, the book insists that everything is connected. Take, for instance, how the understated diction in “Near the Sheep Gate” reveals a rich dimensionality. Set in stacked tercets, the poem is part nature poem, part epithalamium. An elegy for the queer departed, its Biblical allusions and interiority are also in dialogue with the devotional lyric. “Near the Sheep Gate” is humble. And erotic. It counts its blessings: “we live,” concedes its speaker in the third stanza, “in the easier century.”

If increased visibility and advances in medical research make the current century somewhat “easier,” Brocken Spectre suggests that the lived experience of our current moment is by no means less complex. A quick scan of the table of contents reveals the collection’s pull between faith’s residue, as demonstrated by titles like “Jacques, from Jacob, Renamed Israel, Which Means, in Hebrew, He Who Wrestles God,” “Heaven’s Kingdom,” and “Golgotha” versus the existential realism of entries like “The Earth Is Rude, Silent, Incomprehensible,” “Where to Begin?,” and “The Loons Prove That Even before There Was a Word for Grief It Existed as Song.” The interiors of the poems themselves are likewise multilayered, and often exhibit a range of competing feelings and impulses within their individual stanzas and lines. Whether the setting is rural or cosmopolitan, rooted in recent events or time-stamped in the past, everywhere, it seems, lurks the possibility of death or reminders of its impact: a first date ends in cardiac arrest, “Termites eat out the tree’s / giant heart,” gay bars and sex shops are shuttered, mountains catch fire, a beloved pet perishes, factories are abandoned, a mass shooter terrorizes a dance club, Hale-Bopp “blip[s] over the funeral parlor // the night” a family buries a cousin lost to suicide. Yet, despite the historical and ongoing losses, Brocken Spectre renders, too, ordinary moments of quiet beauty, intimacy, and humanity: two friends skinny-dip beneath a harvest moon; people watch snow fall “in a place // we were told / would never snow” (“Wild Through the Sea”); a group of men who survived the height of the AIDS crisis congregate at a bathhouse “like a council of stars / lit blue from underneath. They laugh / silently & touch each other, / or float on their backs, staring up / at the show of light on the ceiling” (“Voyeur”).

That a number of the book’s most tender moments are associated with water—the above examples take place at a pond, coastal shoreline, and bathhouse, respectively—should come as no surprise if we remember that Brocken Spectre opens with the allusion to the public pool in “Near the Sheep Gate.” Further into the collection, however, readers begin to recognize such spaces not only for their association with religious ritual and healing, but also as communal destinations for leisure and pleasure. For Rancourt, they also become pilgrimage sites offering an opportunity for self-interrogation and introspection: “A nondescript building with a nondescript name— //,” reflects the poet in San Francisco, “who would I have been back then?” Though it’s impossible to know how the speaker would have navigated imagined rooms where “the jizz drifting like smoke // through the Jacuzzi is holy” (“At the Place of Bathhouses”), we do see him elsewhere in Brocken Spectre at a series of gardens that subtly evoke and entwine Biblical Eden, eternal paradise, modern graveyards, city and National Parks, and gay cruising sites. The speaker in “Golden Gate Park,” for example, describes walking the AIDS memorial at night while thinking about “the man who hydrated // his partner by feeding / him ice chips with his mouth.” Such elegiac musings are disrupted when “Someone stumbles // down the path, maybe drunk, / maybe a little / fucked up …” and solicits the speaker for sex. Any potential erotic encounter is delayed, however, by the speaker’s haunting recollection of a queer man who’s lured from a rural bar near his hometown on the East Coast and “beaten with a cast-iron pan, / laid across the tracks, // & severed by a train.” The rendering of this hate crime is immediately followed by a kiss from the stranger at the AIDS memorial—though the moment is once again thwarted as the speaker flashes on God’s post-flood vow that “Never again / will I destroy the earth …” From a structural perspective, it’s a brilliant shift as Rancourt undercuts and inverts God’s promise by reframing it as a question. [W]ill I destroy the earth?, the Creator seems to ask thanks to Rancourt’s use of enjambment and a deftly positioned stanza break.

