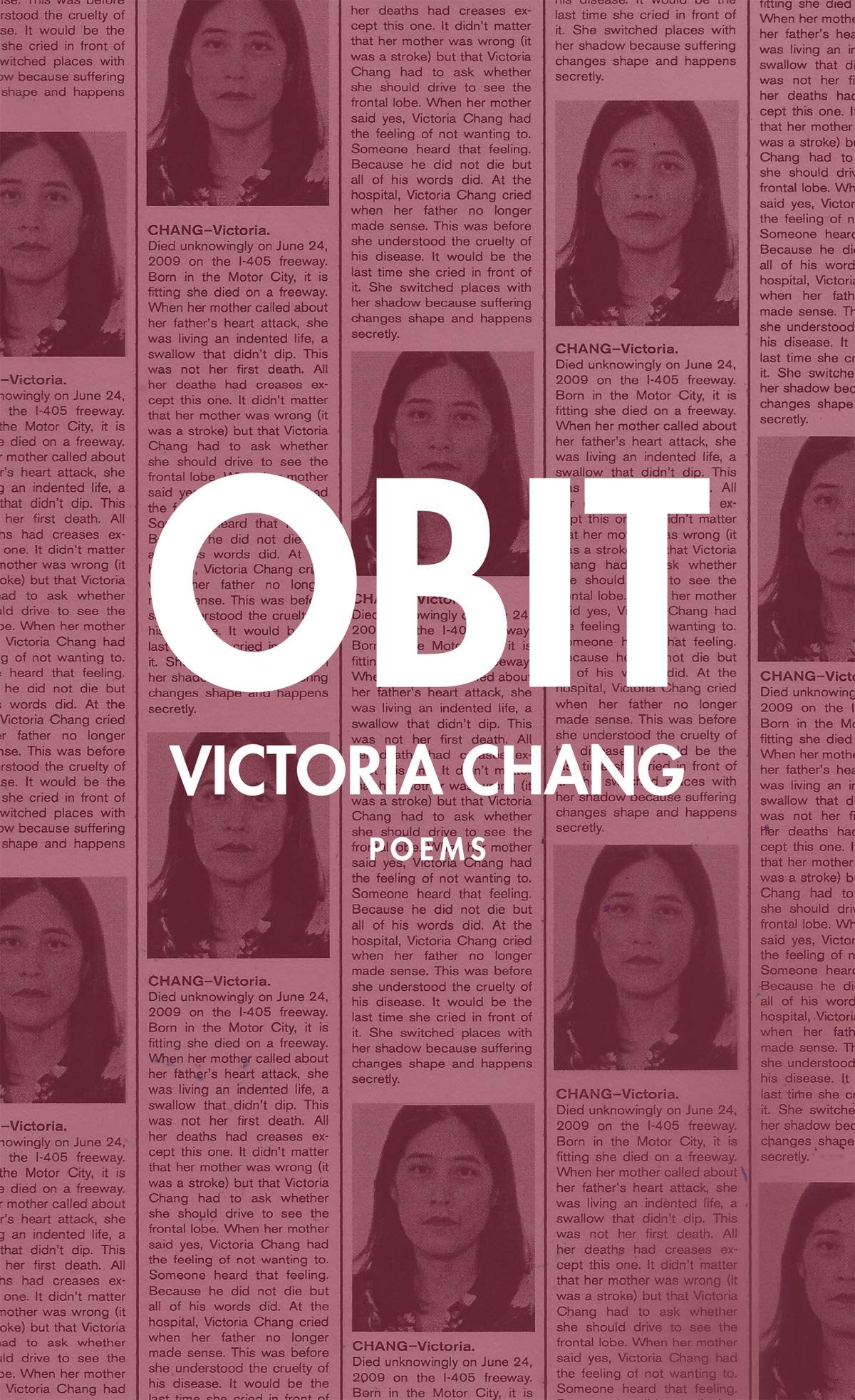

OBIT, by Victoria Chang. Copper Canyon Press, 120 pp., $17

In her newest poetry collection, OBIT, Victoria Chang quotes John Updike, who wrote, “Each day, we wake slightly altered, and the person we were yesterday is dead. So why, one could say, be afraid of death, when death comes all the time?” She immediately counters him: “Updike must not have watched someone slowly suffocating.” OBIT, Chang’s litanaic barrage of elegies responding, primarily, to a mother’s death and a father’s stroke, is able to contain both of these impulses. In its form—a series of obituaries on everything from “My Father’s Frontal Lobe” to “Friendships” to “America”—it asserts that loss, in its pervasiveness or its persistence, could become pedestrian, something we go through constantly. At the same time, the poems contained in this collection document the always-new pain that we experience as we grieve. In “The Blue Dress,” for instance, Chang wonders,

