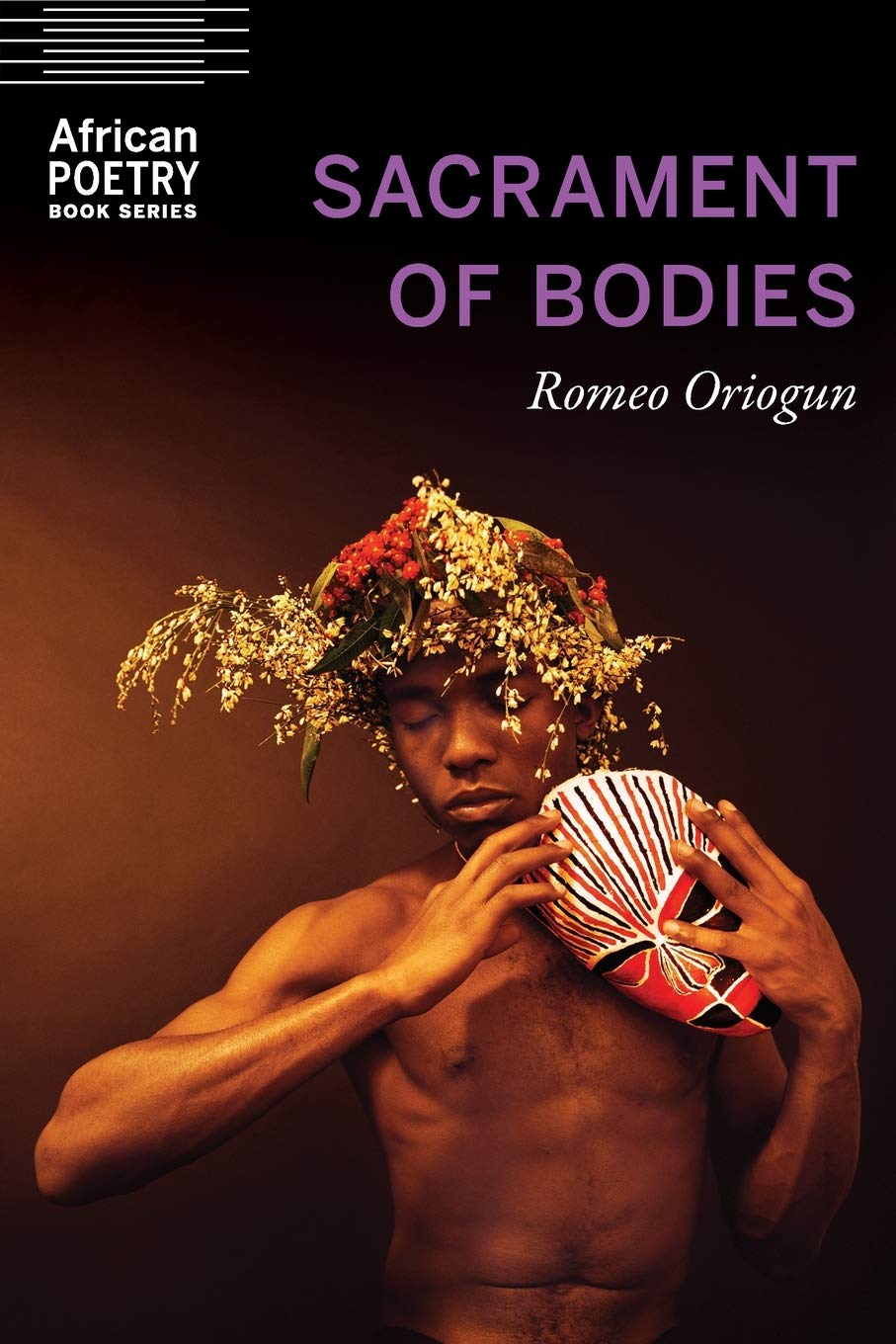

Sacrament of Bodies, by Romeo Oriogun. University of Nebraska Press, 78 pp., $17.95.