Of course, the emblem of the covenant God makes with Noah in Genesis is the rainbow—a symbol that’s equally well-recognized as a marker of LGTBQ+ pride and one that hangs quietly over “Golden Gate Park” as the poem turns from the aftermath of both AIDS and the Biblical flood towards what is perhaps its final and most intimate exchange. “Once, I believed in God,” the speaker confides,

Readers now see that the memorial grove that opens “Golden Gate Park” has been replaced with a forest from the speaker’s childhood; that we’ve been transported from a public sanctuary, a site designated for communal mourning and healing, to an isolated wooded area remembered as a place of private dialogue, self-discovery, and, eventually, the repudiation of belief. While there’s violence and loss in “Golden Gate Park,” there’s also intimacy: the physical proximity required for both kissing and homicide, the closeness necessary for the exchange of promises, prayer, and parting. In the tradition of Donne’s erotically driven “Holy Sonnets,” Rancourt’s final lines rely on paradox; in this case, the idea that in recognizing his own limitations, smallness, and mortality, the speaker is somehow expanded, emboldened, and made greater. The word “enlarged” in the final line is also sexually suggestive, as “Golden Gate Park” chronicles the erotic “sweet[ness]” of the pleasure gardens “of our fathers’ generation // who’d rendezvous in parks / past dark.”

Although Rancourt’s titular brocken spectre doesn’t arrive until the collection’s final poem, “Love in the Time of PrEP,” readers sense what the speaker experiences as “some paranormal visitor, some queer saint” throughout the collection. Bored with the same cocktails and tired scenery “In the Castro,” bar-hoppers find themselves haunted by visions of the neighborhood’s decades-distant candlelight vigils during which thousands of people impacted by AIDS marched down Market Street in an act of solidarity. “Kirby” revisits a black-and-white photograph taken by Therese Frare that appeared in a 1990 issue of Life—an image the magazine claims “changed the face of AIDS.” As in “Golden Gate Park,” Rancourt interrupts the poem’s descriptive thread; this time, with quiet self-admonishment that arrives via the speaker’s admission that “Once I wanted / to be a martyr.” Surrounded by family saying their final goodbyes, the photo’s subject, David Kirby, serves as the speaker’s double, his would-be counterpart, the ghost of an imagined fate had the speaker been born decades earlier and contracted HIV. As Rancourt describes the final seconds of Kirby’s life, likening the scene to an “Ohio / pietà,” the writing again turns toward irony and paradox. “I can nearly see,” muses an omniscient Rancourt,

As in “Kirby,” Broken Spectre is very much about looking and looking back: of seeing oneself within the context of a wider history. It is a book less about the particularities of place than the hard-won perspective and recognition that “Time is elastic.” As Rancourt ultimately concedes, whether “it’s 1994, or it’s 1980, / or it was just last night, / it makes no difference: somebody slips out / the back screen porch / of their parents’ home / for the last time, someone leaves behind / everything they know / about how this will end …” (“Near the End of the Century”). Brocken Spectre ends with a final vision as the newlyweds introduced the collection’s first poem now find themselves hiking a volcano in Haleakalā National Park. Reflecting on the struggles of coming out in the 90s—an era in which, for many people, gayness “meant either you killed yourself / or you died from AIDS”—the speaker concludes that “the world // will go on generously without us.” The poem, too, goes generously on: as time flashes forward, the couple shares a kiss in bed while, across the island, the next generation of young lovers enters into self- and sexual discovery “[a]s if none of this / ever happened” (emphasis mine). This, of course, encompasses all that’s come before: the long history of eros, as well as the private pleasures and sorrows experienced by the speaker throughout his lifetime. It’s important to note that the final sentence fragment of Brocken Spectre is an act of self-erasure—one that relegates the speaker-poet, and by extension, Jacques Rancourt, to the past. Now part of a larger history, both figures serve as guiding spirits for those future selves who, longing for connection and continuity, will one day look back in hopes of recognizing their likenesses in the shadows of those who came before.