whether they burned [her] dress or just the body? I wonder who lifted her up into the fire? I wonder if her hair brushed his cheek before it grew into a bonfire? I wonder what sound the body made as it burned?

One hundred losses are contained in that one loss of a mother and Chang attempts to render each in its eviscerating reality, highlighting the mind-numbing expanse of grief, certainly, but also the raw core that expanse keeps asking you to touch. Grief, in its persistence, becomes pedestrian—even as it maintains its throb. Chang’s grief evolves and circles back on itself in the course of OBIT, as each obituary helps us understand a new shade of her speaker’s pain. In “Similes,” Chang writes “there was nothing like death, just death. Nothing like grief, just grief. How the shadow of a chain-link fence can look like a fish’s scales but never be.” In OBIT, death is necessarily everywhere and is an entirely singular experience. In the face of it, the speaker has to admit that language, the thing she—and we—use to process it, and that currently takes the form of these obituaries, is inadequate. She can represent what she’s feeling, but the difference between the representation and the experience is as stark as the difference between the scales of a fish and the shadow of a chain-link fence. Words fail her—but she can’t help but follow her compulsion toward them.

Language and its failures are one of this speaker’s obsessions.

Language and its failures are one of this speaker’s obsessions. Her grief stops her mouth, but her father also loses the ability to speak after his stroke. In the collection’s first poem, “My Father’s Frontal Lobe,” the obituary tells us that,

My Father’s Frontal Lobe—died unpeacefully of a stroke on June 24, 2009 at Scripps Memorial Hospital in San Diego, California … The frontal lobe loved being the boss. It tried to talk again but someone put a bag over it. When the frontal lobe died, it sucked in its lips like a window pulled shut. At the funeral for his words, my father wouldn’t stop talking and his love passed through me, fell onto the ground that wasn’t there.

The loss of the father’s words becomes a loss of the father, a loss of his love, which passes through the speaker’s body without touching her, like she’s a ghost. Without words to describe the experience, it moves through and away from her—she isn’t able to contain it. “I could hear someone stomping their feet,” she goes on. “The body is as confusing as language—was the frontal lobe having a tantrum or dancing … I understood then that darkness is falling without an end. That darkness is not the absorption of color but the absorption of language.” She and her father are plunged into the dark, where meanings are obfuscated or missing entirely. Chang gropes for these meanings in the dark of grief.

The dark Chang’s speaker finds herself in is the dark of formlessness. “Form—,” she writes, “died on August 3, 2015. My children sleep with framed photos of my mother. Leaden, angular, metal frames. My ten-year-old puts her frame in the red velvet bag that held the cremation urn and brings it with her on vacation.” The body, as a form, has been drastically altered after death, so much so that the relationships between the living and the dead are, in a way, perverse, strange, strained. How does one touch, come near to, the dead? The speaker’s child tries to keep her grandmother close to her, but the results are strange, a funeral urn on the beach. “When we die,” Chang goes on, “we are represented by representations of representations, often in different forms. Memories too are representations of the dead. I go through corridors looking for the original but can’t find her.” These representations are as much a barrier to accessing the mother as they are a connection to her. Our only real access to the dead—memory—is as flawed as our imaginations are. In the obituary for empathy, Chang writes,

I can never feel my mother’s illness or my father’s dementia. The black notes on the score are only representations of sound, the keys must knock certain strings which are made of steel, steel is made of iron and carbon from the earth. Why do we make things like a piano that try to represent beauty or pain? Why must we always draw what we see? Just copy it, my mother used to say about drawing. The artist is only visiting pain, imagining it. We praise the artist, not the apple, not the apple’s shadow which is murdered slowly. There must be some way of drawing a picture so that it doesn’t become an elegy.