It doesn’t take a reader long to be captured by Romeo Oriogun’s compelling voice, a voice which seems equal parts observer, prophet, and reformer—a voice possessing the strength to rejoice amid trauma or to create visions of any ruling tyrannical force as if it were glass, to be seen through or reflected. In his debut collection, Sacrament of Bodies, Oriogun works to draw the reader’s attention, often with visceral detail, to the violences related to colonization and misogyny in his home of Nigeria. Oriogun’s speaks against the oppressive remnants of dogma and authoritarianism. One of the primary intentions of this collection is to show. Once again, the connection between power and oppression, to cast visions of how dogma and ideology make their way into the thoughts and actions of individuals through the policing of bodies. One of the most endearing aspects of this collectionis the poet’s resolution to create spaces of new representation by crafting poems that sing with great joy and reverence amidst ongoing injustice.

In the second poem of the collection, “The Ritual of Giving a Body Its Name,” Oriogun asks the question: “Who are we to give hunger a name?” Thus, the poet begins to explore structures of power that influence naming and identity. Hunger is often a metaphor to introduce the reader to Oriogun’s larger topic, desire. Sacrament of Bodies offers the reader a deep dive into the needs of the body and the needs brought on by desire. The desire in these poems changes contextually; sometimes it is sexual, sometimes physical, and very often it is melded with the pursuit of liberation. By asking his question so early on, the poet tactfully leads the reader through structures of inequality founded upon acts of misogyny and violence.

In “Prelude to Freedom” Oriogun writes:

Oriogun often draws an intersecting line between family and popular belief, between history and conviction. We journey through the speaker’s understanding of their identity and the way it has been visualized in the world, physically manifested in images of men enjoying the pleasures of their own bodies as well as each other’s, sometimes in the midst of dance, sometimes in deep passion for one another, and sometimes, most hauntingly, set ablaze.

In “How to Survive the Fire” Oriogun writes

As the poems progress, we move from the family to the community and then further. We see lasting reminders of a disorderly and toxic masculinity in the violences that befall members of the LGBTQ+ community. Sacrament of Bodies finds the poet wrestling with the language necessary to interrogate this history of violence while repurposing his own memory that has been influenced by terror. Oriogun offers a glance at this oppression and a hope of speaking new life into an already failing system. Oriogun’s imaginative recreation of these spaces explores sexuality and masculinity in necessary ways.

These poems are songs of protest, but they are also often songs of joy. Oriogun, who has gained attention due to his association with a “new African poetry” movement, offers a new perspective on the intentions of representation. Rather than representation being a remedy for past injustices, here, representation indicts injustice for what it has meant and draws the attention to whom a lack has belittled and harmed. In the poem “Departure,” Oriogun writes, “Every day men hurting bodies filled with love / are praised as heroes, / are hailed as saviors opening bodies / into fields eaten by locusts.” Here and elsewhere the poet is concerned with misogyny’s whims and its lasting impact. Misogyny would rather silence through terror than allow for desire to live freely, and in Oriogun’s detailed recollections, we see this happen time and again. This poetry seeks to preserve the body against such violences, making it something holy to be revered.

Oriogun’s works is a rebellion seeped in the joy of expression. What this poet offers is a way to return the gaze of these oppressive forces, and an understanding that to overcome such dogma means not playing on their terms. Primaily written in single stanzas of free verse, the poems show the influence of poets like Chris Abani and Natasha Tretheway. Oriogun does not only speak the realities of shame or silence; he writes poems that sound like prayers of hope, as if to say, there are no unholy bodies that lack access to redemption, there are no institutions above interrogation. There is only what we know and what we can build, first by observing our past and validating our experiences of pain.

Jordan Charlton is a PhD student in English at the University of Nebraska. He works with the Nebraska Writers Collective, working with both high school youth poets and incarcerated writers through the programs Louder Than a Bomb and Writers’ Block.