II

Winner of the Agha Shahid Ali Prize in Poetry, Benjamin Gucciardi’s full-length debut, West Portal, takes its name from a tranquil San Francisco neighborhood known for its residential tree-hemmed streets and the Twin Peaks Tunnel. Yet the phrase, as Gucciardi points out in the book’s front matter, likewise describes an “entryway into the afterworld—the westward movement of the soul after the body dies, following the path of the setting sun.” While there are numerous losses throughout West Portal—polluted habitats, evictions, a bus crash, overdoses and drowning, a devastating account of a boy collapsed in a Sonoran crossing—none build more momentum lyrically or radiate such clarity as those poems that internalize the death and imagined afterlife of the poet’s sister. Because time, according to Gucciadi, is “indifferent” to mourning, West Portal’s concentrated act of rendering, of giving shape to the beloved deceased, becomes a means of pivoting against the finality insisted upon by the material world. Art, in other words, provides an alternate form of survival and continuity. As the speaker in “Rendering the Pose” contends, “… only some memories wither. / It’s Darwinian, what remains becomes the standard / against which life is measured—.”

As Gucciardi surveys the expansive wake of days before and after his sister’s passing, West Portal subtly teases out the tension between perception and reflection, and how what’s felt or remembered gets translated into art. Often, self-conflict and turmoil are curiously transformative. A teacher tries to reconcile his student’s self-portrait as both ghostly fisherman and the sketched-out fish whose mouth is pierced by the “sharp curve of the barb” as it swings from the “arc of the fishing line” along “the single inked stroke of the pole” (“Rendering the Pose”). In another entry, readers learn that, mid-war, the Russian painter Kandinsky “turned away from severity / towards a brighter palette. // The lavishness of purple / as Warsaw was reduced to rubble” (“Little Accents”). Of a goldfinch that disappears into a tree hollow, Gucciardi concludes, “That’s what poetry is […]”

The above stanzas come from “The Nest,” whose title visually invokes a made thing, an object of found materials constructed for incubation and respite. It’s worth noting that the poem’s goldfinch, a species known for its persistent joy, slips “through a hole” that Gucciardi characterizes as “no bigger // than my open mouth”—a comparison that aligns the speaker simultaneously with the tree as well as the bird into which it disappears and, later, hones its song. Although its primary impetus initially seems observational, “The Nest” abruptly shifts from the descriptive to declarative mode midway, revealing itself as ars poetica: one that insists that art isn’t what is noticed but what is intrinsically felt. According to the speaker, the golden bird’s presence alone, its physical beauty, isn’t poetry. Gucciardi instead privileges the unseen, the enigmatic, as suggested by the stray notes concealed within the trunk. “[I]nstinct” here is of the utmost importance, i.e., the finch’s / poet’s compulsion toward interiority. Rather than some outward display, it’s internalized and in-born feeling that drives the solitary bird to retreat; it is “darkness” that informs why it sings.

Like the goldfinch in “The Nest,” Gucciardi’s speakers often “disappear” into spaces where pathos can be contained and (re)composed. At times, loss is intellectualized; elsewhere, the poems reflect the strange disorientation following grief. “I thought my sister’s ashes / would feel like masa” Gucciardi recounts early in the collection, “Clumpy, maybe, but milled / free from her figure.” The assonance binding ashes and masa resonates with chilling effect when considering the words’ oppositional meanings: ash being a powdery residue often symbolizing penance or mortality; masa, a dough made from maize flour. Ash, of course, is the consequence of burning; masa is pressed or kneaded for consumption. Because the physical reality of his sibling’s death is too excruciating, in other words, the speaker likens her cremated remains to a substance that not only nourishes, but also comforts the body. This train of thought is quickly interrupted, however, when the poet “cup[s] a handful / to sow in the canyon” and encounters “two triangles of bone / intact among the powder.” Again unable to directly confront death’s evidence, Gucciardi imaginatively transforms what might have been vertebrae or “middle phalanx” into a series of objects linked to childhood memories: a blade, an arrowhead, sea glass, and, finally, “the sails of the toy ship / we captained in the tub.” It’s a devastatingly simple and surprising turn, one in which Gucciardi restages an intimate, albeit familiar, domestic scene: two young siblings at play mid-bath. “Masa,” of course, does what the speaker can’t: denies the fact of mortality while reversing time. Knowing that looking back risks sentimentality, however, the poet troubles the stanza’s waters as if to foreshadow the family’s vulnerability. Though the tone of what’s remembered is light, the poem’s final three lines concede the inevitability of disaster as the speaker frankly decrees that even within the confines of the tub “we summoned a squall / through which only fools / like us would sail.”