Even in life, we are intractably isolated in our own experiences, and even as we try to imagine ourselves out of them, we—the writers, the artists—are the central focus of our own efforts. How could we access the dead using such flawed tools, Chang seems to ask. She writes later, in the poem “Language,”

When my mother was dying, I made everyone stand around the bed for what would be the last group photo. Some of us even smiled. Because dying lasts forever until it stops. Someone said, Take a few. Someone said, Say cheese. Someone said, Thank you. Language fails us. In the way that breaking an arm means an arm’s bone can break but the arm itself can’t break unless sawed or cut.

In these last moments of the mother’s life, there is no way to accurately describe their situation, no way to accurately commit the moment to memory. Instead, the living settle for what they have. Words can’t capture this in-between space, the difference between the expression “breaking an arm” and the reality of that phrase. In the face of the grief Chang is describing, the inexactitude of the living is nearly callous. The artist takes pictures of the last moments of the dying or the artist writes poems after those last moments—but neither give the artist any more access to the interiority of that dying person—and the reader experiences the echo of an echo, as Chang asserts in “Blame:” “When some people suffer they want to tell everyone about their suffering. When the brush hits the knot, the child cries out loud, makes a noise that is an expression of pain but not the pain itself. I can’t feel the child’s pain but some echo of her pain, based on my imagination.”

Though Chang seems to assert that the pain of others is distant from her, that her own pain is distant from us, the readers, the way she carefully, hauntingly renders her grief is a counterargument itself. In “The Head,” Chang tells us how her mother’s body was taken away:

When the two men finally came, they rolled a gurney into the other room, hushed talking and noises, then the tip of the gurney came out like a cruise ship. They were worried about dinging the walls. My mother’s whole body covered with a blanket. Her head gone. Her face gone. Rilke was wrong. The body is nothing without the head. My mother, now covered, was no longer my mother. A covered apple is no longer an apple. A sketch of a person isn’t the person. Somewhere, in the morning, my mother had become the sketch. And I would spend the rest of my life trying to shade her back in.

The obsessive qualities of this collection are reflected here. These poems, so recursively focused on the moments of the speaker’s grief, go against the portrait of the artist as a detached observer. Instead, the artist’s inability to render the grief, the dead beloved, as they are, is a suffering itself. Is a death itself. “Victoria Chang—died on August 3, 2015,” one poem asserts. “Victoria Chang—died unknowingly on June 24, 2009 on the I-405 freeway,” says another. “Victoria Chang—died unwillingly on April 21, 2017 on a cool day in Seal Beach, California,” says another still. She who was “the one who never used to weep when other people’s parents died” is dead: “Now I ask questions, I bring glasses. I shake the trees in my dreams so I can tremble with others tomorrow.” It is the speaker’s attempts to “shade her [mother] back in” that change her, that kill her old self. Her struggle against the unsayability of her own pain can’t give her better access to her mother—but this restless turning over does open her to others. As the last poem in the collection, a tanka, says, “My children, children/this poem will not end because/I am trying to end this poem with hope hope hope/see how the mouth stays open?”

This book doesn’t want to end, doesn’t want to close the space in which these lives still exist. After all, at the end of grief, where does the beloved go? “Grief—as I knew it, died many times,” Chang asserts. “It died trying to reunite with other lesser deaths. Each morning I lay out my children’s clothing to cover their grief. The grief remains but is changed by what it is covered with.” In a collection like OBIT, where the speaker’s grief shifts between foci—it’s the mother who’s died and whom the poet grieves, but also the poet herself, home, empathy, language—this image of grief is apt. The loss of the mother becomes the loss of everything, of even the structures that the poet used to understand her life and relationships before, of even the structures the poet wants to use to process the pain she’s experiencing, of even the poet’s sense of who she is, always defined in relationship to, in the context of. Can a grief like that end, OBIT seems to ask? “She was mine, all mine,” Chang writes at the end of the last “Victoria Chang” obituary. “Therefore anger toward her was mine. All mine. Anger after someone has died is a cake on a table, fully risen. A knife housed in glass.” The grief here is as quiet and complete as that cake, as untouchably there, as static as “a knife housed in glass.” The poet must try to render it again.

Katie Berta is the managing editor of The Iowa Review. You can find her book reviews in American Poetry Review, Ploughshares, and Harvard Review, among other magazines. Her poems appear widely in journals. She has a PhD in poetry from Ohio University.