While early entries in Gucciardi’s collection recount his sister’s life and death in San Francisco, elsewhere in West Portal the poet resurrects his sibling via a series of poems-as-inquiries. Distributed throughout the book’s four sections, poems like “I Ask My Sister’s Ghost How Dying Is,” “I Ask My Sister’s Ghost How Her Days Are Now,” and “I Ask My Sister’s Ghost to Take Me with Her” lend the sister-figure agency, insight, humor, and willfulness. In “I Ask My Sister’s Ghost to Play a Game of Cribbage,” the pair sits down for a round of cards during which conversation turns to sex in the afterlife. “We’ve never spoken of the body, or its pleasures,” confesses the speaker, “and I don’t want to speak of them now.” But the younger sibling is no match. “It’s better than poetry […] / but worse than cheap whiskey,” asserts his sister, “Better than a royal flush, she smiles, laying her cards between us / but nothing like shooting the moon.” Staged in couplets, the poem is rich with intimacy: there’s the ritualized game between family members, the quietness of private conversation, how the subject of lovemaking leads the speaker to discover that the practice of mourning has groomed him to take pleasure in feeling “Death’s breath on my neck.” The irony here, of course, is that everything is projection: that the physical estrangement caused by death inadvertently breeds a newfound closeness between the brother and sister who, within the confines of the speaker’s imagination and structure of the poem, manage to merge “without touching.”

Reading “I Ask My Sister’s Ghost to Play a Game of Cribbage,” I’m reminded of “Elegy and Eros: Configuring Grief,” an essay in which poet David Baker contends that, on the subject of bereavement, the lyric has evolved to “resist the static.” According to Baker, rather than seek “the solace or council of a hierarchy of power-holders, whether religious, literary, or political, [American poets] are active participants in their own songs and become the subjects of their own elegiac impulses.” The point, here, is agency: rather than fixed monuments beside which the dispirited grieve, Baker cites the dynamism of those elegies in which the relationship between speaker and subject is made more complex as it “continues on, in the direction of the sun.” Such expansiveness resonates fully in West Portal’s final entry, “I Ask My Sister’s Ghost to Write Her Own Elegy,” as the speaker returns to the creek where his sibling “spent her last years / testing toxins for the state.” Although we’re told “The place is nothing special,” Gucciardi’s readers now recognize that, through the lens of grief, everywhere holds a potential portal to the afterworld. Deftly layered, the poem serves not only as a playbook for mourning—“Say my death was not an act of violence,” utters the sister in a statement that might be read as either supposition or imperative—but also a lament for natural habitats threatened by aquatic trash, micro-plastics, chemical pollution, and urbanization. Although the sister-figure in West Portal ultimately counts her death as an act of generosity, a loss in a world that’s already overtaxed, the book’s speaker not only sees her “in all he sees,” à la Tennyson, but also recognizes that the ghostly presence is equally worth pursuing—that, as in art, feeling takes a variety of sounds and shapes, that the river of grief can lead to a breathtaking new existence, “an entrance / to the cold, thrashing sea.”

III

The Curious Thing confronts not the mortal loss of Brocken Spectre or West Portal, but the weight of emotional estrangement, artistic longing, and the intricacies of self. As in her previous award-winning volumes, The Wilderness and Loveliest Grotesque, Sandra Lim demonstrates a sharp instinct for expressing the cold data of lived experience. “Many mornings, we drank our coffee without any pleasantries,” the speaker in “Bent Lyre” flatly recounts. “At the table, along an axis of real and imaginary numbers, you made / your notes. I loved how true the imaginary numbers could be.” Fitted to instruments, “bent lyres” hold sheet music at a distance in order to free the musician to make their cornets sing. Of course, the fact that Lim frames the scene via the poet’s harp is no accident. Rather than the idyllic symbol of lyric poetry, however, Lim’s lyre is imperfect (i.e. “bent”), its sonic twinning with the word liar a subtle irony given the poem’s interest in romantic and mathematical “truths.” In its mapping of a bygone relationship, several phrases from “Broken Lyre” stand out and reflect well the central concerns felt throughout Lim’s collection: an axis of the real, you made your notes, I loved, how true the imaginary. Emphasizing form and structure, concentrated study, pathos, and the act of making the mind’s work known, such language reveals those tensions crucial to Lim’s poems on desire, uncertainty, desertion, and emotional endurance as what’s remembered throughout The Curious Thing becomes a premise against which theories of feeling are put to the test.

The brocken spectre-like presence that preoccupies The Curious Thing is that of a double consciousness or divided self. “I haven’t yet found / a manner in which to get over / my inconsistencies,” writes Lim in “Portrait in Summer.” And in “That Are”: “… there was my body, inside of my soul. / It had different aspirations.” Lim opens her collection with “The Protagonists,” whose title transforms the speaker from lyric authority into a human composite; a nameless character, in other words, whose decisions propel the poem’s domestic plot. At its surface, “The Protagonists” recounts the frustrations of failed romance. “At one time, / I asked for everything—//,” its first couplet begins, “When I saw how my love was squandered, / I would secrete venom.” In an effort to revitalize the relationship, the protagonist-speaker undergoes a radical transformation, opting to shed her snake-like self to play the part of happy songbird. “But now I sing of the fat, sleepy / little censor / who has replaced me,” she confesses in the third stanza, “whose disappointments // create the life of the house.” It’s a sly revision: Lim’s substitution of the cliché “fat and happy” with “fat, sleepy”—a shift that not only characterizes the people-pleasing “little censor” as depleted, but one that subtly suggests that she’s been deprived of her former joy. The “censor,” of course, is a self housed within the self, a characterization that splits the speaker in two. There’s the scorned lover who expresses anger in the poem’s early couplets versus the internalized “replacement” who conceals her suffering in order to save the relationship. Can the authentic and constructed self be reconciled? And what of the couple in crisis?

It’s easy to read “The Protagonists” as a portrait of romantic disillusionment. While the poem certainly succeeds in this capacity, it’s far more interesting in its nuanced scrutiny of selfhood and the way Lim holds a mirror up to the intimate “I” in order to expose the slippery slope between the healthy give-and-take of partnership and the hazards of self–compromise. Because of the speaker’s early mistreatment, it’s equally tempting to cast her partner as villain: an unworthy love interest for whom she sacrifices her own needs in order to “convey the supreme gaiety / of the heart.” As “The Protagonists” moves forward, however, the speaker’s initial neglect seems less injurious than her own abandonment of self. “What does the human heart love?” asks “The Protagonists,” to which the poem quickly answers, “To go, to have so far to go, // in deepest night!” Here, Lim’s emphatic iambs—To gó, | to háve | so fár | to gó | // in deép | est níght!—bring the lengths the heart travels into arresting clarity. As if at a cliff’s edge, the twice-repeated “go” lingers at the line’s end before plummeting into the next stanza’s “deepest night!” Although “the heart” is clearly in danger, what choice does the speaker have, the poem implies, but to trudge forward with her expected song? From this point, “The Protagonists” maps its greatest “challenge”; that is, the speaker’s need to secure her counterpart’s affections by projecting a certain joie de vivre. Such play-acting isn’t without consequence, however. In the end, the speaker weaponizes the unspoken resentments that harden within her. “[I]t is a stone,” concludes Lim of false happiness, “flung from a volcano.”

It’s no accident that The Curious Thing begins with the “protagonists,” a tool of composition, as the book both scrutinizes and pays homage to the written art. Authors Jean Rhys, Goethe, and Flaubert make cameos, as does Dutch philosopher Baruch Spinoza; there are nods to Jane Eyre and the pastoral, jabs about “lazy” metaphors, “A Shaggy Dog Story.” Sensual and unapologetically matter-of-fact, “Classics” revisits Ovid’s Metamorphoses by staging the speaker and her lover as a modern-day Diana and Actaeon in a gripping scene that plays out in a bar. Throughout The Curious Thing, language and literature bring pleasure and uncertainty. In “Portrait in Summer,” an academic on holiday “read[s] another psychosexual story / set in a dreary seaside town,” while the adult child in “Something Means Everything” acknowledges that “You don’t know what your story is about / when you begin it.” As the collection progresses, it becomes clear that The Curious Thing is as much about creative and intellectual longing as eros. In “Black Box,” one friend listens “in a small, grim café” while the other describes a recent break-up. “It was the kind of story I like,” confides the speaker, “and I wanted / to get it right, for later.” This concentrated act of listening and the archiving of detail again points to Lim’s engagement with duality. Even as she casts herself as sympathetic advocate (“My heart is always with the lovers”), the speaker is of two minds: part faithful witness, part thinking poet. Like the titular “Black Box,” a recording apparatus used to analyze data following a disaster, the speaker silently notes the register of her friend’s “voice like something brought up intact / from the cold center of a lake.” But is it possible to capture more than material particulars?, the poem seems to ask. What fear, despair, desperation does a black box miss? And by extension, what unspeakable feelings or thoughts dwell beyond the machinery of the writer’s imagination?

Whatever the lyric’s limitations, The Curious Thing remains committed to the art. In “The Absolutist,” which revisits family history, Lim recounts life in Seoul where her grandmother owned “an average, yet busy lunchtime canteen near the center / of the city.” The poem’s upper half is driven by labor as the woman fields deliveries, scrubs tables, is assaulted by the stink of garbage. Seven lines into “The Absolutist,” however, the grandmother takes up with “a careless married man.” This turn marks a significant tonal shift as Lim abandons sentences with surefooted leads (My grandmother ran, I can see, She always emerges, [She] walks home) for phrases that convey uncertainty (No one can tell me, I’d like to think, She was said to be, I tend to believe, maybe she was). Though Lim works hard to fill the gaps between the fragmented tales she’s inherited versus her grandmother’s lived experience, much of the woman remains unknowable: “In every photo she turns away from the camera; cover anyone’s face / and changed circumstances take up the burden of narrative.” The narrative “burden” here, of course, is that no chronicle is ever complete, no matter how fully imagined. Yet, as “The Absolutist” proves, even partial or subjective stories are worth telling as they reinvigorate the conditions of existence. Or, as Frank Bidart posits in Desire, “We fill pre-existing forms, and when / we fill them, change them and are changed.”

Although the speaker of “The Mountaintop” declares that “There is more to life than writing,” it seems that, in The Curious Thing, the pull of storytelling, its imbrication of idea, desire, and selfhood, is never exhausted. Throughout the collection, Lim continues to isolate ordinary moments with compelling lucidity using economical, tempered diction. Inward and self-aware, the poems in The Curious Thing look across distances of memory to consider the wonder of art- and self-making. “Part of me watches the rest of me being / anxious, superior, and invaded / by longing,” acknowledges one speaker, who goes on to concede “… There was / no deeper meaning” (“Chanson Douche”). But aren’t there times when feeling trumps meaning? Some losses that have no chance at being resolved? As Tennyson suggests by way of the self-apparition in In Memoriam A. H. H. (“He finds on misty mountain-ground / His own vast shadow glory-crown’d / He sees himself in all he sees”), songs of grief and of absence are often one-sided but no less beautiful, however skewed their vantages. Because, in the cases of Rancourt, Gucciardi, and Lim, the relationship between presence and counter-presence remains irresolvable, loss ultimately proves generative. Although the speakers who populate Brocken Spectre, West Portal, and The Curious Thing are, at times, bewildered, awe-struck, love-sick, or overwhelmed, there’s an openness about the work; a sense of fresh perspective that seems likely to transcend the collections’ final pages. Or, as Lim charges in a poem of just six lines:

Shara Lessley is editor-at-large and a frequent reviewer for West Branch. She edits “This Long Winding Line,” our regular retrospective on noteworthy poetry books. She is the author of two books of poetry, Two-Headed Nightingale and The Explosive Expert’s Wife.